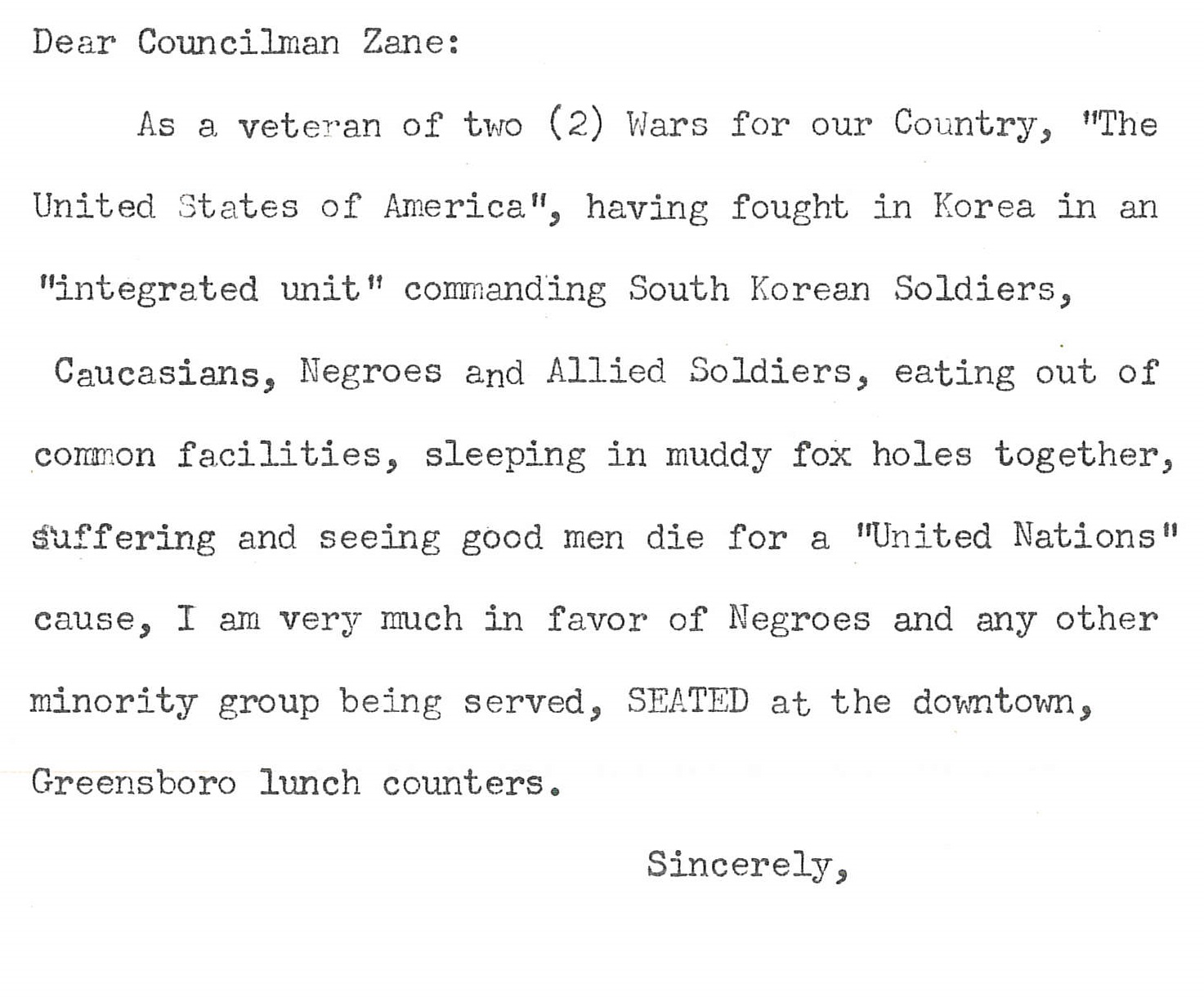

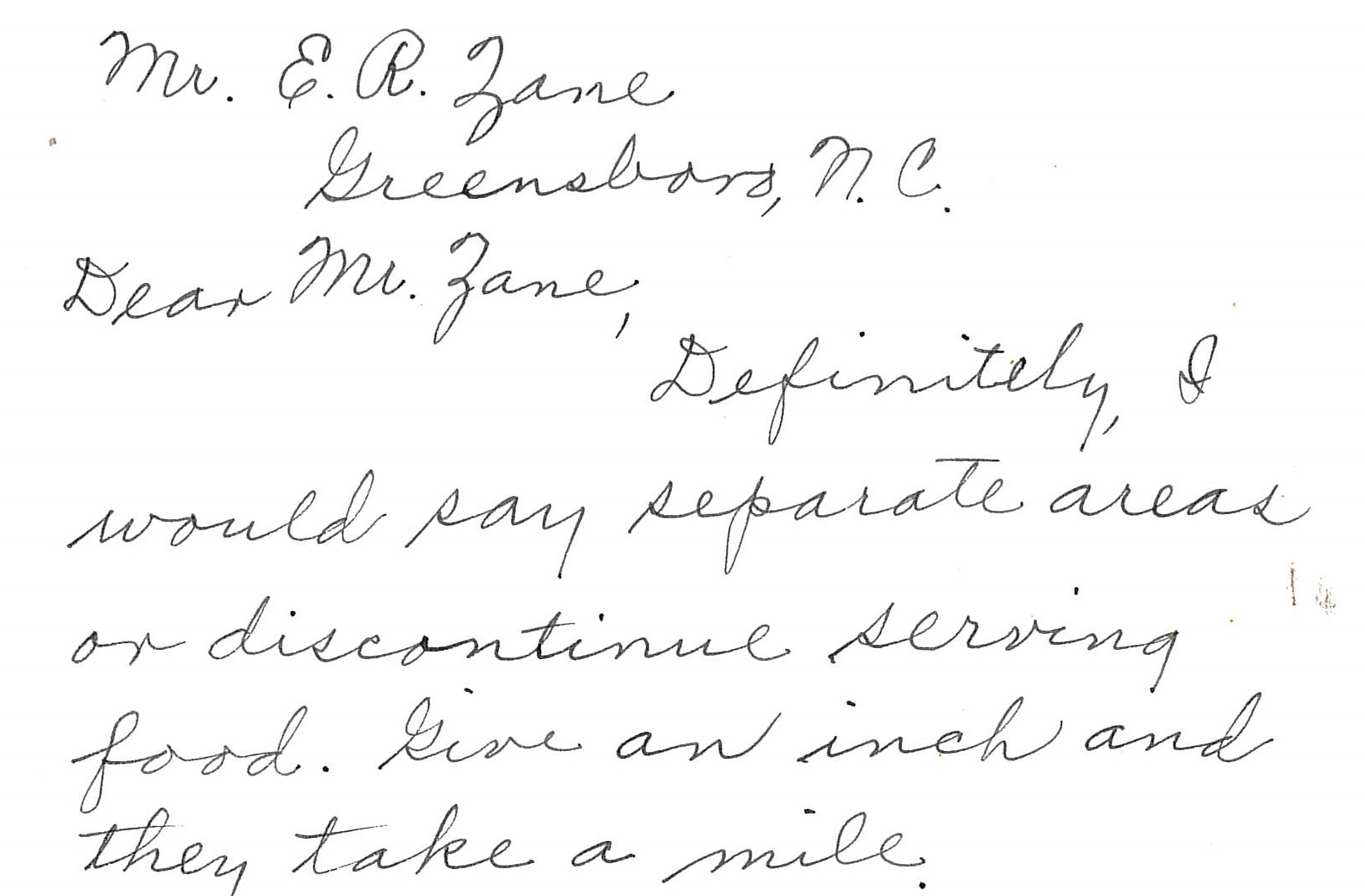

