Post contributed by Ashley Rose Young, a Ph.D. candidate in History at Duke University and the Business History Graduate Intern at the Hartman Center.

One of the Duke Libraries’ most popular blog series is the Rubenstein Test Kitchen. For this series, we invite library staff and affiliated scholars to recreate historic recipes, some of which delight and some of which cause fright (wiggly meat jell-o, believe it or not, isn’t as appealing as it once was to the American consumer). Our contributors exercise a fair amount of creativity and patience as they replicate decades- or even centuries-old recipes. Their trials and tribulations at the stovetop are indicative of the culinary skills and know-how that can be lost in translation. For example, many historic gumbo recipes begin with the phrase, “First you make a roux,” but do not provide instructions for how to actually make the roux. The creators of those recipes assumed that readers would have mastered the challenging technique of slowly toasting flour in fat, which, in the 1800s was common knowledge. Many Americans today, however, would not know how to start a roux or even know that it is a traditional base for sauces and soups. Recipe writing and replication are no easy tasks.

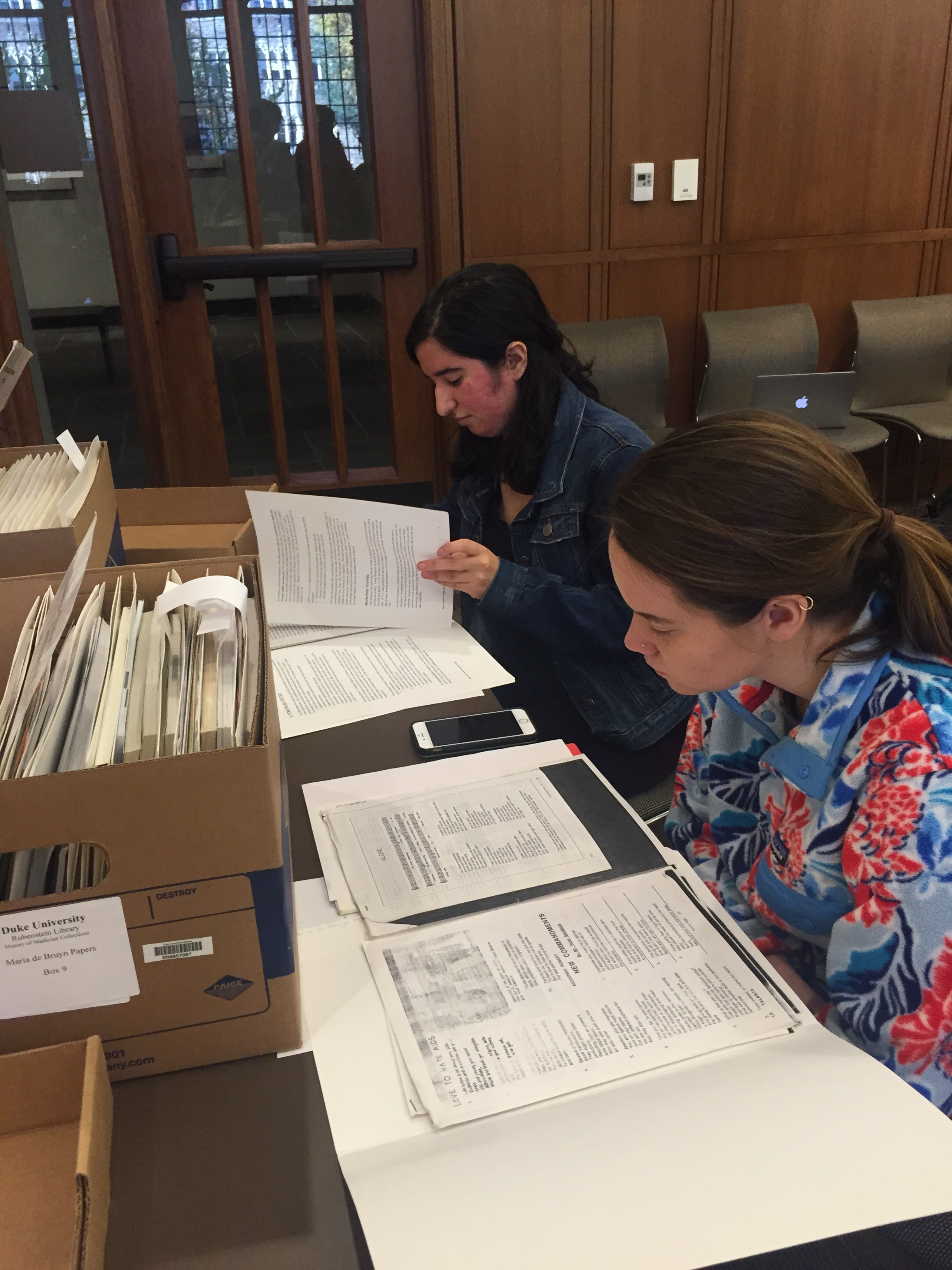

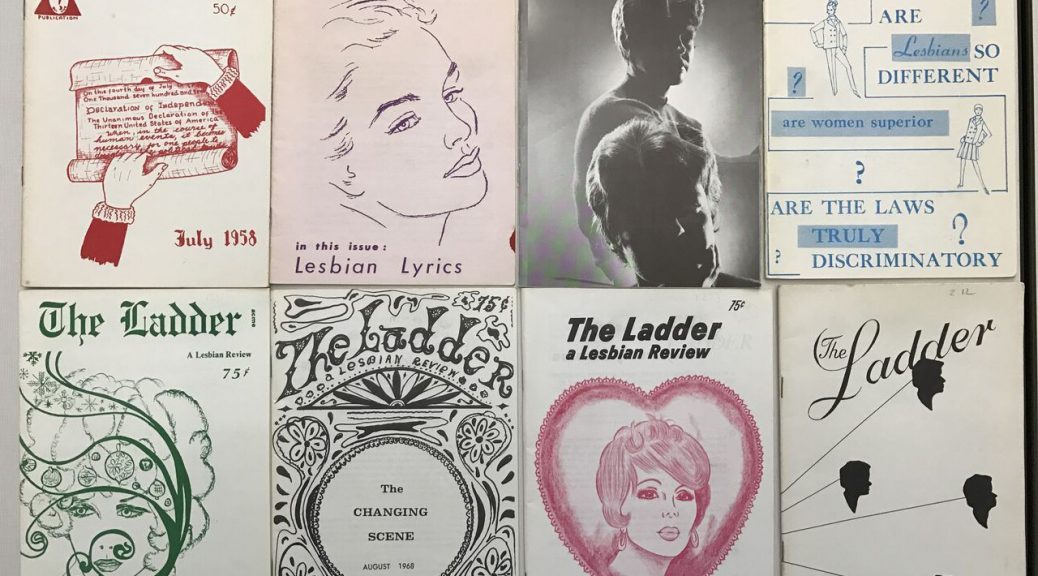

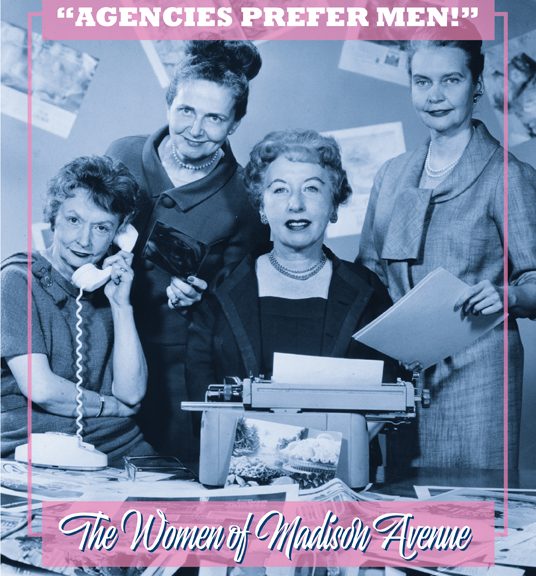

Reflecting on our popular posts, a question came to mind: where did test kitchens originate? After co-curating our most recent exhibit, “Agencies Prefer Men!” The Women of Madison Avenue, I learned that the early history of test kitchens is actually tied to advertising agencies.

