At Duke University Libraries (DUL), we are embarking on a new way to propose digitization projects. This isn’t a spur of the moment New Year’s resolution I promise, but has been in the works for months. Our goal in making a change to our proposal process is twofold: first, we want to focus our resources on specific types of projects, and second, we want to make our efforts as efficient as possible.

Introducing Digitization Initiatives

The new proposal workflow centers on what we are calling “digitization initiatives.” These are groups of digitization projects that relate to a specific theme or characteristic. DUL’s Advisory Council for Digital Collections develops guidelines for an initiative, and will then issue a call for proposals to the library. Once the call has been issued, library staff can submit proposals on or before one of two deadlines over a 6 month period. Following submission, proposals will be vetted, and accepted proposals will move onto implementation. Our previous system did not include deadlines, and proposals were asked to demonstrate broad strategic importance only.

DUL is issuing our first call for proposals now, and if this system proves successful we will develop a second digitization initiative to be announced in 2018.

I’ll say more about why we are embarking on this new system later, but first I would like to tell you about our first digitization initiative.

Call for Proposals

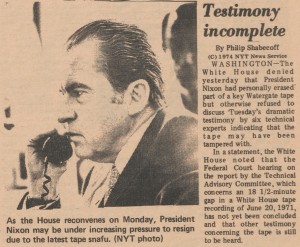

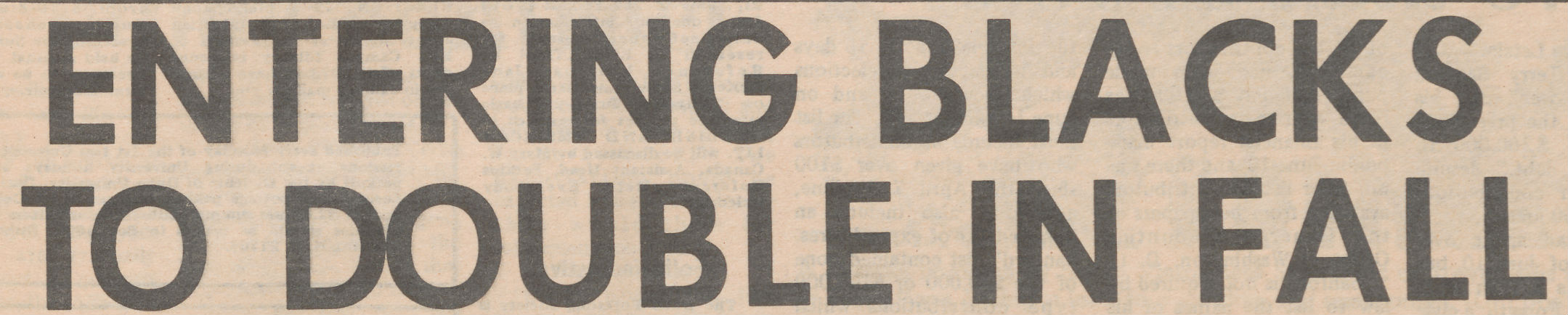

Duke University Libraries’ Advisory Council for Digital Collections has chosen diversity and inclusion as the theme of our first digitization initiative. This initiative draws on areas of strategic importance both for DUL (as noted in the 2016 strategic plan) and the University. Prospective champions are invited to think broadly about definitions of diversity and inclusion and how particular collections embody these concepts, which may include but is not limited to topics of race, religion, class, ability, socioeconomic status, gender, political beliefs, sexuality, age, and nation of origin.

Full details of the call for proposals here: https://duke.box.com/s/vvftxcqy9qmhtfcxdnrqdm5kqxh1zc6t

Proposals will be due on March 15, 2017 or June 15, 2017.

Proposing non-diversity and inclusion related proposal

We have not forgotten about all the important digitization proposals that support faculty, important campus or off campus partnerships, and special events. In our experience, these are often small projects and do not require a lot of extra conservation, technical services, or metadata support so we are creating an“easy” project pipeline. This will be a more light-weight process that will still requires a proposal, but less strategic vetting at the outset. There will be more details coming out in late January or February on these projects so stay tuned.

Why this change?

I mentioned above that we are moving to this new system to meet two goals. First, this new system will allow us to focus proposal and vetting resources on projects that meet a specific strategic goal as articulated by an initiative’s guidelines. Additionally, over the last few years we have received a huge variety of proposals: some are small “no brainer” type proposals while others are extremely large and complicated. We only had one system for proposing and reviewing all proposals, and sometimes it seemed like too much process and sometimes too little. In other words one process size does not not fit all. By dividing our process into strategically focussed proposals on the one hand and easy projects on the other, we can spend more of our Advisory committee’s time on proposals that need it and get the smaller ones straight into the hands of the implementation team.

