Duke Digital Repository is, among other things, a digital preservation platform and the locus of much of our work in that area. As such, we often ponder the big questions:

- What is the repository?

- What is digital preservation?

- How are we doing?

What is the repository?

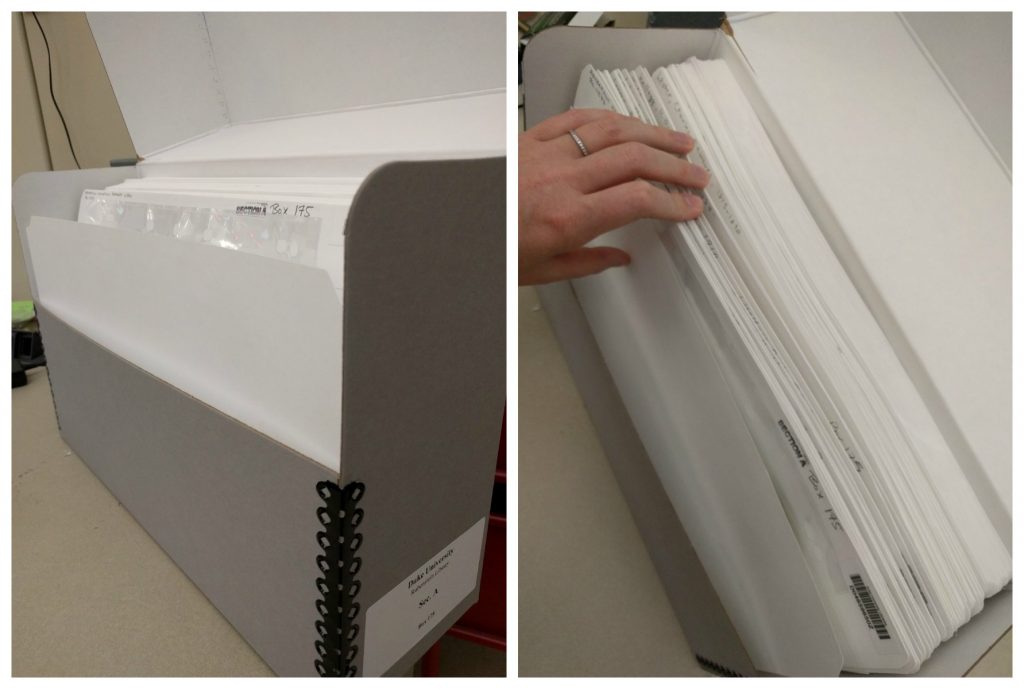

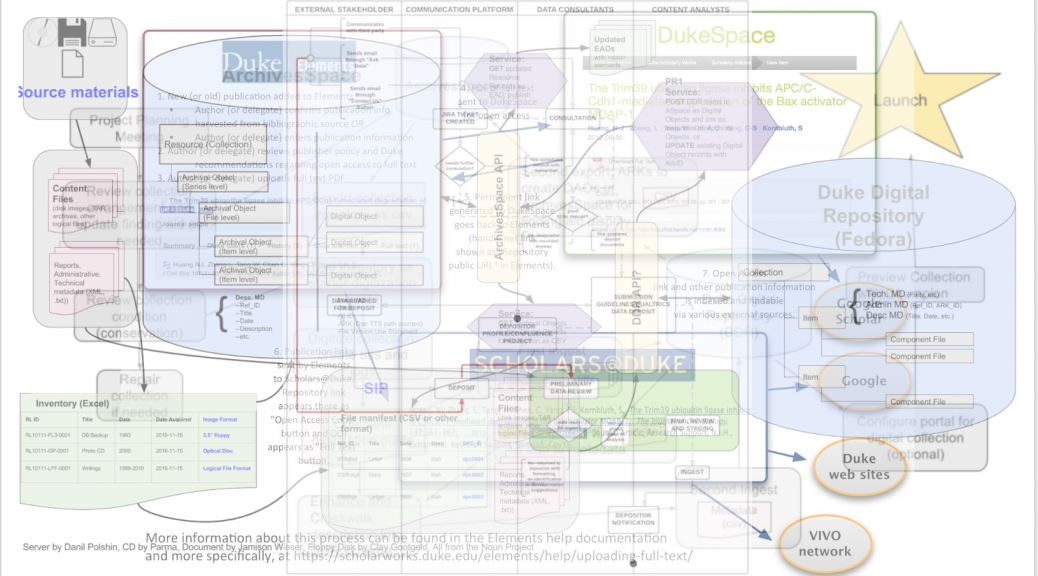

Fortunately, Ginny gave us a good start on defining the repository in Revisiting: What is the Repository? It’s software, hardware, and collaboration. It’s processes, policies, attention, and intention. While digital preservation is one of the focuses of the repository, digital preservation extends beyond the repository and should far outlive the repository.

What is digital preservation?

