A recent tweet from my colleague in the Rubenstein Library (pictured above) pretty much sums up the last few weeks at work. Although I rarely work directly with students and classes, I am still impacted by the hustle and bustle in the library when classes are in session. Throughout the busy Spring I found myself saying, oh I’ll have time to work on that over the Summer. Now Summer is here, so it is time to make some progress on those delayed projects while keeping others moving forward. With that in mind here is your late Spring and early Summer round-up of Digital Collections news and updates.

Radio Haiti

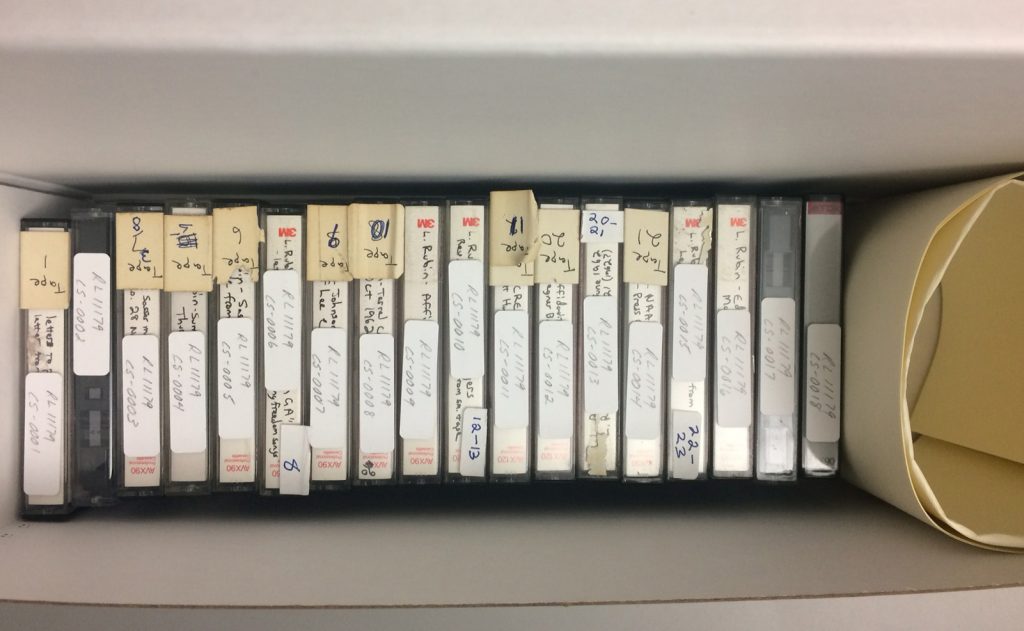

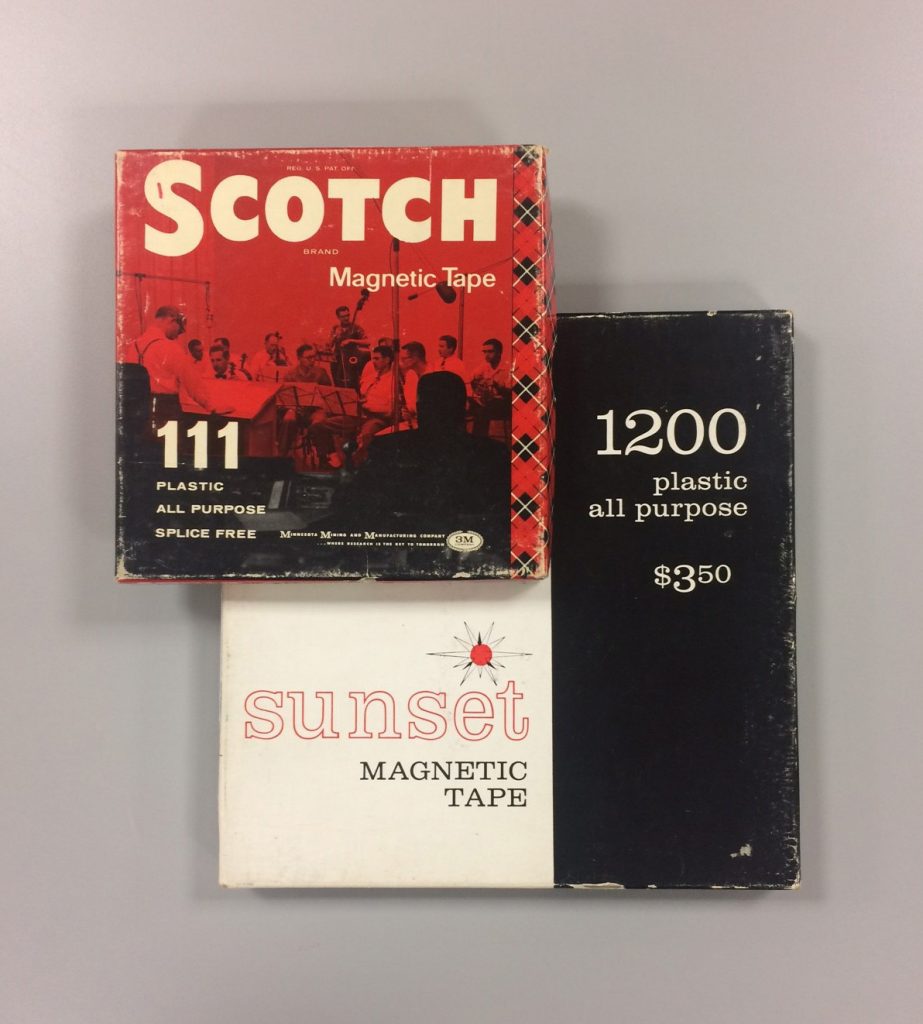

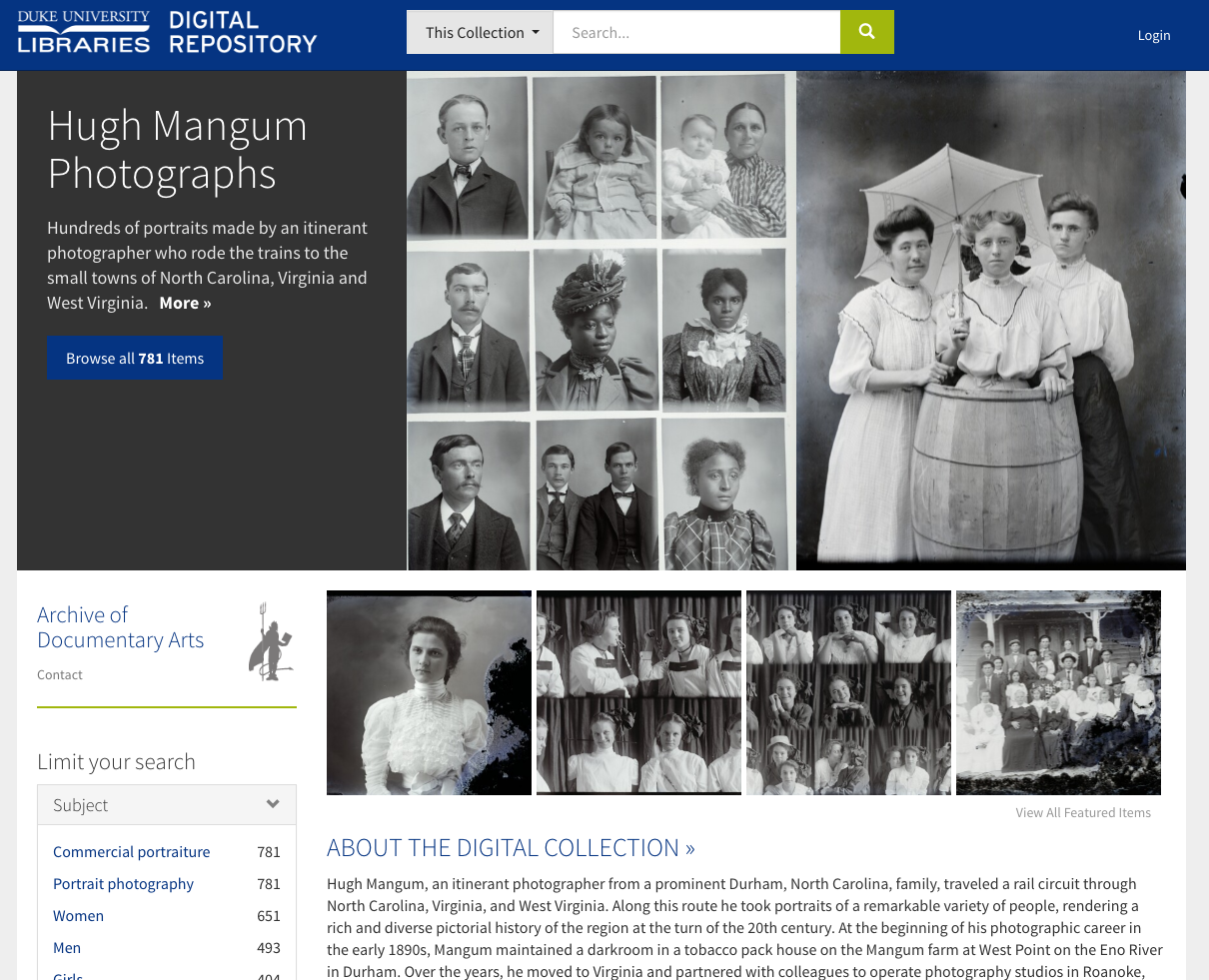

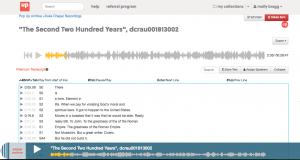

