Digital projects at Duke University Libraries are created and maintained by staff from throughout the Libraries. One of the many departments supporting this work is Assessment and User Experience (AUX). We currently have a staff of five.

Emily Daly

Position: Head of Assessment & User Experience; Librarian for Education

Length of time at Duke: 8 years

What I do at the Library: As Librarian for Education, I help staff the Perkins Help Desk, lead library instruction sessions, teach a half-credit course for the Program in Education, and provide support for students and faculty across the university who are engaging in education-related research. As Head of AUX, I help lead and coordinate DUL staff members’ efforts to assess the effectiveness of our library collections, services and our physical and virtual spaces, and then attempt to improve our services and resources based on our researchers’ feedback. I do this in close collaboration with my talented colleagues Tom, Joyce, Ian and Jeremy. I also serve as a pre-major advisor for 6 first-year students or sophomores.

I think Assessment and User Experience matters in the life of the Duke community because DUL staff provide a range of services and resources to a large group of researchers whose needs are varied and continuously evolving. We work to understand what our users need to conduct their research as effectively and, in many cases, as efficiently as possible. We evolve our services, spaces and resources to meet their changing needs. That, and on a selfish note, it’s really fun and engaging to talk with students and faculty who care deeply about their research.

On the most unexpected trip I ever took I handed in my resume at the public library in Casper, Wyoming. Three weeks later and with virtually no work experience in libraries, I started as Natrona County Public Library’s first full-time Teen Services Librarian (or “Specialist,” since I didn’t yet have an MSLS). I thought I’d be at the library for a year and then return to teaching high school English — I was just waiting for a position to become available. It’s been 11 years since I submitted that resume, and in that time, I’ve worked as a public librarian, school librarian and academic librarian.

If I could take a month to intensively learn one new thing it would be human development with an emphasis on early childhood development, education policy, or web design/development — it’s too hard to pick just one thing to study, which is one reason I became a librarian.

Something memorable that I never expected to see at Duke was college seniors in black graduation gowns walking the quad and stopping periodically to put their hands over the heads and chant. I know now it’s linked to a secret society of some sort, but that’s the extent of my knowledge, and I’m okay with leaving it that way.

What I am currently reading for pleasure: Americanah, by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

Another tidbit about me (related to the pic) is that one of my guilty pleasures is ice cream, and I’m proud to say I’ve passed on my weakness for it to my sons, 5 ½ year-old Philip and 2-year-old Patrick.

Ian Sloat

Position: AUX Student Assistant

What I do at Duke and at the Library: I am a graduate student in the MALS program and at the library I have mostly been working on updating signage and usability studies.

How long have you been at Duke? Just over one year as a student and 5 months at Perkins.

I think Assessment and User Experience matters in the life of the Duke community because it provides us with evidence that we can use to better improve the library for all of the members of the Duke community.

On the most unexpected trip I ever took, I was living in Scotland as an exchange student and I decided to take a trip to the highlands. I got off the bus in Loch Ness to go to the hostel I booked before I left. I walked up to the hostel as the bus was pulling away and when I got to the door, they had a sign up saying they were closed for the season. I stood outside (in the rain of course) for 3 hours until I hitched my way 20 miles north to Inverness and found a cheap hotel for the night.

If I could take a month to intensively learn one new thing it would be a second language, I took French for 9 years growing up in Canada, but I can’t speak a lick of it, so maybe something else.

Jeremy Zhang

Position: Undergraduate Assessment and User Experience Assistant

What I do at Duke and at the Library: I am currently an undergraduate student studying Electrical and Computer Engineering and Economics. In the library I help conduct research and produce both qualitative and quantitative data on many facets of the library. I also help develop and edit the main library website.

I think Assessment and User Experience matters in the life of the Duke community because it is important to streamline processes for students and researchers conducting research or working on their daily homework.

If I could take a month to intensively learn one new thing it would be how to produce electronic music.

What I am currently reading for pleasure: Understanding Wall Street, by Jeffrey Little.

