Jennifer Blomberg, senior conservation technician, is leaving Duke today to become the Head of the Collections Management Branch in the Division of Archives and Records in the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources.

Jennifer Blomberg, senior conservation technician, is leaving Duke today to become the Head of the Collections Management Branch in the Division of Archives and Records in the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources.

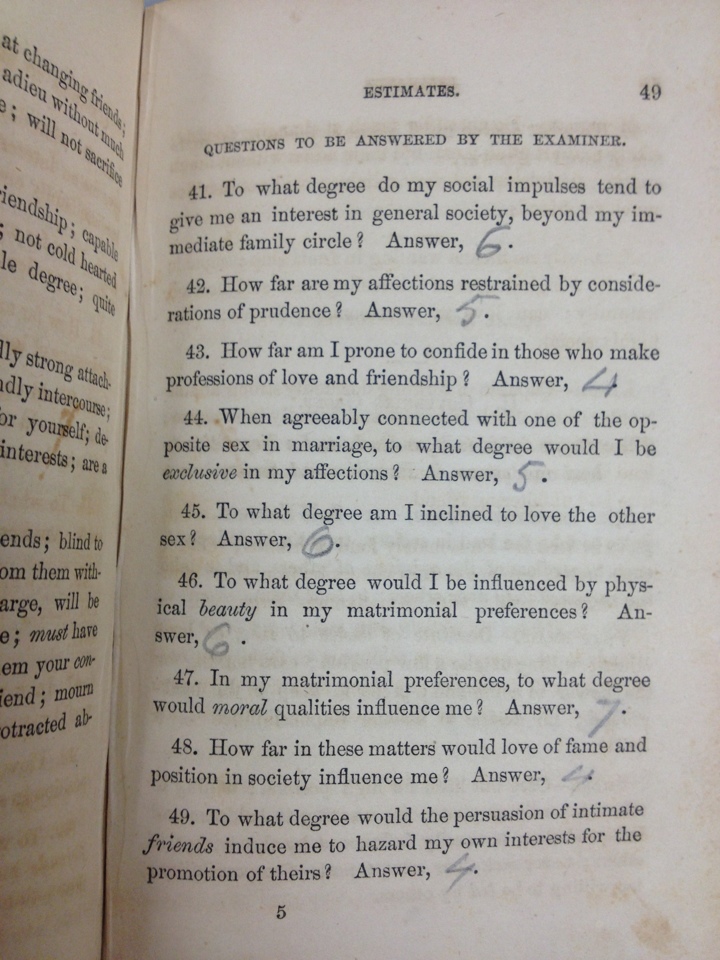

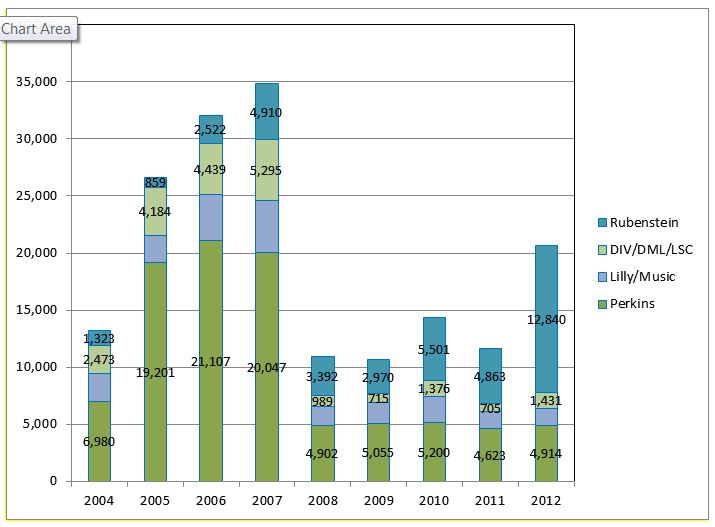

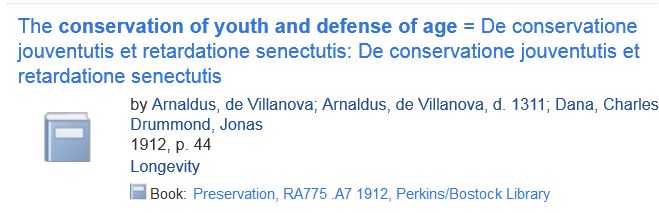

Jennifer started in conservation in February 2011. While working at Duke she completed her Masters of Library and Information Science with a specialization in Archives, Preservation and Records Management from the University of Pittsburgh School of Information Sciences.