The long anticipated launch of the Radio Haiti Archives is upon us. After many meetings to review the metadata profile, discuss modeling relationships between recordings, and find a pragmatic approach to representing metadata in 3 languages all in the Duke Digital Repository public interface, we are now in preview mode, and it is thrilling. Behind the scenes, Radio Haiti represents a huge step forward in the Duke Digital Repository’s ability to store and play back audio and video files.

You can already listen to many recordings via the Radio Haiti collection guide, and we will share the digital collection with the world in late June or early July. In the meantime, check out this teaser image of the homepage.

Section A

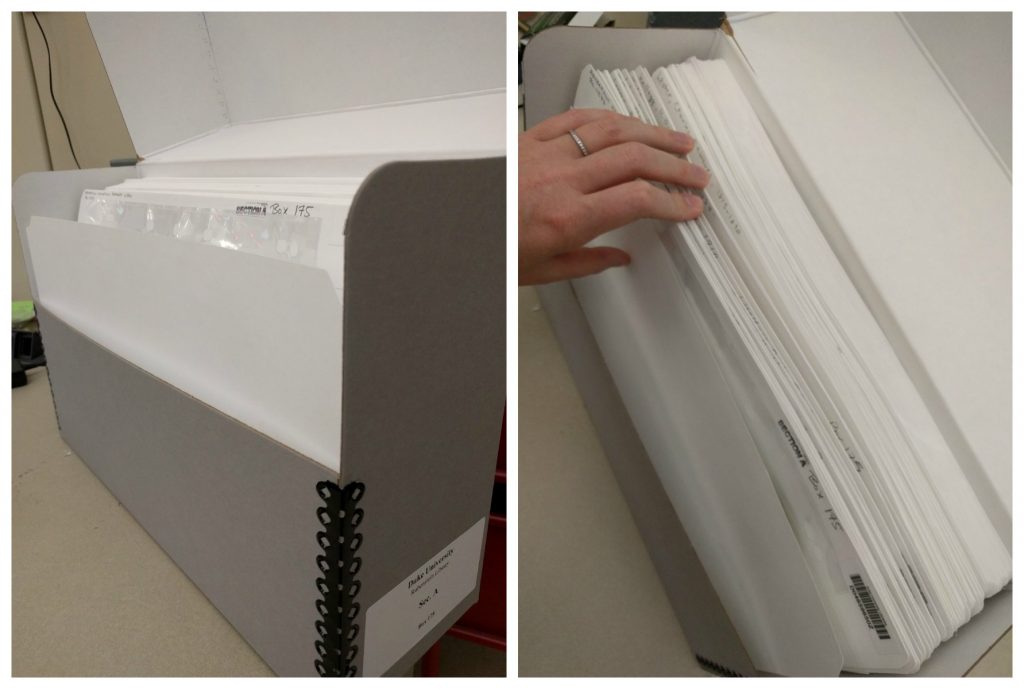

My colleague Meghan recently wrote about our ambitions Section A digitization project, which will result in creating finding aids for and digitizing 3000+ small manuscript collections from the Rubenstein library. This past week the 12 people involved in the project met to review our workflow. Although we are trying to take a mass digitization and streamlined approach to this project, there are still a lot of people and steps. For example, we spent about 20-30 minutes of our 90 minute meeting reviewing the various status codes we use on our giant Google spreadsheet and when to update them. I’ve also created a 6 page project plan that encompasses both a high and medium level view of the project. In addition to that document, each part of the process (appraisal, cataloging review, digitization, etc.) also has their own more detailed documentation. This project is going to last at least a few years, so taking the time to document every step is essential, as is agreeing on status codes and how to use them. It is a big process, but with every box the project gets a little easier.

