Post contributed by Mandy Cooper, Research Services Graduate Intern, and Ph.D. candidate, Duke University Department of History.

When I started as the Research Services intern, I knew that I wanted to do a blogpost for the Rubenstein Test Kitchen. But, where to begin? I spent some time exploring our collections and reading over the previous Test Kitchen blog posts as I thought about what I should make. Finally, I decided that since I’m a nineteenth-century historian, I would make a dish from that era, with a drink to go along with it.

After some initial exploration (relying on Ashley Young’s Guide to Food History at the Rubenstein), I settled on using Lydia Maria Child’s 1836 The American Frugal Housewife. The book was part of a genre of prescriptive literature that gave women advice for fulfilling their domestic duties. Child emphasized how to be a good wife, mother, and hostess while maintaining a frugal lifestyle. Many of the tips and recipes included a reference to it being “good economy” to use specific ingredients over others or to use substitutes for things like coffee. (Though, Child pointed out that in the case of coffee, “the best economy is to go without” which is definitely not an option for this graduate student!)

After looking through the recipes, I decided to make a dessert that I could share with my coworkers at the Rubenstein. I found some mouth-watering options, including an apple pie that sounded delightful. Like most recipes from the nineteenth-century, this one was a bit short on details, both for the filling and the pie crust, but the ingredients were simple.

The Filling

First, I made the filling, which could be easily set aside while I made the pie crust. But, Child didn’t specify how many apples, so I looked at a few other apple pie recipes before deciding to use five apples. I first peeled and sliced all of the apples before putting them all in a pan with about a tablespoon of water. The recipe calls for sugar to taste and says that cloves and cinnamon are good spices for the filling. Since I love cinnamon apples—and already had cinnamon at home—I decided to use cinnamon instead of cloves. I stewed the apples to get them tender, being sure to follow Child’s instructions to stew them “very little indeed,” tasting and adding more sugar and cinnamon as I went to get the flavor right. Child also said “If your apples lack spirit, grate in a whole lemon.” I thought the apples were a bit sweet, so I grated in a bit of lemon zest (thought not a whole lemon!).

The Pie Crust

The recipe for pie crust was also short on specifics, so I looked up other recipes to determine how much flour I should use. I used 2 cups of flour and about 1.5 sticks of butter for the bottom crust and the same for the top. I set aside a half cup of flour and about ¼ stick of butter to use for rolling out the crust like Child instructed. Since I was (attempting) to stay true to the 19th century recipe, I rubbed the rest of the butter into the flour with my hands, until “a handful of it, clasped tight […] remain[ed] in a ball, without any tendency to fall in pieces.” This was harder than I expected and took more time than I had planned. Once the dough stayed clasped in a ball, I wet it with cold water, rolled it out on a floured surface, put small pieces of butter all over it, floured it, rolled it back up, and repeated this process three times. I did the same thing for the top crust, which was a bit easier. After putting the crust in the pie pan, I poured in the apple filling. I then cut strips of the crust to lay over the top of the pie.

I put the pie in the oven for 40 minutes, checked it, and then put it back in for another 10 minutes until the crust turned golden.

Raspberry Shrub

Though according to Child “Beer is a good family drink,” I decided to go with a non-alcoholic drink option and try a raspberry shrub to go with my apple pie.

Child promised that raspberry shrub is “a pure, delicious drink for summer,” and since it looks like summer has officially arrived here in Durham, I thought it would be the perfect addition to my historical recipe experiment.

I used 12 ounces of fresh raspberries and white wine vinegar. After washing the raspberries, I put them in a pot, covered them with vinegar, and brought them to a boil before letting them simmer over medium-high heat until the berries were soft—a bit less than 10 minutes. I then strained the mixture into a glass measuring cup to get out the seeds and pulp of the berries and make measuring easier.

After straining the mixture, I ended up with a little over 1.25 cups of juice, which I poured back into the pot. The recipe called for equal amounts of sugar and juice, so I also added 1.25 cups of sugar. I brought the mixture barely to a boil before taking it off the eye, skimming the foam off the top, and letting it cool. Once it cooled, I poured the juice into a mason jar to store it.

Child said to mix raspberry shrub with water for a “pure, delicious drink,” so I added 4 tablespoons of the juice to a glass of water. Then, since I love mint with raspberry, I added a sprig of fresh mint as a garnish.

The Verdict

The apple pie filling was absolutely delicious. The pie crust, though, didn’t turn out very well, even though it looked beautiful. Despite all of the butter, it was dry and tasted like chalky flour with butter, and it was a bit too thick. I might try an apple pie again, but I would definitely find a different recipe for the crust. (I was nice and didn’t inflict this crust on my co-workers here at the Rubenstein!)

The raspberry shrub was a success! Light, refreshing, and sweet—perfect for summer, just like Child said. I’ll definitely be making it again, though I’ll likely let the juice and sugar mixture simmer for a little longer next time, since there was a very slight taste of vinegar to it still.

