There’s something special about a book made with handmade paper. You don’t come across it too often in general collections, but, when you do, you want to take extra good care of it. This week a beautiful example of this arrived at the lab in the form of The Poems of Sappho, printed in 1910. As you can see in the images below, the book was in rather rough shape. I could tell it would be the perfect candidate for a new case. This means I would need to make new covers for this book.

Upon opening it, I immediately noticed the lovely deckled edges of the paper and what appeared to be a watermark.

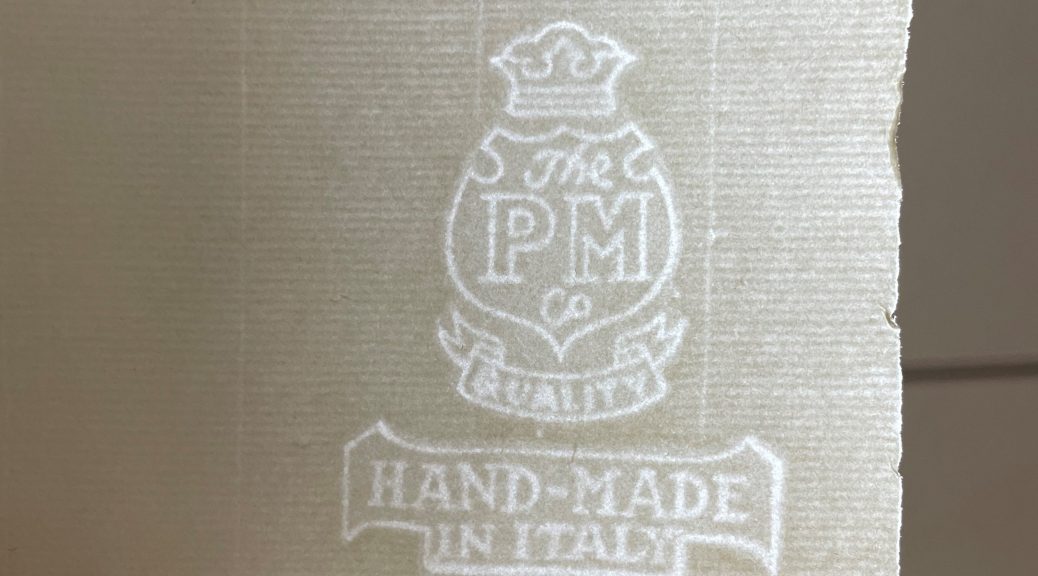

A watermark is an image or design that is impressed into the paper during the papermaking process. This is easier to see when you hold the paper up to a light like so.

The main purpose of a watermark is to identify the papermaker; however, this watermark goes even further and tells us where the paper was made as well. In this case, the paper was handmade in Italy by a group called “The PM co”, which could possibly refer to The Paper Mills Company.

Saving this paper and the vital information on it is going to be my priority as I treat this book. This should be relatively straightforward, but what happens when two of these pages have been glued to the covers?

Preserving the Paper

When the book was bound, the pastedowns were made with the first and last sheet of the textblock of the book rather than using a separate decorative paper.

In order to make a new case for a book, I have to remove the old covers. I must lift the original handmade paper from the front and back boards to retain it. This can be done by taking an exceptionally thin metal spatula and running it back and forth under the paper to loosen and separate the paper from the covers.

This can be a tricky and time-consuming process if the paper is old and brittle, or if the paper is well adhered to the covers and doesn’t want to come off. Luckily, both pages cooperated with me and I managed to remove the covers without damaging the paper.

A lot of the original board material had to be lifted along with the paper, so the next step is to remove that material from the pages. Leaving it on would make it nearly impossible to neatly reattach the pastedowns when I made a new case for this book. So, I removed as much as I could mechanically before moving onto the rest of the treatment.

With the brand-new case complete, the book and it’s handmade paper are better protected and ready to be handled.