Stamp collecting, often associated with philately (or the study of stamps), is a hobby that has been around since the first postage stamp was issued by Britain in May of 1840. Since then, stamp collecting has been one of the world’s most popular hobbies, resulting in the production of over 400,000 different types of stamp by the year 2000.

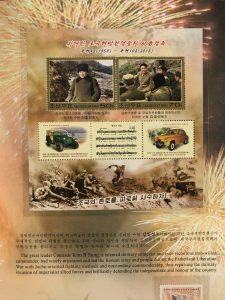

Many of the stamps produced are from smaller countries seeking to bring in much needed revenue, which they achieve through the printing of limited run stamps specifically for stamp collectors. One such country happens to be North Korea. This fact came to my attention when a collection of North Korean stamp albums arrived at our lab.

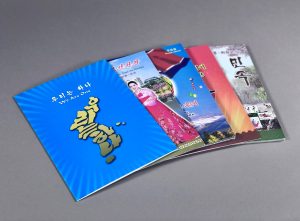

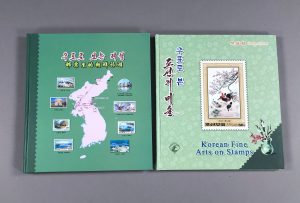

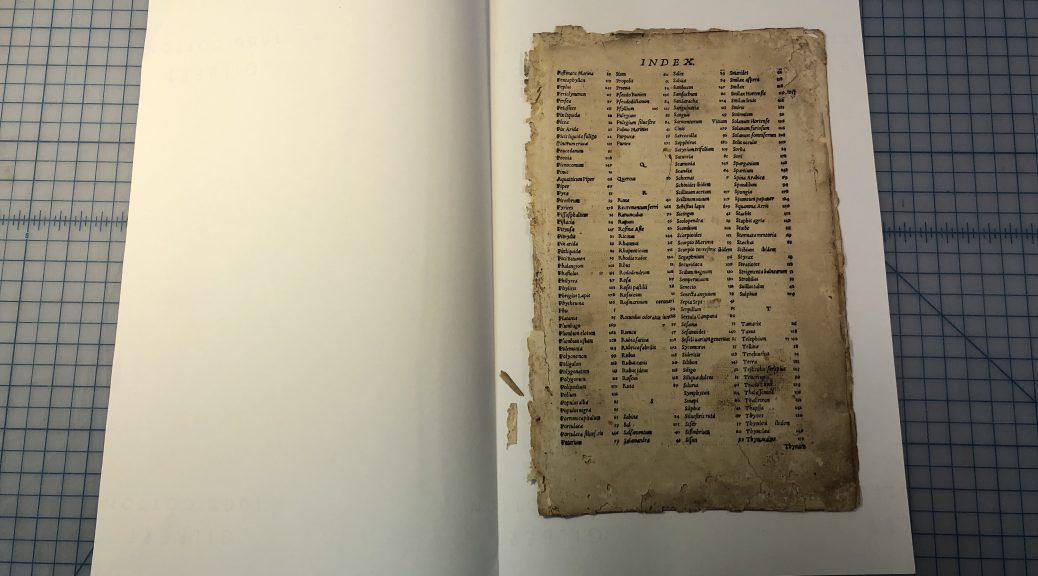

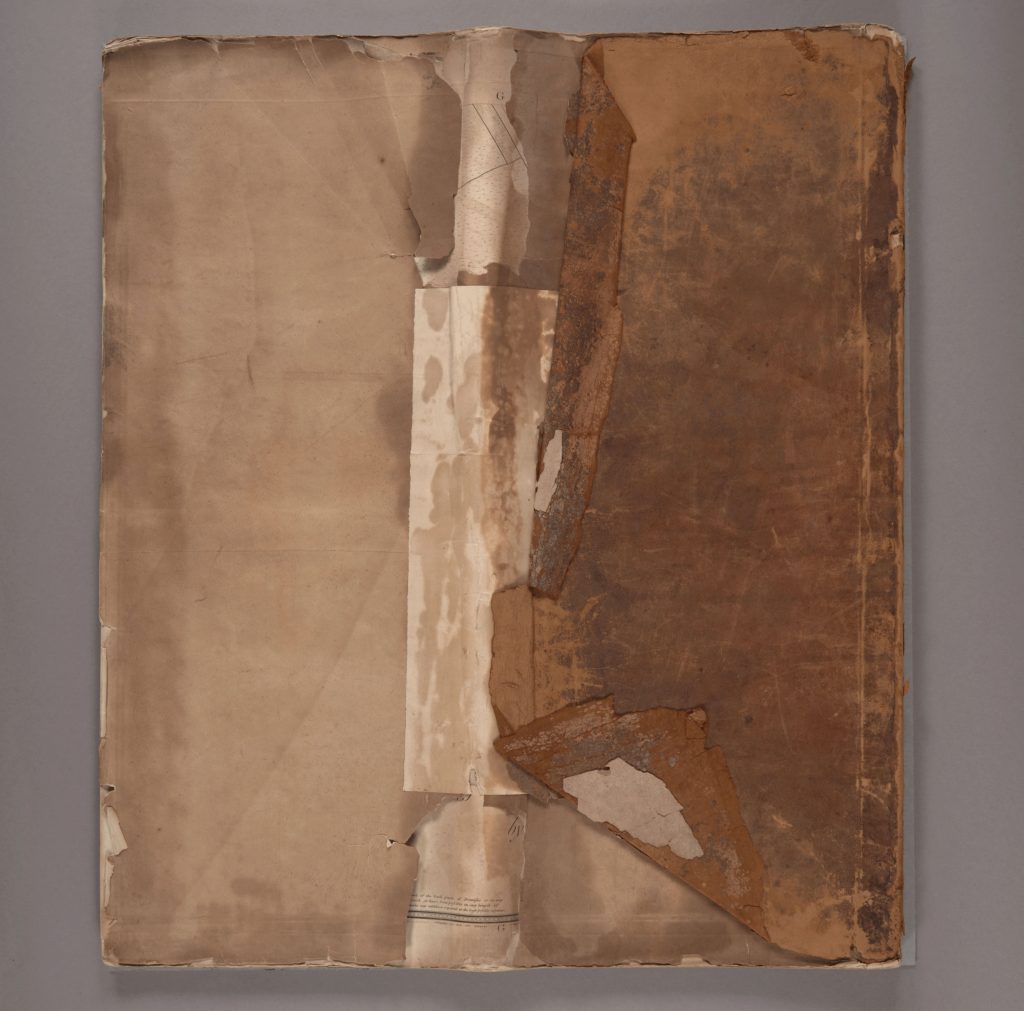

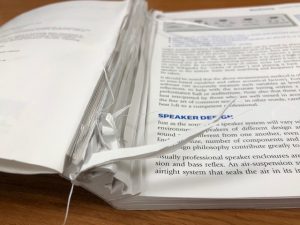

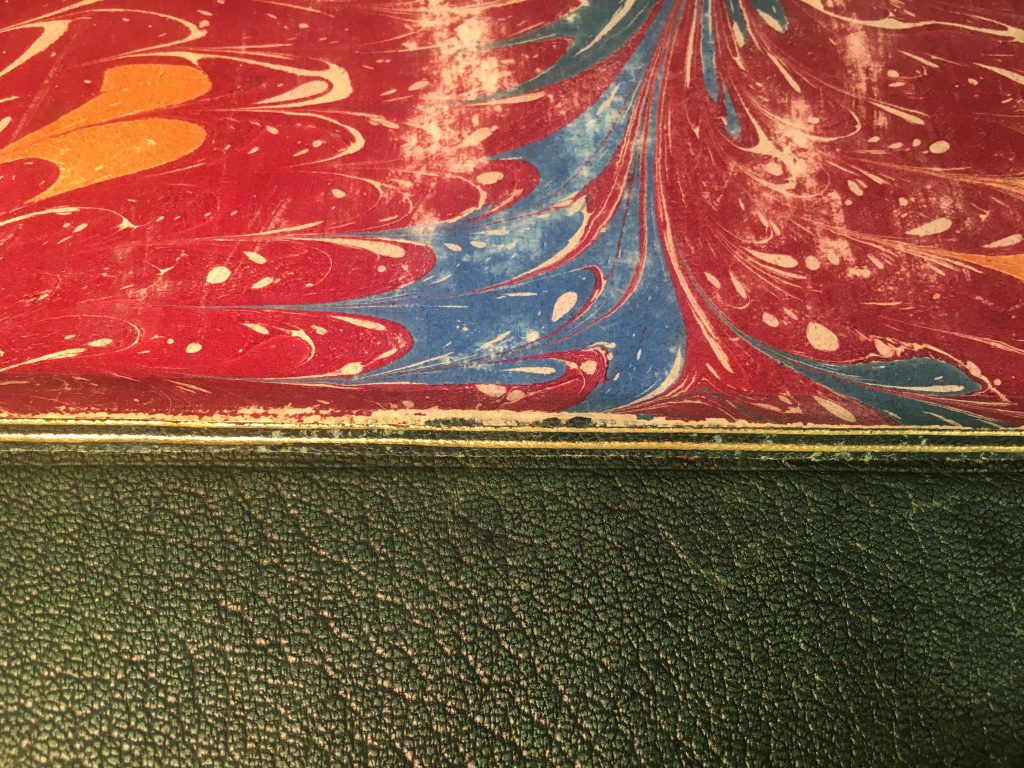

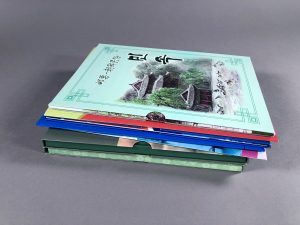

The collection consists of five stapled pamphlets and two bound books, all full of loose stamps in need of securing.