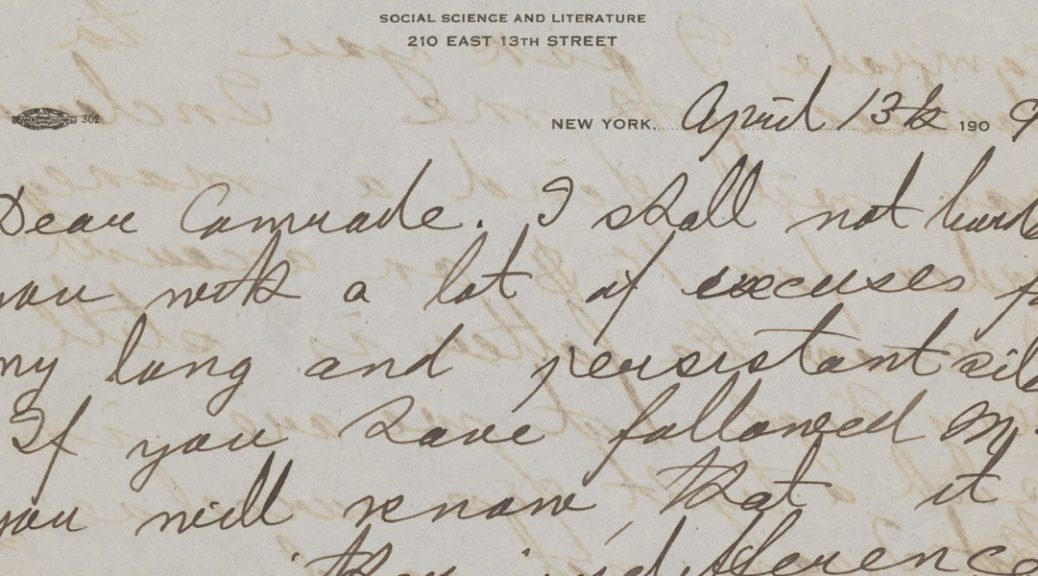

Few anarchists have gained as much mainstream recognition as Emma Goldman, an iconic figure in labor organizing, feminist history, and prison abolition. The

Few anarchists have gained as much mainstream recognition as Emma Goldman, an iconic figure in labor organizing, feminist history, and prison abolition. The

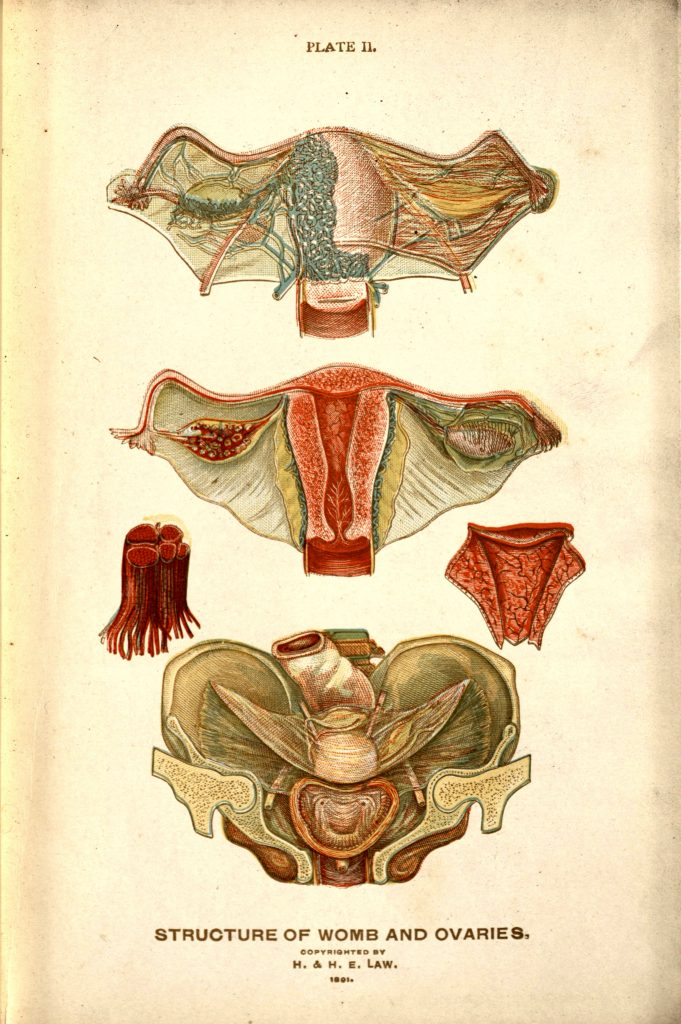

Please join us Monday, April 30th at noon for our next Trent History of Medicine Lecture Series. Raul Necochea, Ph.D., will present Contraception Crossroads: Health Workers Encounter Family Planning in Mid-20th Century Latin America.

Please join us Monday, April 30th at noon for our next Trent History of Medicine Lecture Series. Raul Necochea, Ph.D., will present Contraception Crossroads: Health Workers Encounter Family Planning in Mid-20th Century Latin America.

Date: April 17, 2018

Date: April 17, 2018