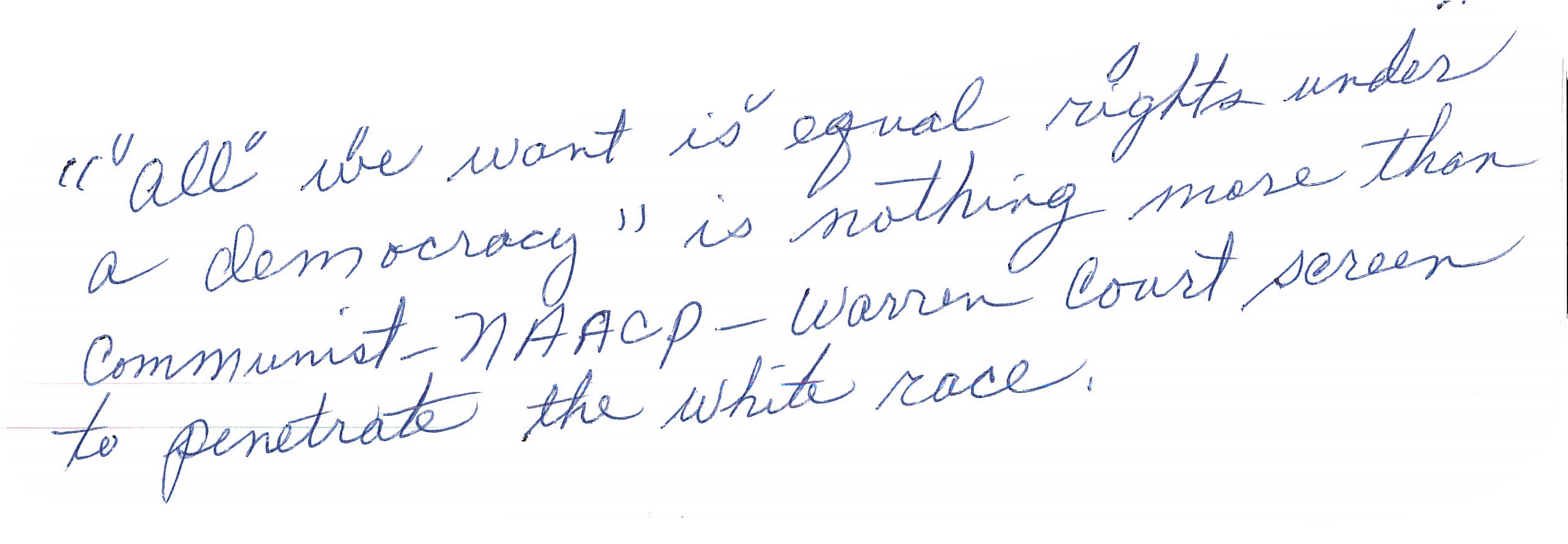