Diversity and Inclusion Digitization Initiative Proposals and Easy Projects

As Bitstreams readers and DUL colleagues know, this year we instituted 2 new processes for proposing digitization projects. Our second digitization initiative deadline has just passed (it was June 15) and I will be working with the review committee to review new proposals as well as reevaluate 2 proposals from the first round in June and early July. I’m excited to say that we have already approved one project outright (Emma Goldman papers), and plan to announce more approved projects later this Summer.

We also codified “easy project” guidelines and have received several easy project proposals. It is still too soon to really assess this process, but so far the process is going well.

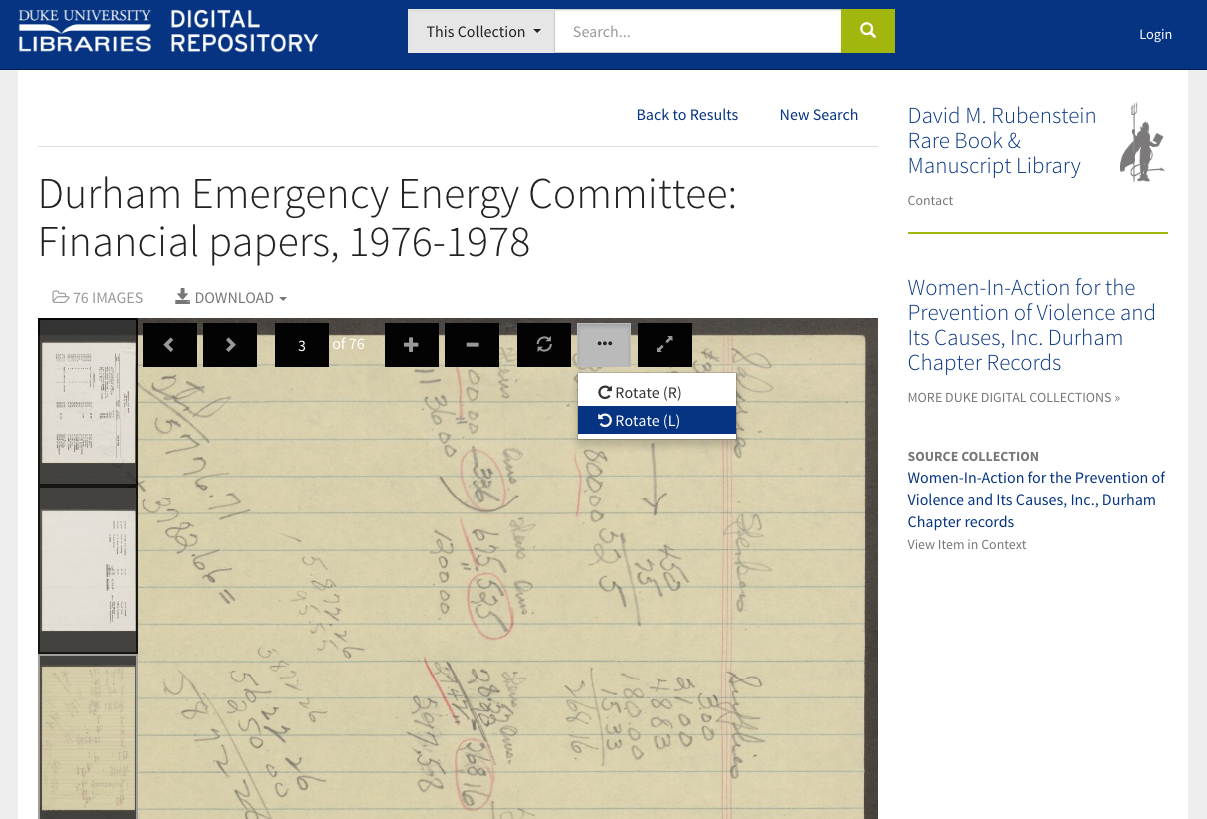

Transcription and Closed Captioning

Speaking of A/V developments, another large project planned for this Summer is to begin codifying our captioning and transcription practices. Duke Libraries has had a mandate to create transcriptions and closed captions for newly digitized A/V for over a year. In that time we have been working with vendors on selected projects. Our next steps will serve two fronts; on the programmatic side we need review the time and expense captioning efforts have incurred so far and see how we can scale our efforts to our backlog of publicly accessible A/V. On the technology side I’ve partnered with one of our amazing developers to sketch out a multi-phase plan for storing and providing access to captions and time-coded transcriptions accessible and searchable in our user interface. The first phase goes into development this Summer. All of these efforts will no doubt be the subject of a future blog post.