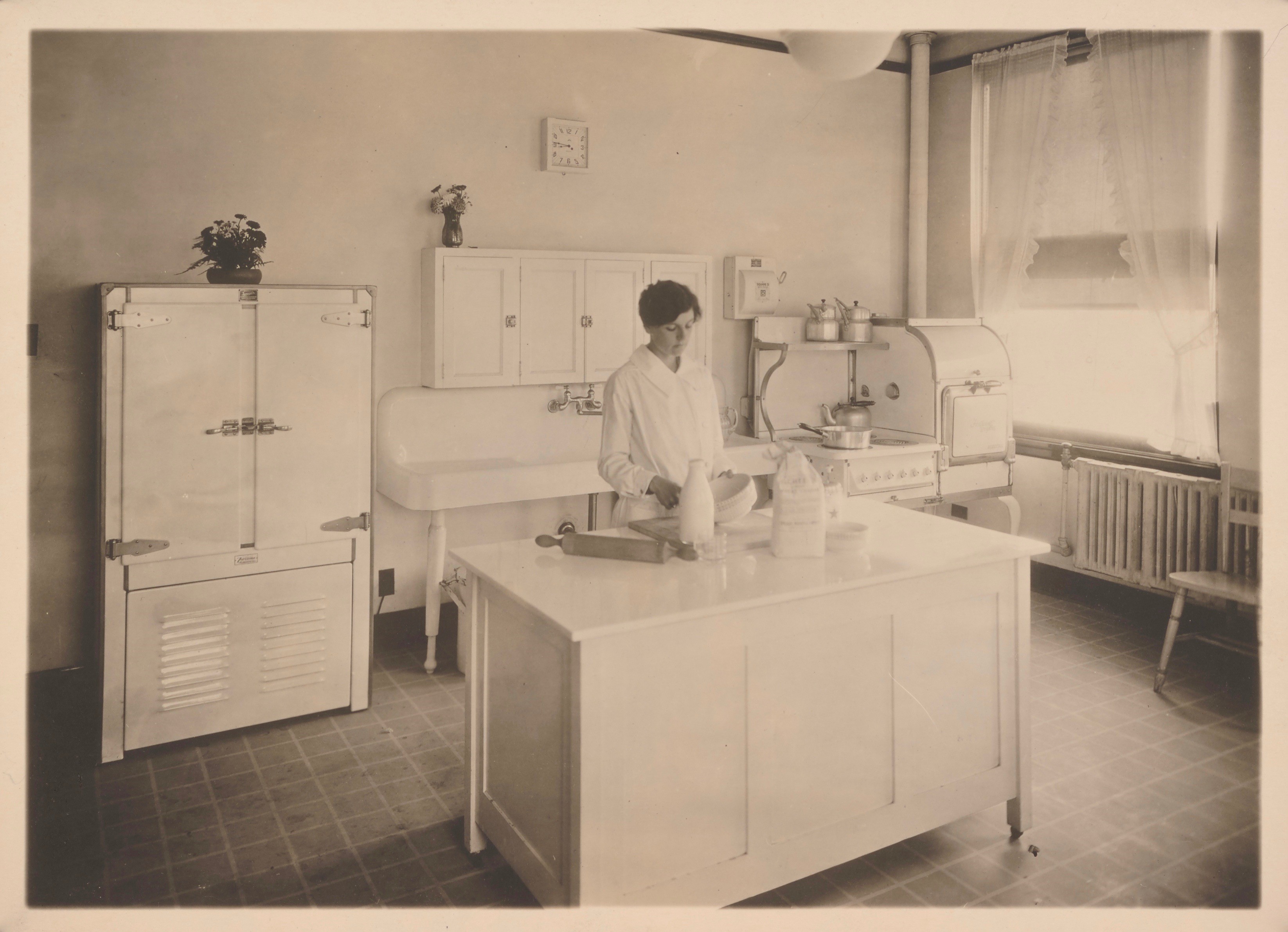

In 1919, the J. Walter Thompson Company (JWT) was the first advertising agency to invest in an on-site home economics service and test kitchen. The initial purpose of the kitchen, according to the JWT News Bulletin, was simple: “to invent and test recipes” in order to instruct women “how to get the best results with the greatest economy.” The kitchen was located in the Chicago office, which catered to important clients in the food industry, including Libby, Kraft, and Quaker.

As the test kitchen matured, its goals diversified to fit the demands of JWT clients. Researchers in the test kitchen, for example, worked to discover new uses for client products so as to increase sales opportunities in new fields. The test kitchen also had an important relationship with the art department at JWT. Researchers prepared dishes and brought them to the art team to be photographed for print advertisements. Those early experiments regularly failed because the food quickly lost its luster and thus looked unappetizing in photos. After an hour or so, for example, flaky biscuits and airy souffle no longer looked fresh. In order to remedy this issue, JWT employed home economics experts and renovated the test kitchen space, turning it into an “art gallery” for prepared foods. JWT understood the importance of the adage, “we eat with our eyes first.” The efforts of JWT paid off. As recounted in the News Bulletin, “The piping hot biscuits of the copy were made ten times as attractive by the delicate flakiness of the samples in the illustration.”