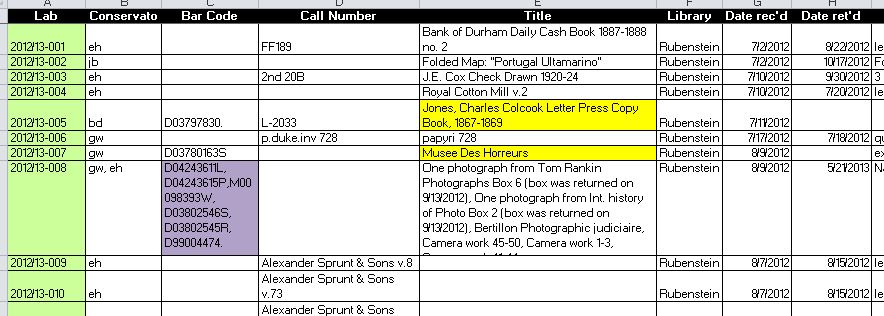

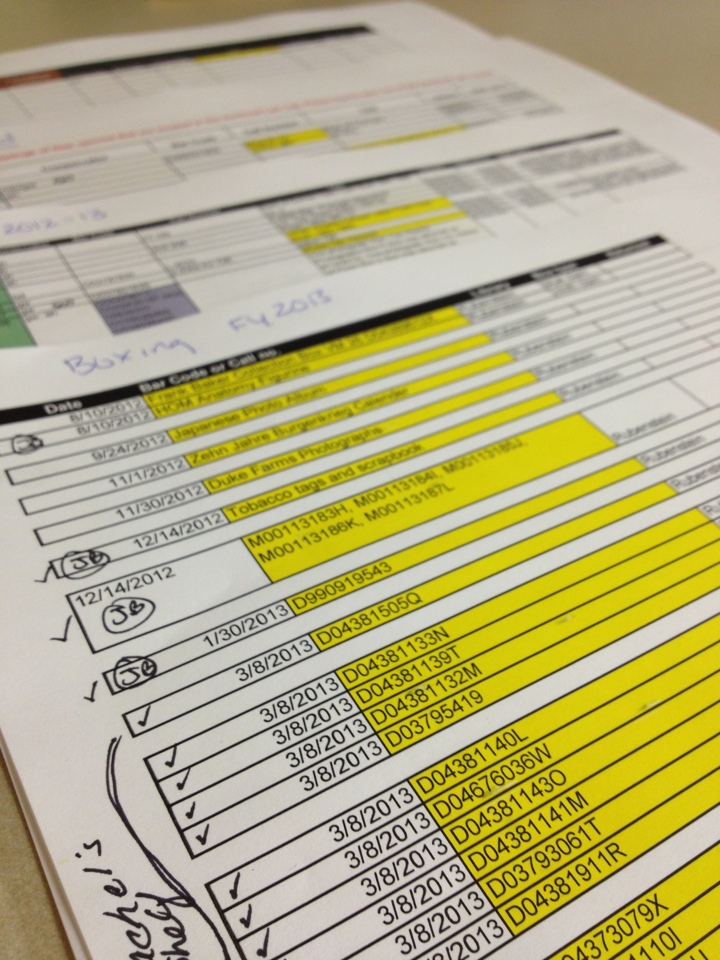

Her many accomplishments include organizing and streamlining our supply inventories and ordering processes, serving as our registrar for special collections materials coming to and leaving the lab (no small feat!), and most recently helping update the library’s disaster plan.

