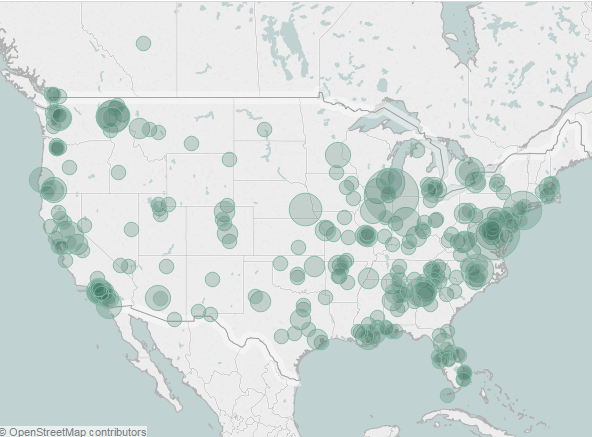

When Angier B. Duke (1884-1923) and Mary L. Duke (Biddle) (1887-1960) were born, Trinity College was still plodding away in Randolph County, and the American Tobacco Company was just a twinkle in James B. Duke’s eye. Still, W. Duke, Sons, and Company, the family business founded by Washington Duke, was so successful that parents Benjamin N. and Sarah P. Duke could already afford to give their son and daughter a childhood that wildly exceeded that of previous generations in terms of comfort and education. The couple’s first son, George Washington Duke, died at about two or three years of age in the early 1880s. His life preceded the time span of most of the papers held by the Rubenstein Library, and only a few reminders of his brief existence can be found, such as the haunting note from Ken Roney, Ben’s uncle, following the death of Roney’s son: “You know and I know now, how hard it is to give up a promising son.” Given this tragic past, the couple’s second and third children were much doted upon by their parents.