The collection consists of five stapled pamphlets and two bound books, all full of loose stamps in need of securing.

I will mention that it is unclear whether these are actually functional stamps or just coated paper made to look like stamps. There is no noticeable adhesive on the backs of them, and even a UV light analysis and our ordering specialist couldn’t get us any closer to a conclusive answer.

Regardless, we couldn’t risk all of these stamps being lost or stolen. I had to find a way to contain them all so that patrons could access these albums without leaving the fate of these stamps to chance.

How do we treat these items?

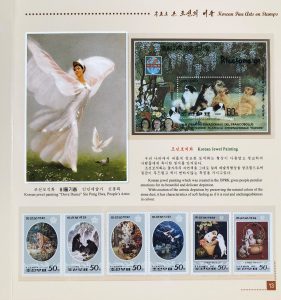

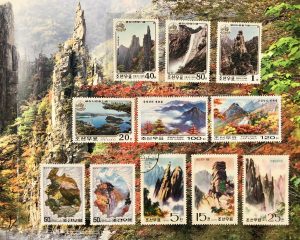

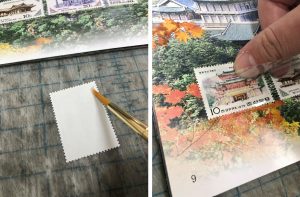

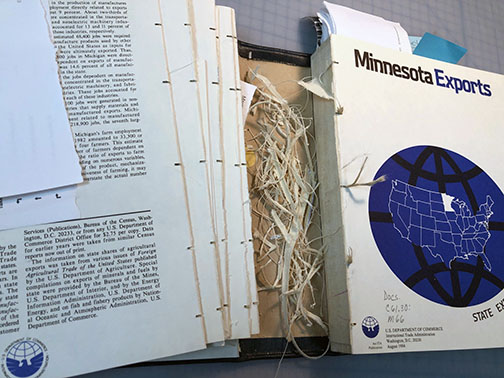

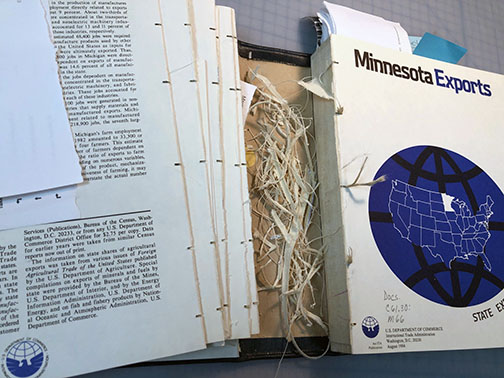

Each of these albums is made up of pages containing several small slips of mylar with the bottom edge adhered to the actual page.

Within each of these slips sits either a single stamp or multiple stamps, which varies from page to page.

Although the stamps don’t necessarily fly about or out of the slips as you flip through the pages, it’s obvious that they aren’t exactly going to just stay in place over time.

So, what is the solution here?

Since these mylar slips were already at my disposal, it made the most sense to use them to my advantage. After applying a thin bead of wheat starch paste to the top of each stamp, I tipped each stamp into the mylar and made sure the bottom of the stamp was placed as far down into the slip as possible.

This way the stamp is secured in place without having to glue up the entire back of the item, and the mylar acts as a catch for the bottom of the stamp so that they can’t be pulled out as easily. With the stamps now safely secured, these albums are ready for a closer look at their contents.

How do we interpret these items?