Joyce Chapman

Position: Assessment Coordinator

Length of time at Duke: 3 ½ weeks

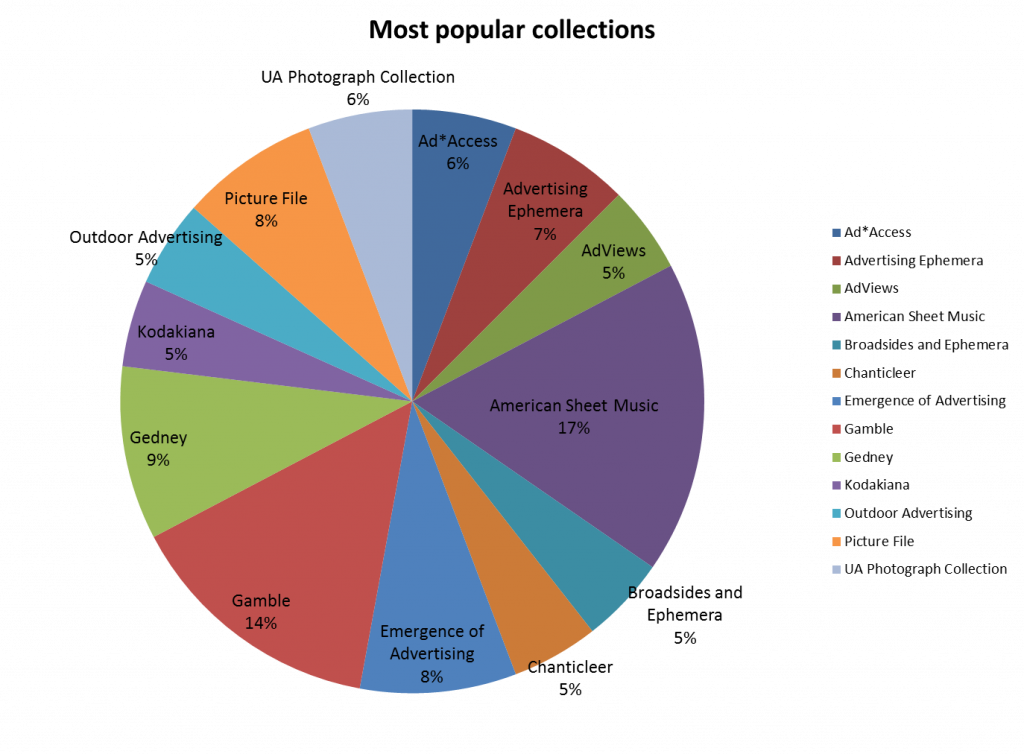

What I do at the Library: Still figuring it out 🙂 The plan is to collect, analyze, and document data useful for evaluating library operations and understanding user needs; support data management, analysis, and reporting needs across the Libraries; and coordinate and deliver training on evaluation, data, and reporting tools. I’m here to help you, so get in touch!

I think Assessment and User Experience matters in the life of the Duke community because they help us to continuously monitor the Libraries’ impact and effectiveness, provide an ongoing basis to improve resources and services, and support data-informed management and decision making.

On the most unexpected trip I ever took, I was living in Germany as an exchange student in April 2005. A friend and I found cheap tickets to Rome and decided to take a vacation. The day after we bought our tickets Pope John Paul II passed away. We ended up in Rome during the Pope’s funeral, along with tens of thousands of pilgrims from all over the world. It was a really unexpected and interesting experience!

If I could take a month to intensively learn one new thing it would be wilderness survival skills, just in case (zombie apocalypse, etc.).

What I am currently reading for pleasure: The Broken Eye, by Brent Weeks and Our Separate Ways: Women and the Black Freedom Movement in Durham, North Carolina, by Christina Greene.

Thomas Crichlow

Position: Assessment and User Experience Project Manager

Length of time at Duke: a little over ten years, depending on how you count.

What I do at the Library:

- I plan and manage projects to create and renovate websites at Duke University Libraries.

- I lead project teams and also work as a web developer.

- I participate in assessments of how our community uses our websites, paying special attention to places where our patrons encounter difficulty in using our sites.

- As a member of our Web Experience Team (WebX), I foster discussions about our vision, strategy and priorities for meeting patron needs through our online presence.

I think Assessment and User Experience matters in the life of the Duke community because we are well positioned to take a collaborative approach in identifying and eliminating pain points that hinder our research community’s ability to use the many tools and services provided through Duke Libraries.

On the most unexpected trip I ever took, I walked a dog from Germany to France, but there and back again only took 45 minutes. I was a high school exchange student in Germany, and the family I stayed with lived near the border with France, which was only two farm fields away from their house. When we got to the border, one of the men staffing the border crossing filled a bowl of water for the dog whom they already seemed to be well acquainted with.

If I could take a month to intensively learn one new thing it would be something hands-on and creative like painting or drawing.

Something memorable that I never expected to see at Duke was a little cabin high-up within the bell tower at Duke Chapel from which Sam Hammond plays the carillon, a manually operated, 50-bell instrument. I worked at the Chapel at that time and had access to parts of it that aren’t normally open to the public. I appreciated Sam’s graciousness in letting me take a peek at this rarely viewed, but oft heard part of our University. A recent Duke Chronicle article provides a further glimpse via an interview with Mr. Hammond and a photo gallery. There is also a recording of “God rest ye merry, gentlemen” played on the carillon.

What I am currently reading for pleasure: Guards! Guards! which is part of the satire-filled Discworld series by Terry Pratchett.