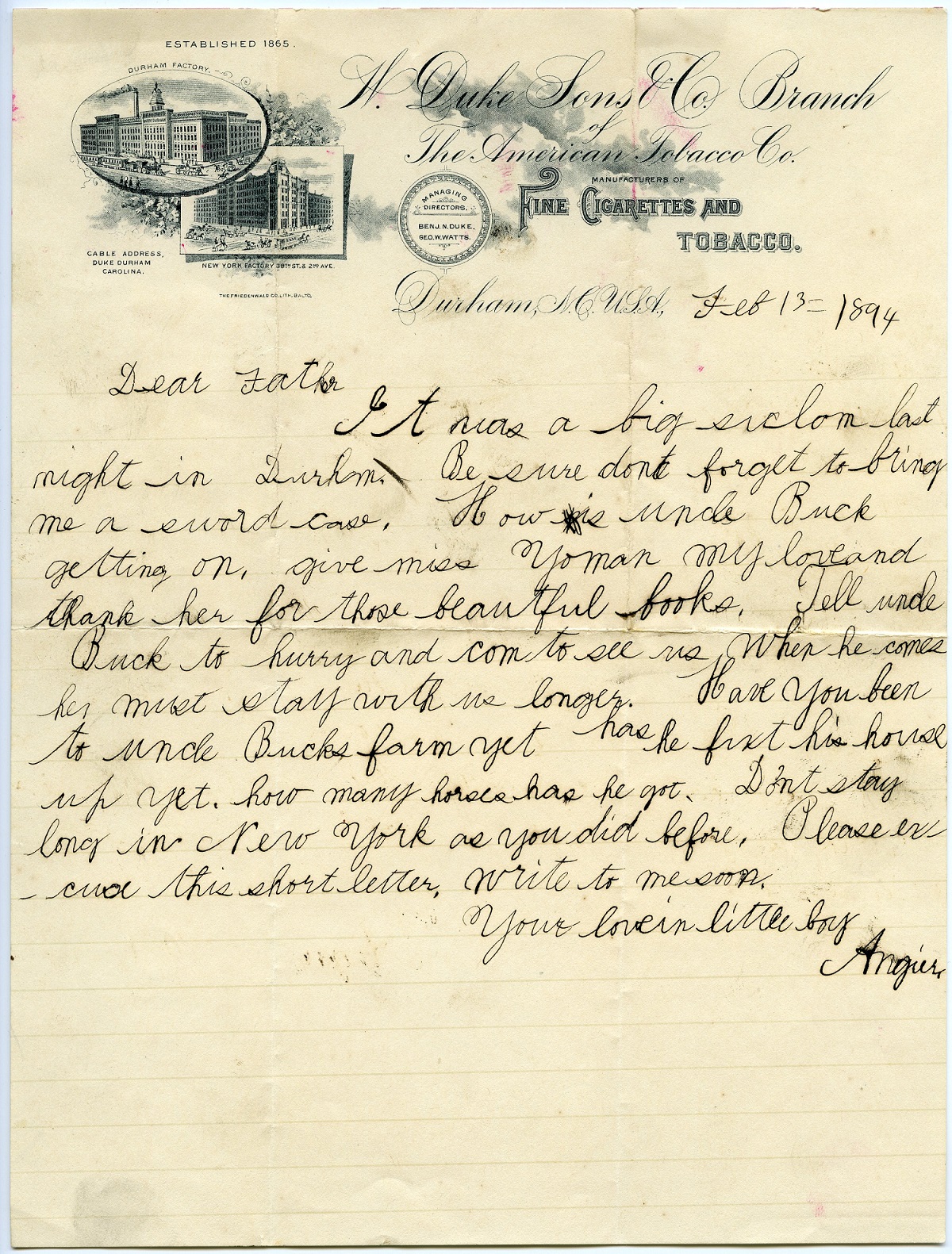

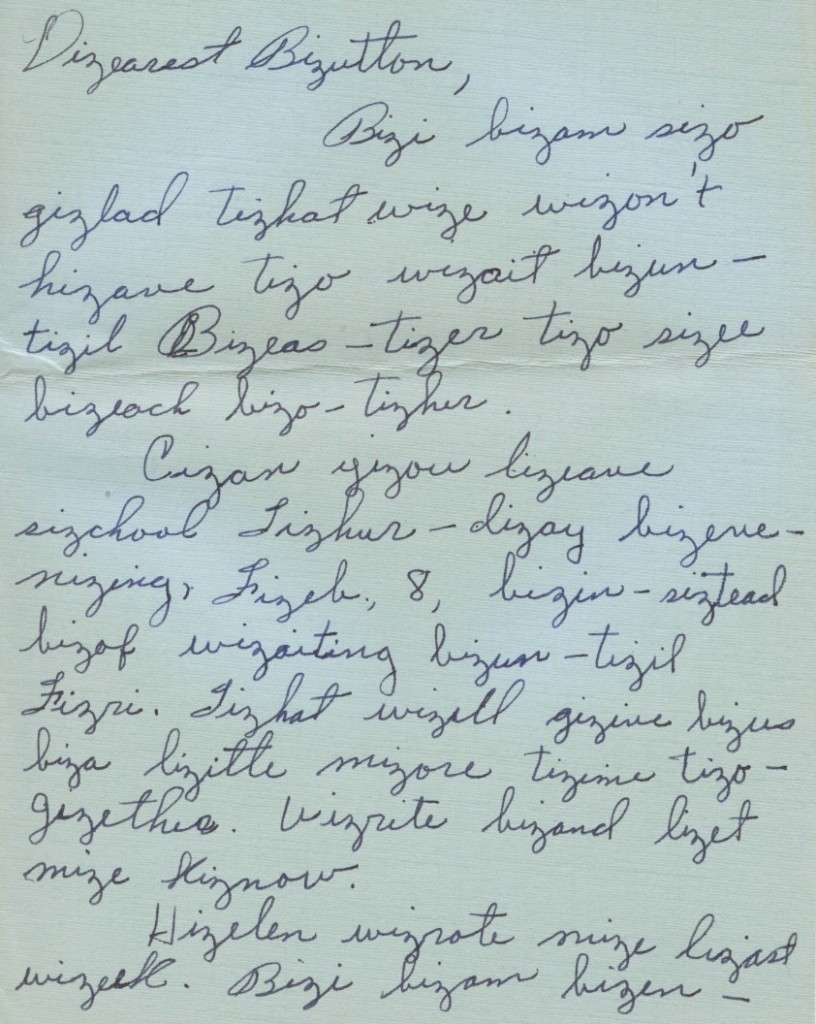

Among the few remaining mementos of their childhoods in the Benjamin Duke papers, some of the most amusing are the letters the children wrote to their father when he was away on business in New York. A young Angier was full of demands—for a sword case, a pair of shoes, and a visit from “Uncle Buck”: “when he comes he must stay with us longer.”

In 1893 he also sent along his first school composition, an essay on Christopher Columbus (historical myths intact). Mary delighted in telling her father of her April Fools’ Day pranks:

“I have had a right good time April fooling people. I fooled Mrs. Robinson, and brother, and many other people. I don’t think you can fool anybody much up there.”

While the ties between the Duke family and Trinity College were obviously very strong (“Duke University,” need I say more?), it still seems extraordinary how closely connected Angier and Mary were with the campus community from a young age. A steady stream of professors were welcomed at the Duke home, including former presidents Crowell, Kilgo, Few, and many other names you might be able to pick off a university building in passing. Sarah P. Duke hosted literary societies such as the Shakespeare Club, and guest speakers also lodged at the Duke home. Angier and Mary’s private tutor was Arthur H. Meritt, whose day job was professor of Latin, German, and Greek.

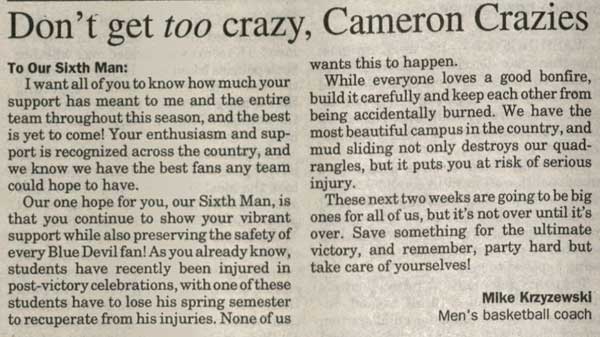