Another benefit of this process is that proposal deadlines will allow the implementation team to batch various aspects of our work (batching similar types of work makes it go faster). The deadlines will also allow us to better coordinate the digitization related work performed by other departments. I often find myself asking departments to fit digitization projects in with their already busy schedules, and it feels rushed and can create unnecessary stress. If the implementation team has a queue of projects to address, then we can schedule it well in advance.

I’m really excited to see this new process get off the ground, and I’m looking forward to seeing all the fantastic proposals that will result from the Diversity and Inclusion initiative!

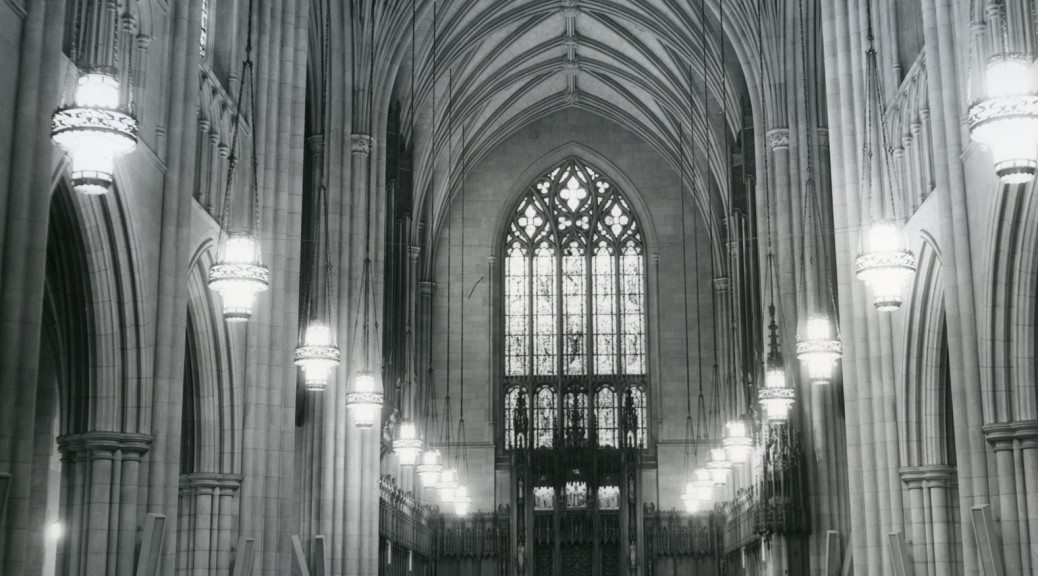

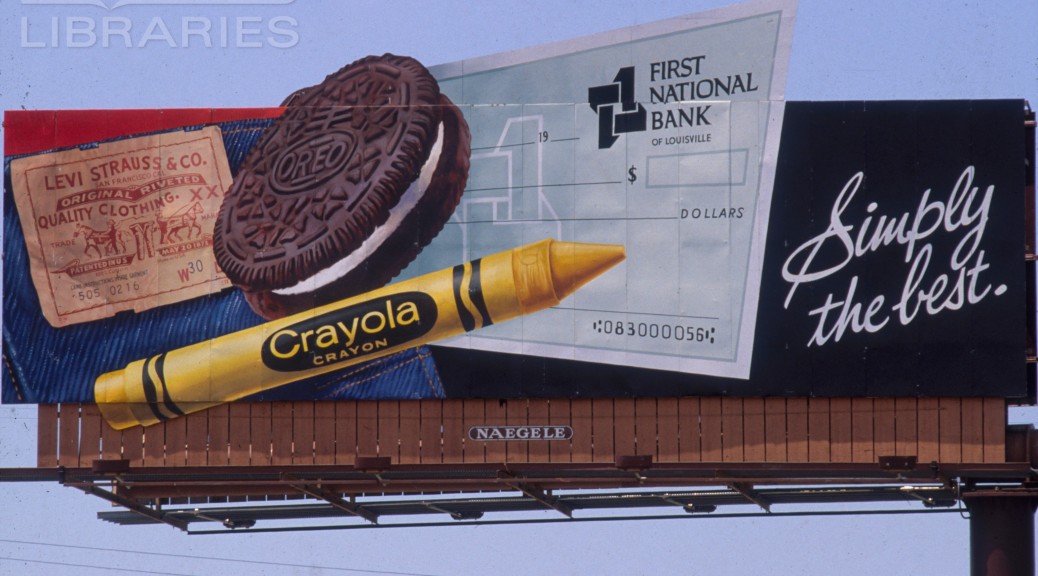

Digital Collections Promotional Card

Digital Collections Promotional Card