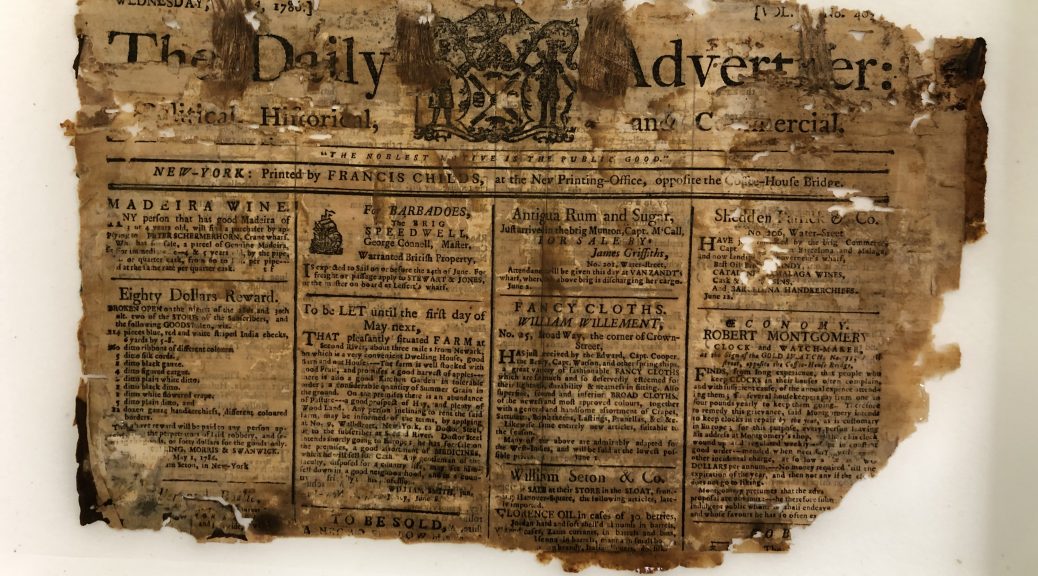

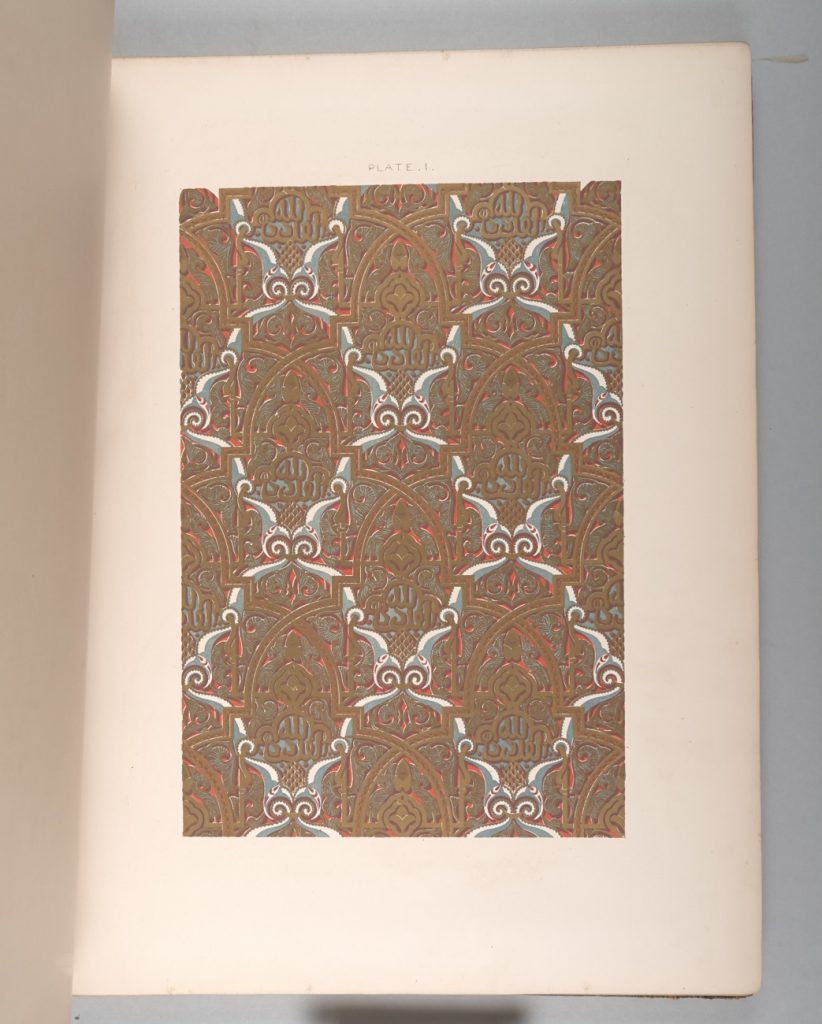

These albums seem to be geared towards foreigners and tourists. Of the seven albums here, three contain text in Korean, Chinese, and English, one contains text in just Korean and English, and the other three contain text in just Korean and Chinese. Seeing as none of these are written only in Korean, it can be assumed that these albums were not intended solely for Korean audiences.

As you have also probably noticed, these stamps cover a wide variety of subjects as well. It seems as though you can find a stamp on just about anything if you really wanted to. This is probably for the benefit of appealing to as many collectors as possible who might only collect certain kinds of stamps.

The world of stamps is quite intriguing, especially considering how they can become vehicles for propaganda. Are you a stamp collector or a philatelist (someone who studies stamps)? Leave a comment with your thoughts on this collection if you are, and leave a comment even if you aren’t! We’d love to hear what you think about our new addition to the Perkins Library. If you’d like to find these items in our catalog, you can click any of these links.