There are scores of definitions, but this Medium Definition from ALCTS is representative:

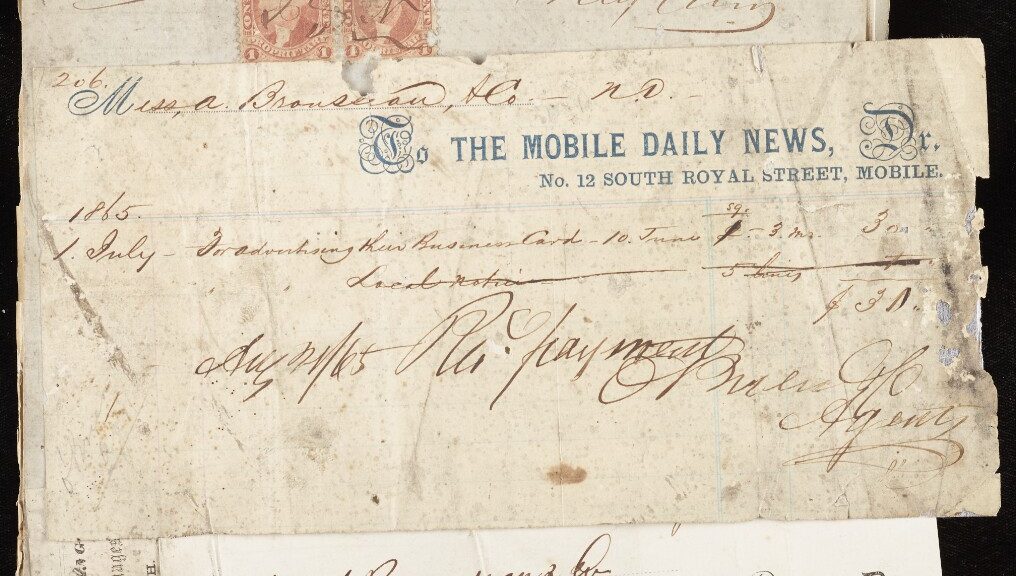

Digital preservation combines policies, strategies and actions to ensure access to reformatted and born digital content regardless of the challenges of media failure and technological change. The goal of digital preservation is the accurate rendering of authenticated content over time.

This is the short answer to the question: Accurate rendering of authenticated digital content over time. This is the motivation behind the work described in Preservation Architecture: Phase 2 – Moving Forward with Duke Digital Repository.

How are we doing?

There are 2 basic methodologies for assessing this work- reactive and proactive. A reactive approach to digital preservation might be characterized by “Hey! We haven’t lost anything yet!”, which is why we like the proactive approach.

Digital preservation can be be a pretty deep rabbit hole and it can be an expensive proposition to attempt to mitigate the long tail of risk. Fortunately, the community of practice has developed tools to assist in the planning and execution of trustworthy repositories. At Duke, we’ve got several years experience working in the framework of the Center for Research Libraries’ Trustworthy Repositories Audit & Certification: Criteria and Checklist (TRAC) as the primary assessment tool by which we measure our efforts. Much of the work to document our preservation environment and the supporting institutional commitment was focused on our DSpace repository, DukeSpace. A great deal has changed in the recent 3 years including significant growth in our team and scope. So, once again we’re working to measure ourselves against the standards of our profession and to use that process to inform our work.

There are 3 areas of focus in TRAC: Organizational Infrastructure, Digital Object Management, and Technologies, Technical Infrastructure, & Security. These cover a very wide and deep field and include things like:

- Securing Service Level of Agreements for all service providers

- Documenting the organizational commitments of both Duke University and Duke University Libraries and sustainability plans relating to the repository

- Creating and implementing routine testing of backup, remote replication, and restoration of data and relevant infrastructure

- Creating and approving documentation on a wide variety of subjects for internal and external audiences

Back to the question: How are we doing?

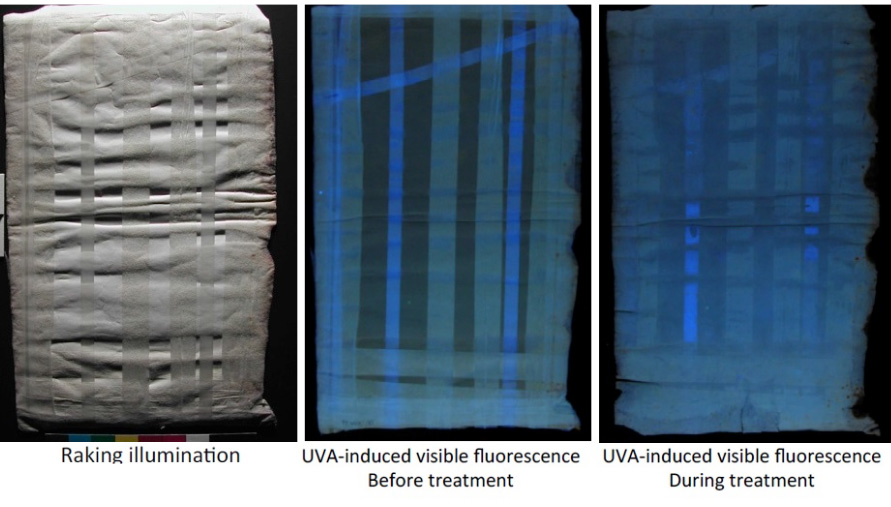

Well, we’re making progress! Naturally we’re starting with ensuring the basic needs are met first- successfully preserving the bits, maximizing transparency and external validation that we’re not losing the bits, and working on a sustainable, scalable architecture. We have a lot of work ahead of us, of course. The boxes in the illustration are all the same size, but the work they represent is not. For example, the Disaster Recovery Plan at Hathi Trust is 61 pages of highly detailed thoughtfulness. However, these works build on each other so we’re confident that the work we’re doing on the supporting bodies of policy, procedure, and documentation will make ease the work to a complete Disaster Recovery Plan.