Community events also drew together the Dukes and other Durham residents with the college faculty, including spelling bees and athletic matches. An 1896 letter from Angier to his father conveys his enthusiasm for an upcoming “kite-sailing” contest to be held by Professors Lockwood and Meritt. The same Professor Lockwood (physics and biology) used a nine-year old Mary, or rather four Mary’s, as the subject of one of his trick photograph experiments.

When the time came for Angier and Mary to attend college—well, it’s safe to say that Carolina wasn’t on the table. By the time they began their respective terms at Trinity (Angier in 1901 and Mary in 1903), the siblings already had buildings named after them, built with funds from their father and grandfather. The Mary Duke Women’s Building was demolished long ago to make way for new dormitories, while the Angier B. Duke Gymnasium, better known by the nickname “The Ark,” still stands on Duke University’s East Campus.

While the siblings lived in New York after they graduated, they always maintained a connection to Durham and their alma mater. Angier served on the Trinity College Board of Trustees, was president of the Trinity Alumni Association, contributed to the construction of the first fraternity dwellings sanctioned by the college, and left a generous bequest in his will, which was executed after his untimely death in 1923. He and Mary both donated considerable sums to realize the completion of the Alumni Memorial Gymnasium, built in honor of the students and alumni who perished during World War I. Perhaps the greatest testaments to Mary Duke Biddle’s philanthropy are the Sarah P. Duke Gardens and her support of the arts through the Mary Duke Biddle Foundation. Like their parents, uncle and grandfather, both Angier and Mary succeeded in leaving a mark on the institution that had truly become part of the family.