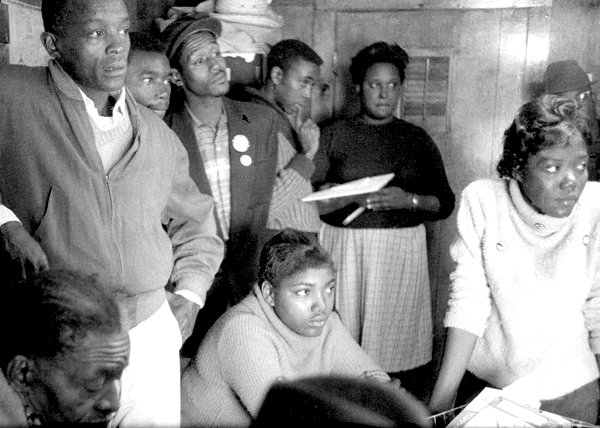

On the surface, writing a 500-word profile about a SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) field secretary or a Mississippi-beautician-turned-grassroots-organizer doesn’t seem like a formidable task. Five hundred words hardly takes ten minutes to type. But the One Person, One Vote project is aiming for more than short biographies; it’s trying to capture why each individual was important to the movement and show that using stories. So this is how we craft a profile in 7 steps:

Step 1: Choose a person

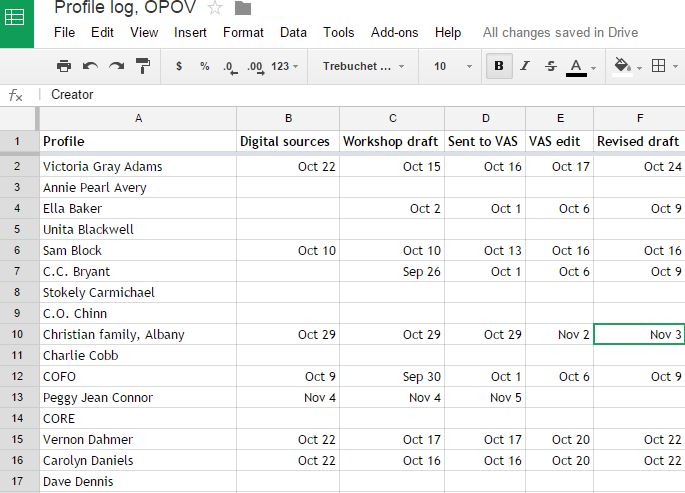

Back in June, the Editorial Board generated a list of people that the One Person, One Vote site needed to profile in order to understand SNCC’s voting rights activism. In less than an hour, we had a list of over a hundred names that included SNCC field secretaries, local people, movement elders, and everyone in between. And those were only the first names that came to mind! We narrowed that list down to 65 people, and that’s what the project team has been working from.

Step 2: Find out everything you can about the person

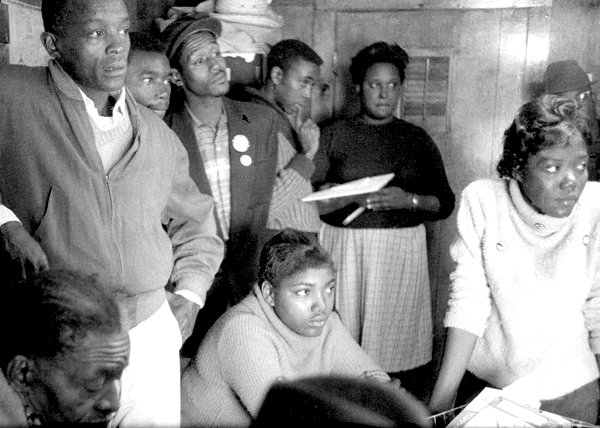

The first step in profile writing is research. We have a library of twenty books for instant referencing of secondary sources. Next comes surveying available primary sources. Our profiles include documents, photographs, audio clips, news stories, and other items created during the movement to make historical actors come to life. Some of our go-to places to find these sources include: Wisconsin Historical Society’s Freedom Summer Digital Collection, the Civil Rights History Project at the Library of Congress, the Joseph Sinsheimer interviews and SNCC 40th Anniversary Conference tapes at Duke University, the Civil Rights in Mississippi Digital Archive at the University of Southern Mississippi, the University of Georgia’s Civil Rights Digital Library. There are more, of course, but that’s the start.

Step 3: Figure out why the person you’re profiling was important to the movement

The central question behind every profile the project team writes is: who was _______ to the movement? Once you start filling in the blank, the answers vary to an incredible degree. Movement elders like Ella Baker and Myles Horton contributed to the movement in different, yet equally important ways as Mississippi-born field secretaries like Charles McLaurin, Sam Block, and Willie Peacock. Trying to figure out how and why is no small undertaking. This is where the guidance of our Visiting Activist Scholar helps focus the One Person, One Vote site on the themes that were at the heart of the movement: grassroots activism, community organizing, and individual empowerment.

Step 4: Use stories to express that in 500 words

Next, spend hours trying to express who the person you’re profiling was to the movement in only five hundred words. The profiles on the One Person, One Vote site aren’t mini academic biographies. Instead, we try to tell stories that illustrate who the people were and how their lives and work influenced SNCC’s voting rights activism in the 1960s. Finding the right story to highlight these central themes is key, and telling it well takes time and (lots of) revision.

Step 5: Workshop profile draft with project team

The first draft of every profile is workshopped with the One Person, One Vote project team (made up of 4 undergrads, 2 graduate students, and the project manager). As a group, we suggest how profiles can better convey their central theme, make sure that the person’s story is readable and compelling, line edit for clunky writing, and go through the primary sources.

Step 6: Send to Visiting Activist Scholar for editing

All of the revised profile drafts go the Visiting Activist Scholar for a final round of editing. Charlie Cobb, a journalist and former SNCC field secretary, is our first Visiting Activist Scholar. He helps bring the profiles to life in ways that only someone who was a part of the movement can. Charlie adds details about events, mannerisms of people, and behind-the-scene stories that never made it into history books. While the project team relies on available primary and secondary sources, the Visiting Activist Scholars adds something extra to the profiles on the One Person, One Vote site.

Step 7: Voila!

Profiles goes through one last proofreading and polishing. Then come 2015, the will be posted on the One Person, One Vote site and the primary sources will be embedded and linked to from the Resources section of the profile pages. Voila!