There’s no denying it: we love the Edwin and Terry Murray Comic Book Collection. The product of 40+ years of collecting by Edwin L. and Terry A. Murray, the Murray Comic Book Collection has far-reaching holdings, from mainstays like DC to smaller publishers like Pacific Comics. It has an enormous volume of materials–almost 290 linear feet, or nearly the height of the Statue of Liberty from the ground to torch (305 feet)![i] And it’s very comprehensive: to quote our finding aid, the Marvel series contains “near-complete runs of Avengers, Captain America, Fantastic Four, Daredevil, Incredible Hulk, Punisher, Spider-Man, Thor, and X-Men.”

The Murray Comic Book Collection has been good to us, providing us with ample opportunities to use its holdings for instruction sessions, reference questions, research, and even blog posts. We want to be good to it, too. With the spirit of the New Year at our backs, we’re embarking on a project to reprocess the titles in the collection as serials. Thus, beginning March 1st, 2016, the Edwin and Terry Murray Comic Book Collection will be closed to researcher use.

You may now be wondering: what’s a serial?

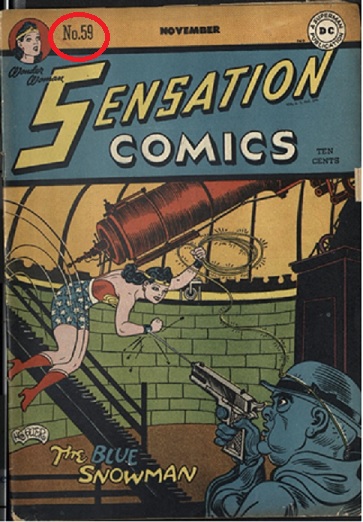

A serial “is a resource issued in successive parts, usually bearing numbering, that has no predetermined conclusion.”[i] When you look at that definition, it’s obvious that many comics are serials. A quick browse of our finding aid shows our comic titles are often issued in successive parts (see the numbering of Sensation Comics below), and there are some that are still going strong after decades of issues. In fact, the Rubenstein has issues of Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories dating from the 1940s!

By thinking of the Murray Comic Book collection as serials rather than as one big collection, we can go over it with a finer toothed comb: we learn even more about what we have, such as when a comic book series spawns a new series, or exactly how many issues we need to make a series complete. With that information, we’re then able to catalog each title individually, creating and/or improving upon records in our library catalog. Once this project is complete, you’ll be able to type in a title—like Action comics—into our search engine, and its very own record will come up. There will be direct access to serial titles, complete with listings of the issues we hold.

As might be expected, this project will take time, which is why we’ve decided to close the collection March 1st. We’ll need to sort those 290 linear feet of comic books, grouping by titles and sleuthing out potential issues. We’ll also look at rehousing the titles in the collection. After that, we’ll catalog them as titles, so that researchers will be able to use their own super powerful research skills to locate our holdings quickly and easily. No lassoing of truth necessary.

Post contributed by Liz Adams, Special Collections Cataloger.

[i]“Statue facts.” The Statue of Liberty Facts. The Statue of Liberty – Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. All Rights Reserved., n.d. Web. 12 Jan. 2016.

http://www.libertyellisfoundation.org/statue-facts

[i]“Serials.” RDA Toolkit. RDA Co-Publishers, n.d. Web. 12 Jan. 2016.

