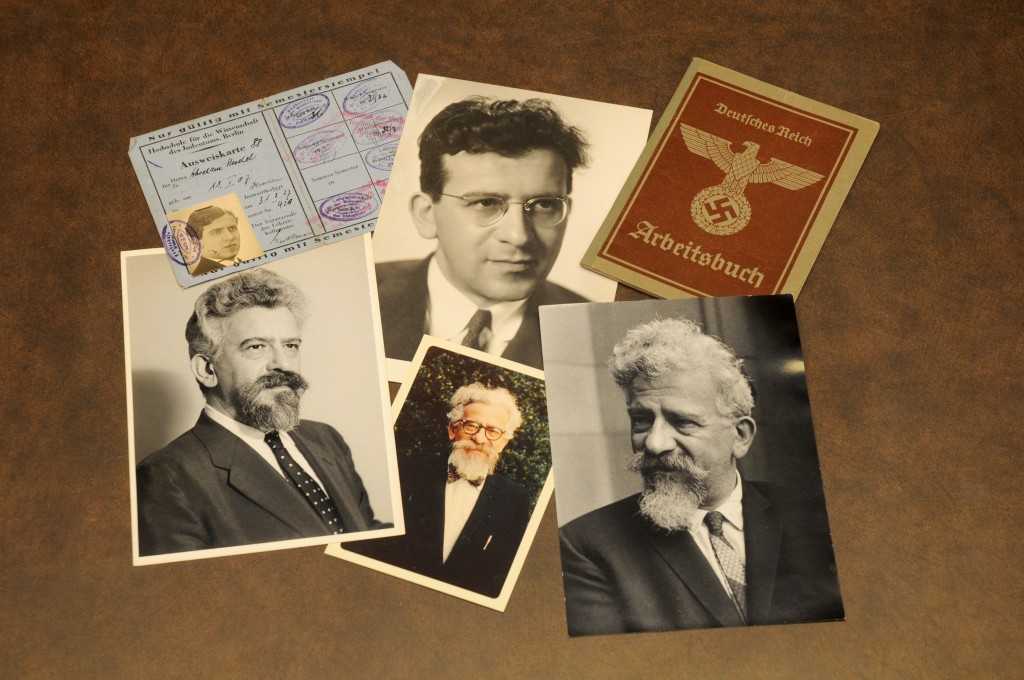

Welcome to the first post in a series documenting the processing of the Abraham Joshua Heschel Papers.

In 1965, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, professor of Jewish Ethics and Mysticism at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, accepted as position as the Harry Emerson Fosdick Visiting Professor at Union Theological Seminary (UTS). Newspapers reported this occasion with headlines that proclaimed “Rabbi to Teach Christians” and “Seminary Gives Post to Heschel.” The prestigious visiting position speaks to Heschel’s influence in Christian-Jewish relations at the time. As we begin processing the Abraham Joshua Heschel Papers, there is evidence that Heschel’s dedication to interfaith work also made him a controversial figure in some Jewish circles. I recently processed a large folder of materials that Heschel collected during his tenure at UTS and discovered that Heschel preserved the views of his dissenters, tucked in alongside his lecture notes and grade records.

In a folder that contains programs from events honoring Heschel at UTS and Eden Theological Seminary and an excerpt from Reinhold Niebuhr’s Pious and Secular America, I found a fascinating newspaper clipping. The article, “Scholar Delimits Interfaith Talks,” discusses another rabbi’s view on interfaith relations. The article explains that Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, professor of Talmud at Yeshiva University, argued that Jews should avoid discussing theological issues in their relations with Christians. This article provides an intriguing counterpoint to the documents promoting Heschel’s theological lectures at Christian Seminaries.

In another folder, which Heschel labeled “Interfaith,” he included an excerpt from a letter written by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson. In the letter, Schneerson writes, “there is no need for us whatever to have any religious dialogues with non-Jews, nor any interfaith activities in the form of religious discussions, interchange of pulpits, and the like” (2). Schneerson concludes, “religious dialogue with non-Jews has no place in Jewish life, least of all here and now” (4). This letter rests alongside an article written by UTS President John C. Bennett and Heschel’s itinerary for the Spring Semester of 1966 which included lectures at the Indiana Pastors’ Conference and eleven different Christian seminaries.

These dissenting opinions preserved by Heschel and included in folders that highlight his interfaith work provide an intriguing glimpse into Heschel’s world. We will leave it up to future researchers to discover the meaning behind Heschel’s inclusion of these opposition opinions in these particular folders!

Post contributed by Adrienne Krone, Heschel Project Assistant in Rubenstein Technical Services.