I was awarded a Mary Lily Research Grant in 2014 to travel to the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture to consult The Kathy Acker Papers. In April 2014 I carried out research in the archive for my book manuscript, Kathy Acker: Writing the Impossible, which is under contract with Edinburgh University Press.

Critics and scholars in the field of contemporary literature have largely understood Kathy Acker as a postmodern writer. My monograph challenges such readings of the writer and her works, paying close attention to the form of Acker’s experimental writings, as a means to position Acker and her work within a lineage of radical modernisms.

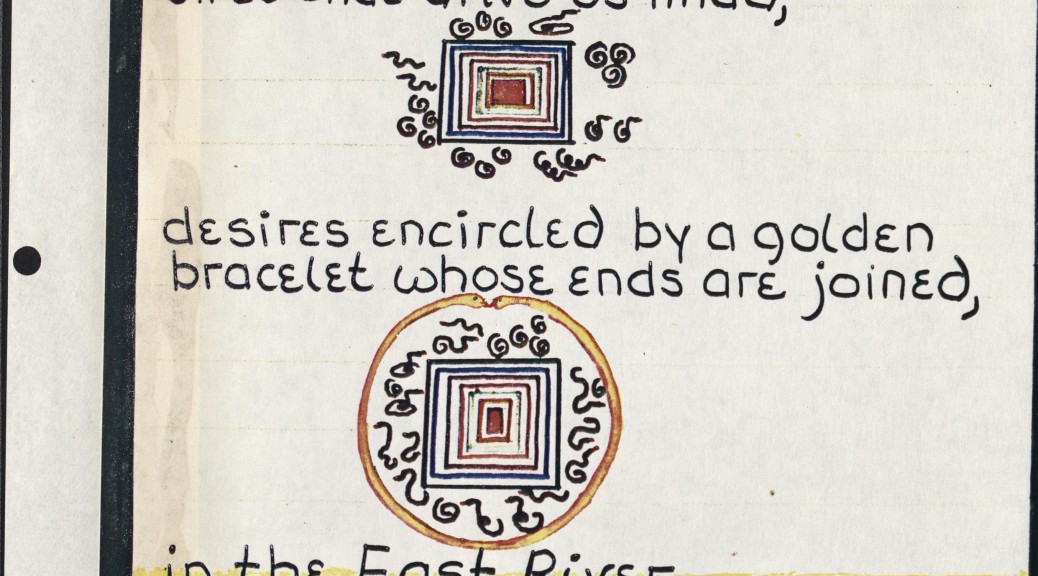

Consulting The Kathy Acker Papers, the extensive archive of Acker’s works housed at the Sallie Bingham Center, shaped my research in a number of ways. Most striking, and perhaps the aspect of the archive that has been most formative to my work, is what the archive revealed in terms of the materiality of Acker’s various manuscripts. The original manuscript of Acker’s early and most renowned work, Blood and Guts in High School (1978), is a lined notepad with text and image pasted onto the pages. It is a collage, an art object. The dream maps, which punctuate Blood and Guts in High School, are archived as separate framed objects. Dream Map Two is an artwork measuring 56 inches by 22 inches. Such archival discoveries enabled the development of my book. The monograph takes a specific work of Acker’s for each chapter as a means to explore six key experimental strategies in Acker’s oeuvre. A substantial knowledge of Acker’s avant-garde practices would not have been possible without the research carried out in the archive.

The Kathy Acker Papers also illuminated a related line of enquiry taken in my monograph: the importance of Acker’s early poetic practices to an understanding of her later prose experiments, which often dislimn the distinction between poetry and prose. The repository of unpublished poetic works provided rich material for the first chapter of my book, which explores Acker’s engagement with the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets in the 1970s. Acker’s unpublished poetry can be understood as both a significant autonomous body of work, and as juvenilia that was a catalyst for her later writing experiments. The box that houses these early works also contains typed conversations between Acker and her early mentor, the poet David Antin. Written under Acker’s early pseudonym, The Black Tarantula, these conversations point to the discourses that emerged between Acker and various writers and poets concerning the uses of language. In this 1974 text, ‘Interview With David Antin’, which reads in part, and perhaps intentionally, like a Socratic dialogue, Acker and Antin interrogate issues of language and certainty. Acker and Antin draw on their writing experiments, alongside a discussion of Wittgenstein’s On Certainty, as means to interrogate language and perception. Such materials are rich when read in conjunction with Acker’s poetry.

Reading the materials in the archive, letters, early drafts of published works, speeches, Acker’s teaching notes and notebooks on philosophy, as well as Acker’s handwritten annotations on various texts, and her invaluable collection of small press pamphlets, was illuminating. Numerous texts disclosed the self-conscious nature of Acker’s experiments. A number of early poetic experiments are entitled ‘Writing Asymmetrically’, and several notebooks gesture specifically to the influence of William Burroughs and Acker’s experiments with the cut-up technique. Other notebooks are streams of consciousness, and are evidently comprised of material that Acker then cut up for use in her experimental works. Most of Acker’s novels originated this way, as a set of handwritten notebooks.

Archival research at the Sallie Bingham Center cultivated a rich understanding of the diversity of Acker’s experimental work and the writer’s remarkable lifetime achievements, many of which remain unpublished. The extent of the material and its uniqueness brought home the importance and centrality of the archive in the formation of knowledge regarding an experimental writer’s oeuvre. In the context of the female avant-garde writer, Acker stated that Gertrude Stein, as the progenitor of experimental women’s writing, is ‘the mother of us all.’ The remarkable experimentalism and the linguistic innovation of a great number of the texts that comprise The Kathy Acker Papers reveal Acker to succeed Stein as one of the most important experimental writers of the twentieth century.

Post contributed by Georgina Colby, Lecturer in Contemporary Literature, University of Westminster, UK.