http://access.rdatoolkit.org/

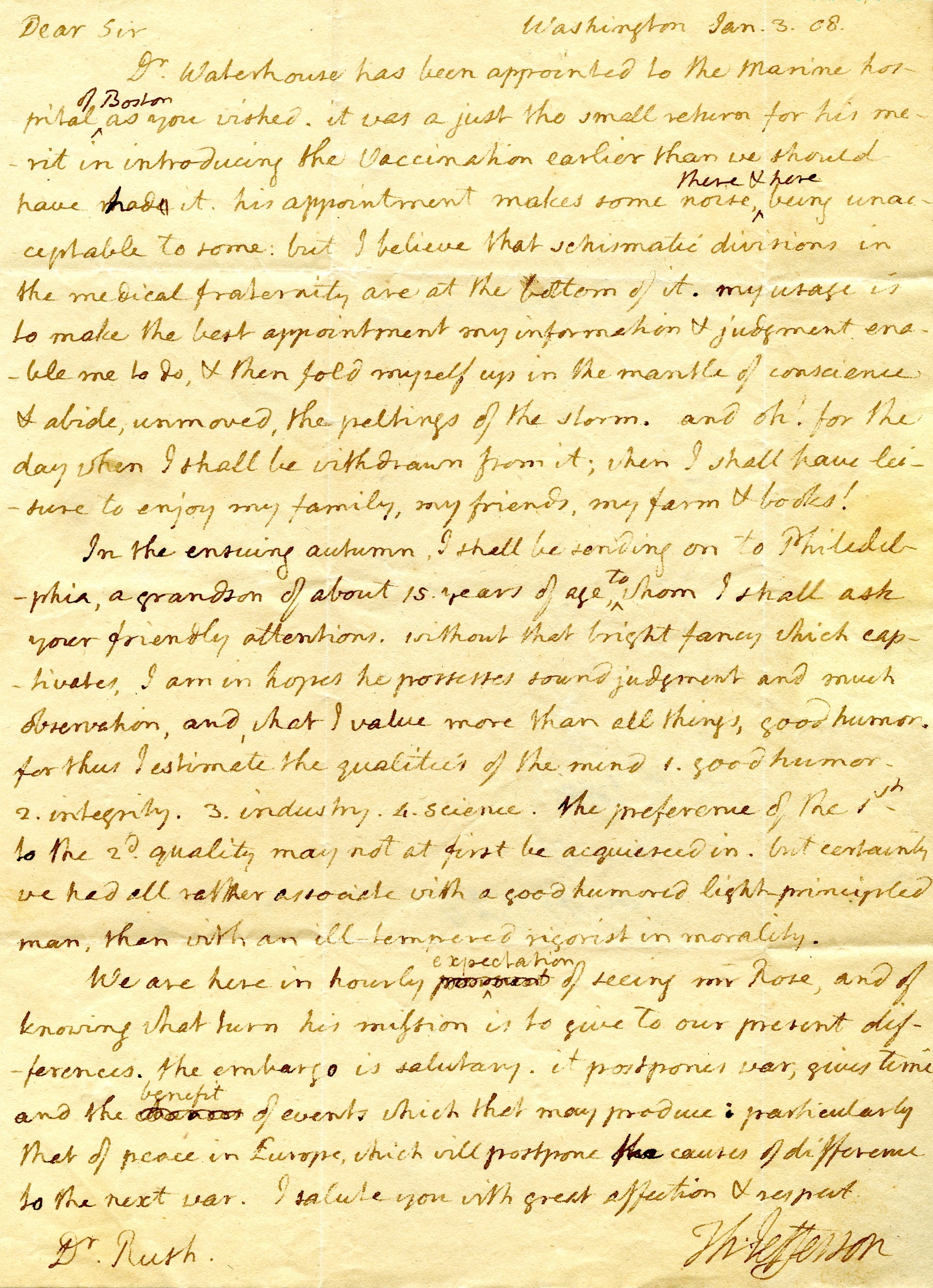

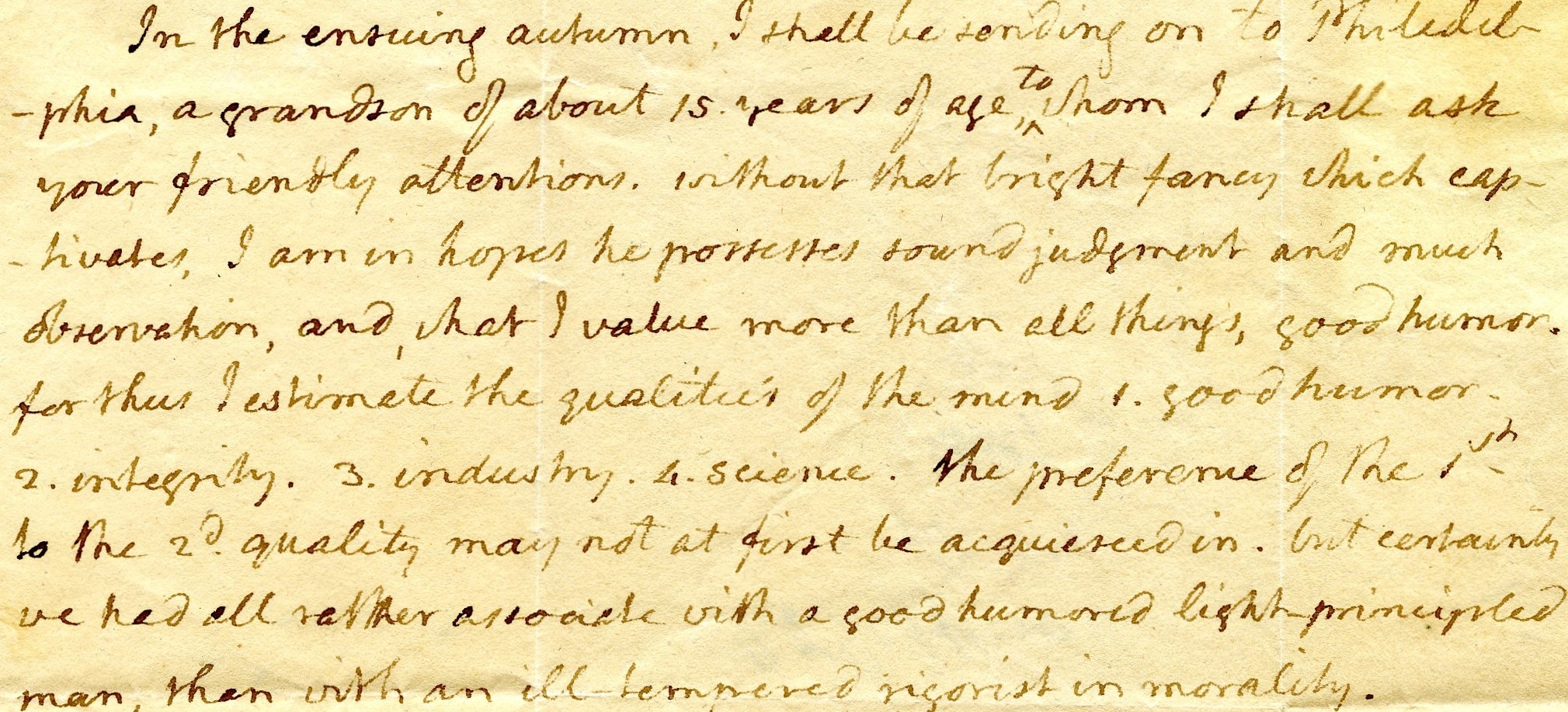

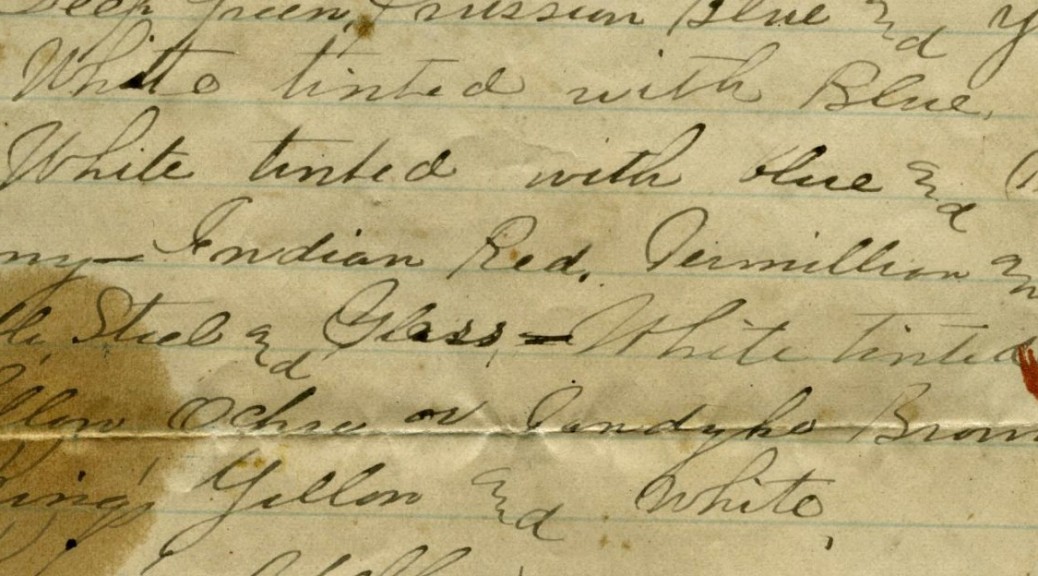

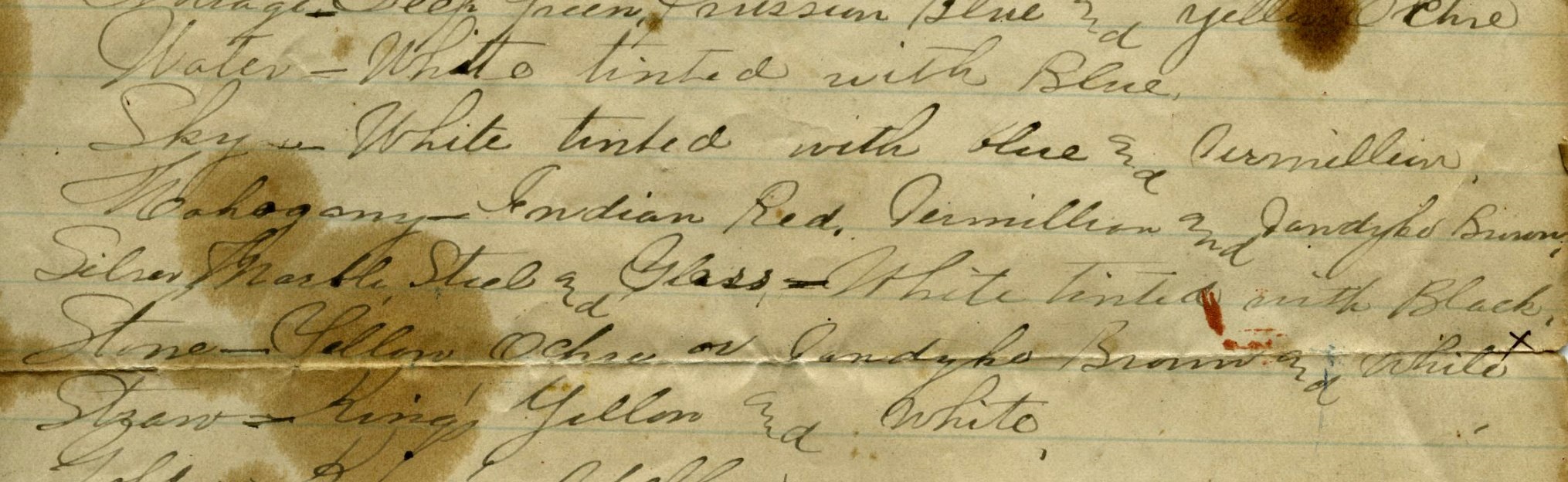

A manuscript (i.e. handwritten) cookbook can tell us a great deal about its creator. What foods were available to her? How would her family have celebrated holidays and birthdays? Was she an elite woman with a cook who could prepare elaborate dishes, or a farm wife who had to prepare simple, hearty fare and preserve her harvest to feed her family? Do the recipes reflect a particular ethnic or religious background or geographical location? As is the case today, routine meals do not require a recipe. It is the special occasion recipes, especially those that require careful measurements to work properly, that are recorded for future reference.

A manuscript (i.e. handwritten) cookbook can tell us a great deal about its creator. What foods were available to her? How would her family have celebrated holidays and birthdays? Was she an elite woman with a cook who could prepare elaborate dishes, or a farm wife who had to prepare simple, hearty fare and preserve her harvest to feed her family? Do the recipes reflect a particular ethnic or religious background or geographical location? As is the case today, routine meals do not require a recipe. It is the special occasion recipes, especially those that require careful measurements to work properly, that are recorded for future reference.