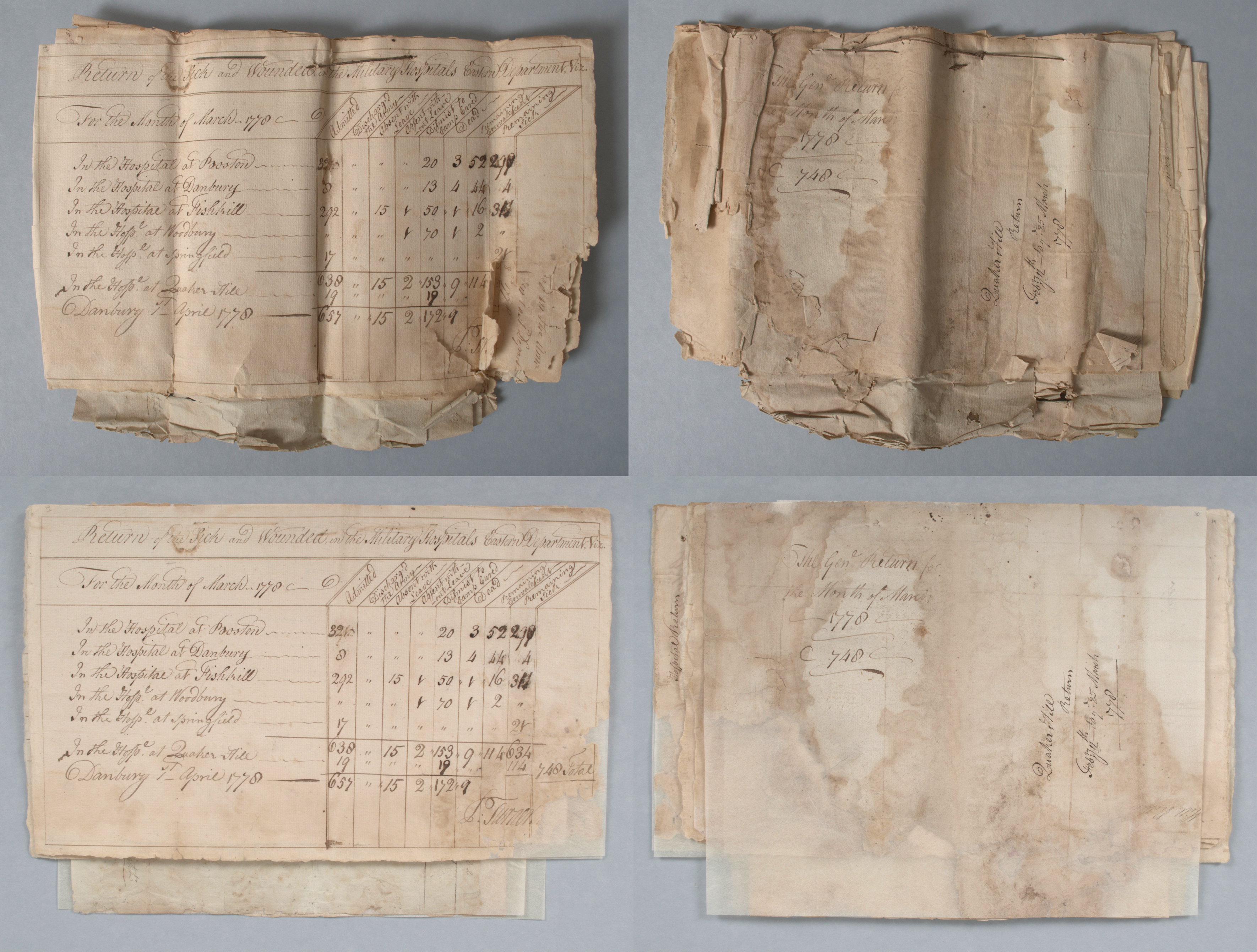

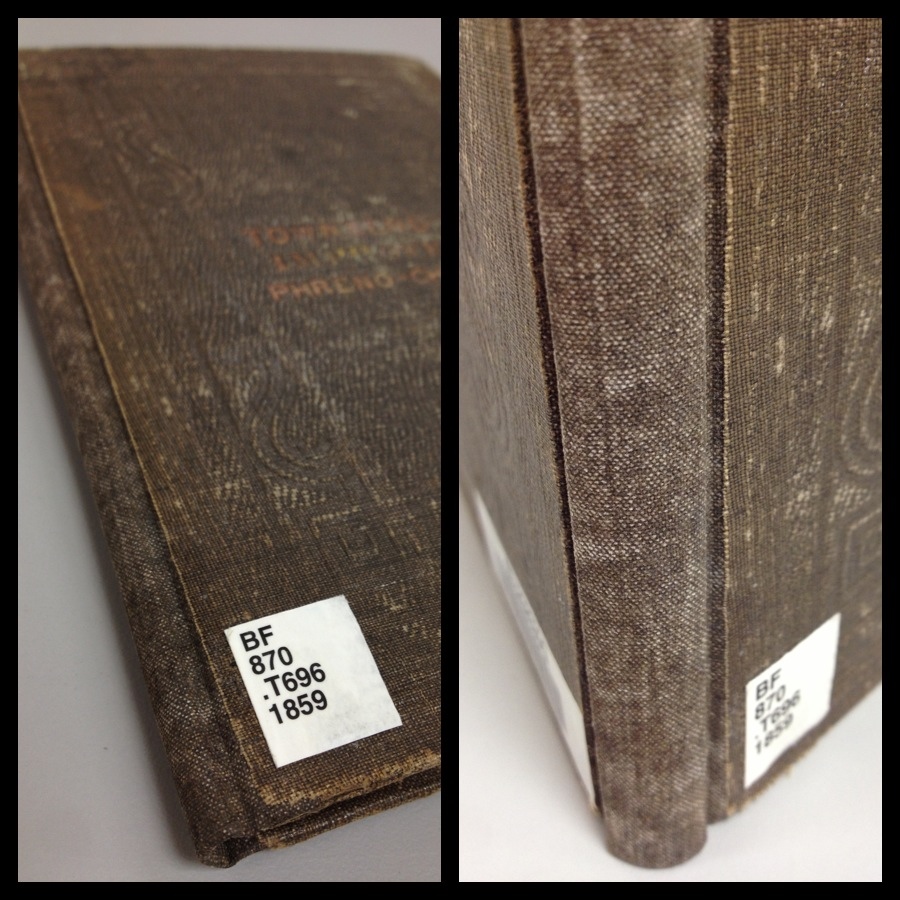

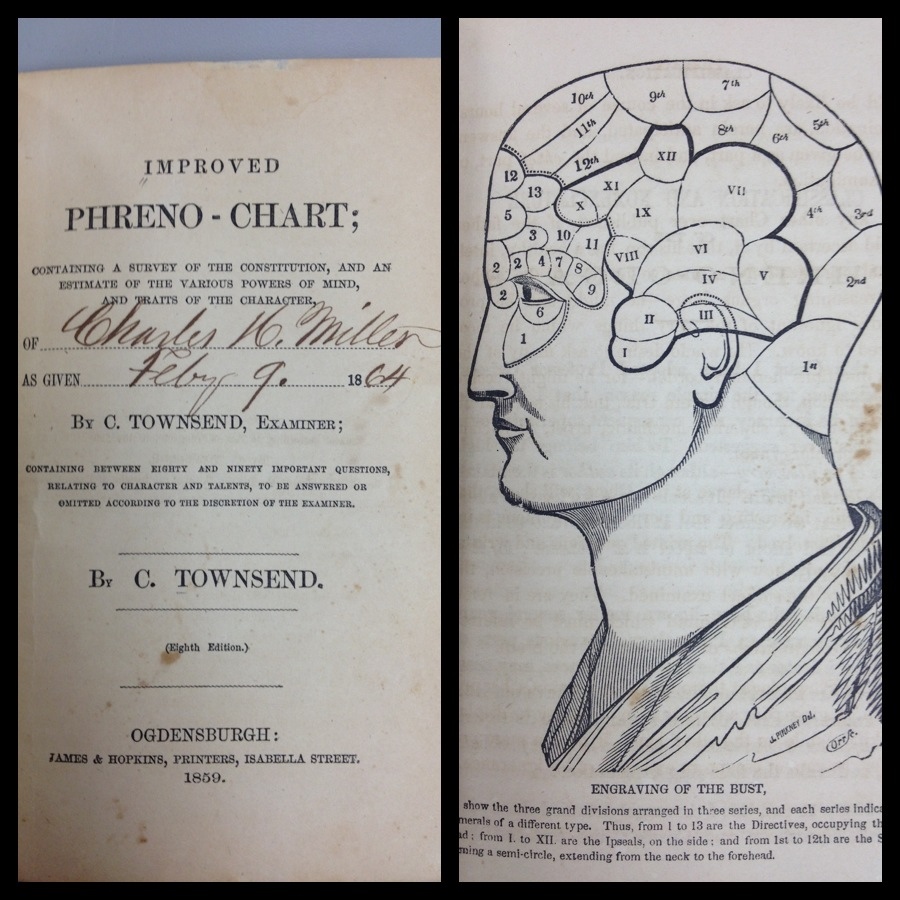

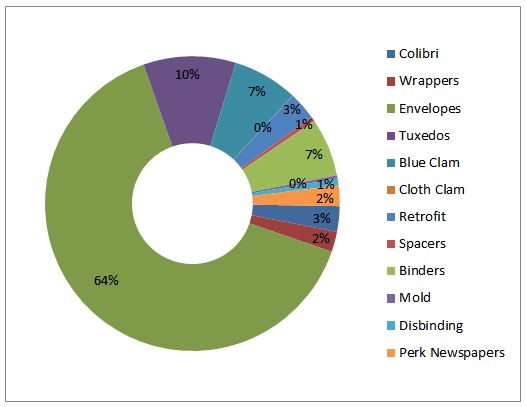

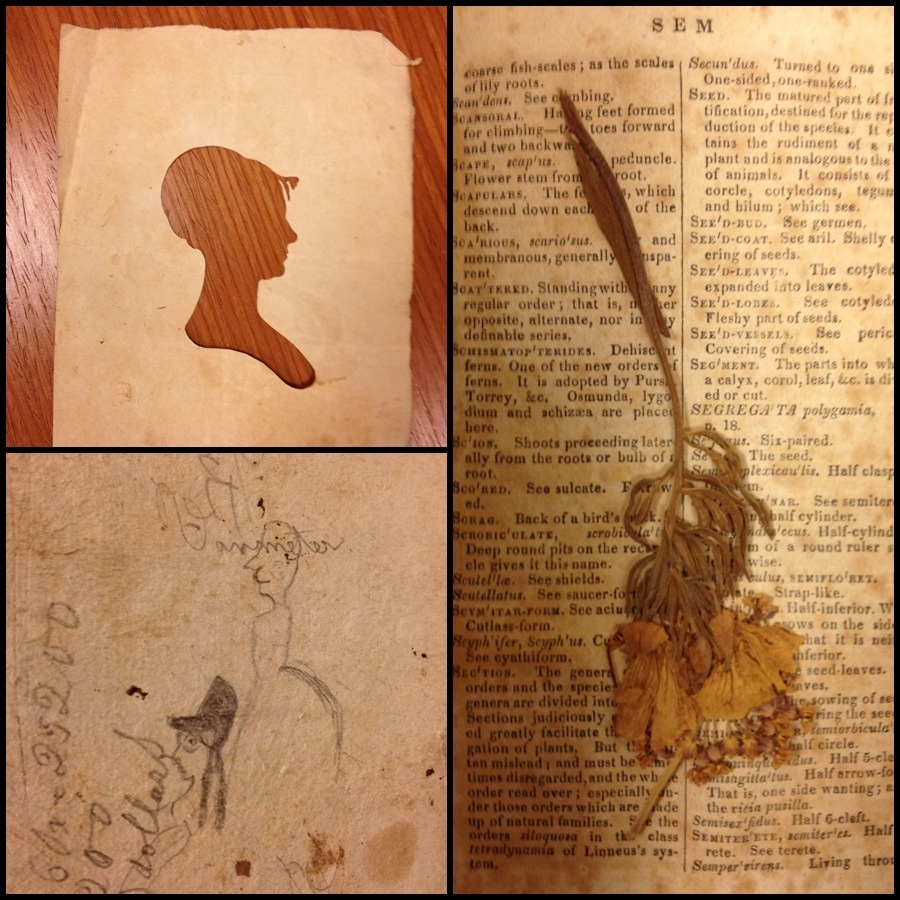

She has cleaned 1,622 items of mold, spent 260 hours installing exhibits, made 149 exhibit cradles for weird things like crocodile skulls and herbarium specimens, and repaired or made enclosures for over 9,000 items from special collections.

Jennifer is our resident specialist in making enclosures for NBO’s, non-booklike objects from the collections. Some of the items she has boxed include a gravestone, death mask, giant papier-mâché puppet, weathervane and World War II Japanese ceremonial swords.

We are sad to see her go, yet excited to see Jennifer start her professional career as a preservation librarian. Congratulations Jennifer, we will miss you and wish you all the best in your new job.