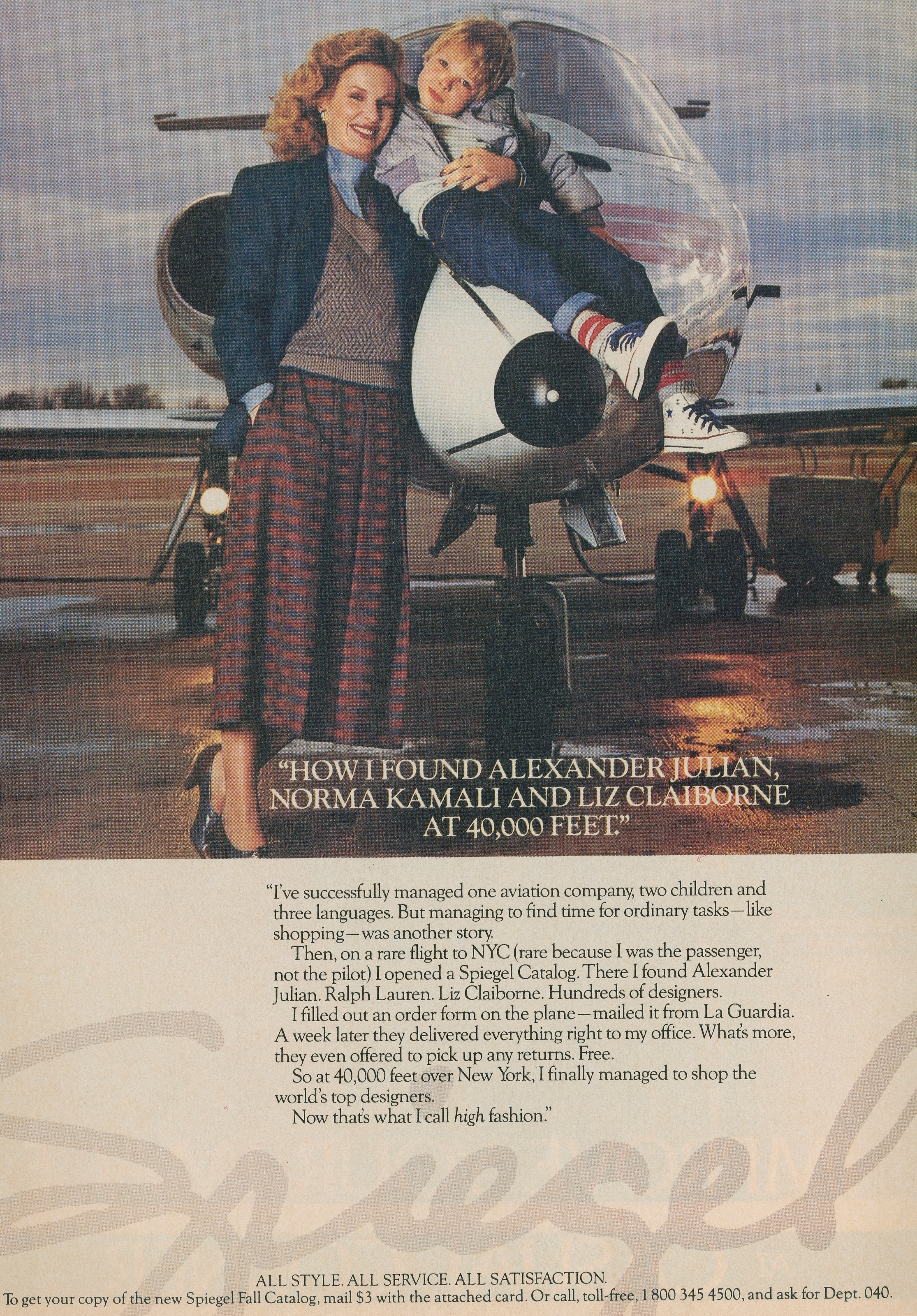

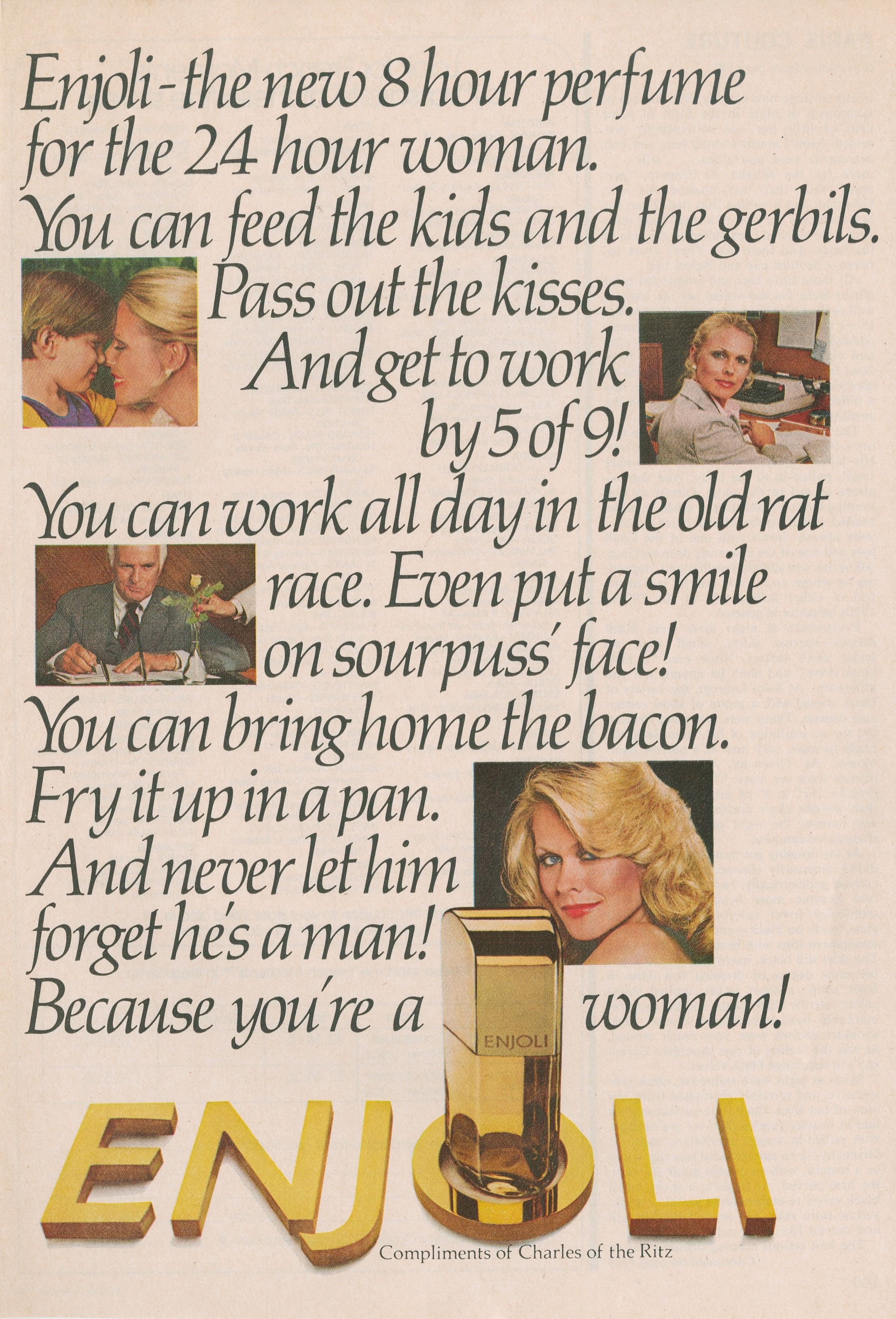

In this laboratory, test kitchen staff also created recipes to include in print advertisements. For example, they would have tested Libby’s products like Hawaiian Sliced Pineapple and Pineapple Juice before the agency designed advertisements for publication in magazines like The Ladies’ Home Journal.

In time, the test kitchens of JWT not only functioned as places to present foods more effectively in advertising, but also as places that defined the trajectory of American cooking. As reported in the September 1958 JWT newsletter, the Home Economics Center was “an endless source of food ideas of all kinds.” As a promotion for their client, French’s mustard, JWT created a new recipe for meatloaf that featured a tangy mustard meringue on top of a mustard-laced loaf. The researchers also created a recipe for a heartier pizza crust made with French’s mustard. These innovative uses for ordinary products helped boost sales for many of JWT’s clients, bolstering the company’s reputation as one of the most dynamic and influential advertising agencies in the world.

As we ready ourselves for the next round of Rubenstein Test Kitchen posts, I hope that our contributors think back on the paramount role that test kitchen researchers played in the making of the modern American palate, including the fascinating recipes preserved in our archives.

You can learn more about the JWT test kitchen researchers and their contemporaries in advertising via the “Agencies Prefer Men!” The Women of Madison Avenue exhibit, open through March 17, 2017 in the Mary Duke Biddle Room at the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Join the Hartman Center in celebrating its 25th Anniversary with its second event in the anniversary lecture series focusing on Women in Advertising. Helayne Spivak, Director of the Brandcenter at Virginia Commonwealth University, will speak about the status, achievements, and challenges women face in the advertising industry today as well as reflect on her own career and women mentors she has had.

Join the Hartman Center in celebrating its 25th Anniversary with its second event in the anniversary lecture series focusing on Women in Advertising. Helayne Spivak, Director of the Brandcenter at Virginia Commonwealth University, will speak about the status, achievements, and challenges women face in the advertising industry today as well as reflect on her own career and women mentors she has had.