Summer of Documentation

My aspirational Summer project this year is to update digital collections project tracking documentation, review/consolidate/replace/trash existing digital collections documentation and work with the Digital Production Center to create a DPC manual. Admittedly writing and reviewing documentation is not the most exciting Summer plan, but with so many projects and collaborators in the air, this documentation is essential to our productivity, communication practices, and my personal sanity.

Late Spring Collection launches and Migrations

Over the past few months we launched several new digital collections as well as completed the migration of a number of collections from our old platform into the Duke Digital Repository.

New Collections:

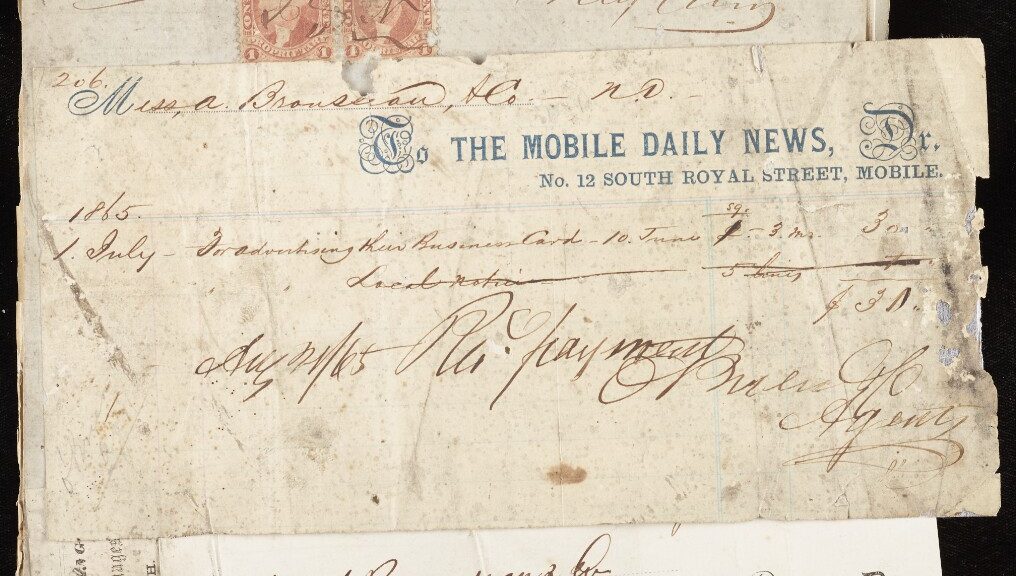

- A. Brouseau & Co. records: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/abrouseauco-002388080

- Abolitionist Speech: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/abolitionistspeech-001099688

- Frank Baker Collection of Wesleyana and British Methodism: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/frankbakercol

- Wesley Family papers: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/wesleyfamilypapers

- William Wilberforce papers: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/wilberf

- Samuel Wilberforce papers: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/wilberforcesamuel

Migrated Collections:

- Alexander H. Stephens Papers: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/ahstephens

- Classical String Quartets: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/quartets

- Duke Football Programs: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/dfp

- History of Medicine Artifacts: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/homartifacts

- Italian Cultural Posters: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/italianposters

- Manuscripts and Woodcuts: Visions and Designs from Bloomsbury: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/bloomsbury

- Marshall Meyer Papers: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/meyermarshall

- Musee des Horreurs: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/museedeshorreurs

- Paul Kwilecki Photographs: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/kwilecki

- Protestant Children and Families: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/protfam

- Ration Coupons on the Home Front: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/hfc

- Russian Posters Collection: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/russianposters

…And so Much More!

In addition to the projects above, we continue to make slow and steady progress on our MSI system, are exploring using the FFv1 format for preserving selected moving image collections, planning the next phase of the Digital Collections migration into the Duke Digital Repository, thinking deeply about collection level metadata and structured metadata, planning to launch newly digitized Gedney images, integrating digital objects in finding aids and more. No doubt some of these efforts will appear in subsequent Bitstreams posts. In the meantime, let’s all try not to let this Summer fly by too quickly!