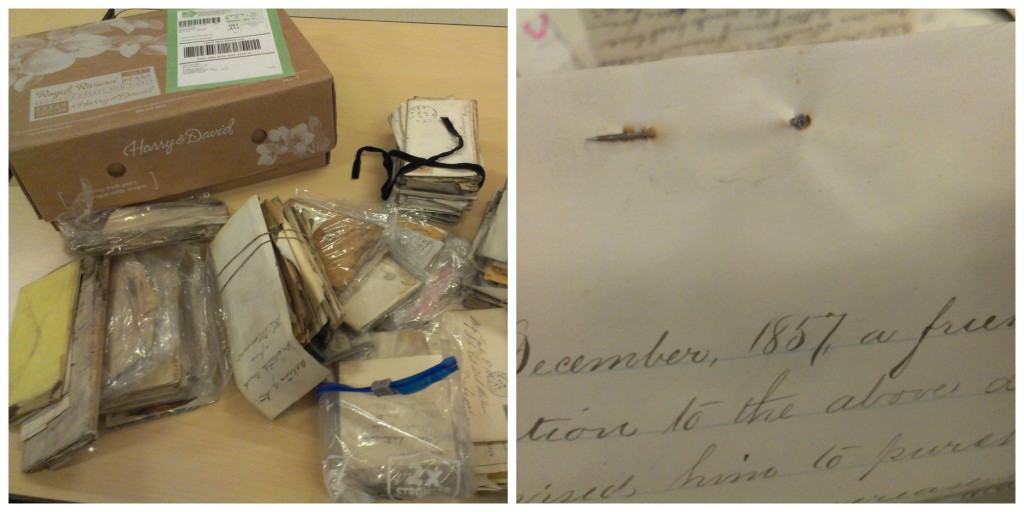

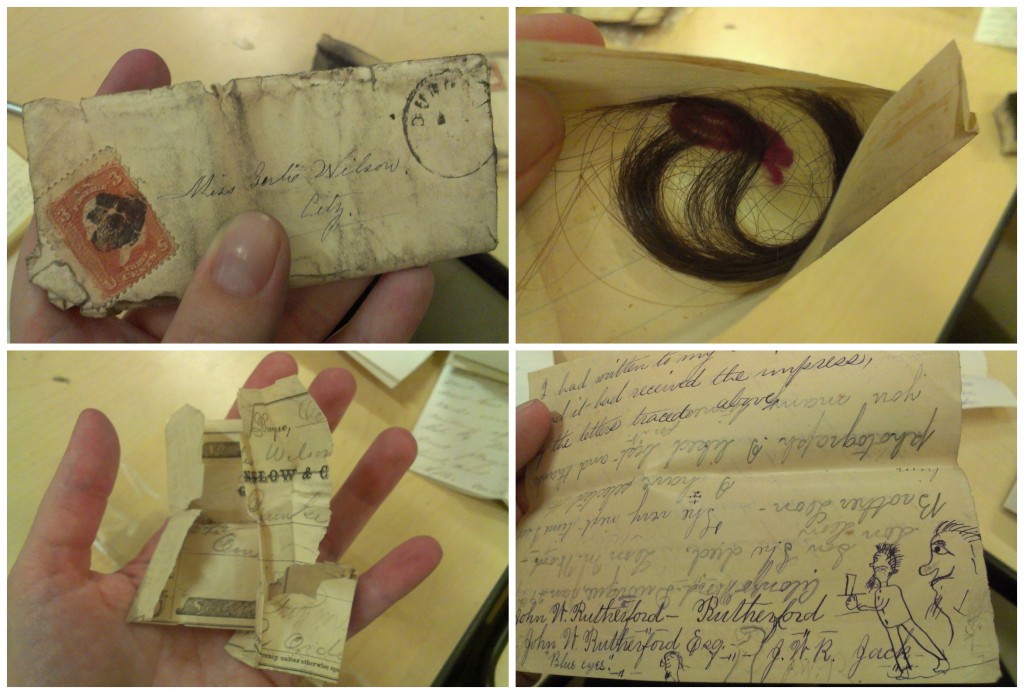

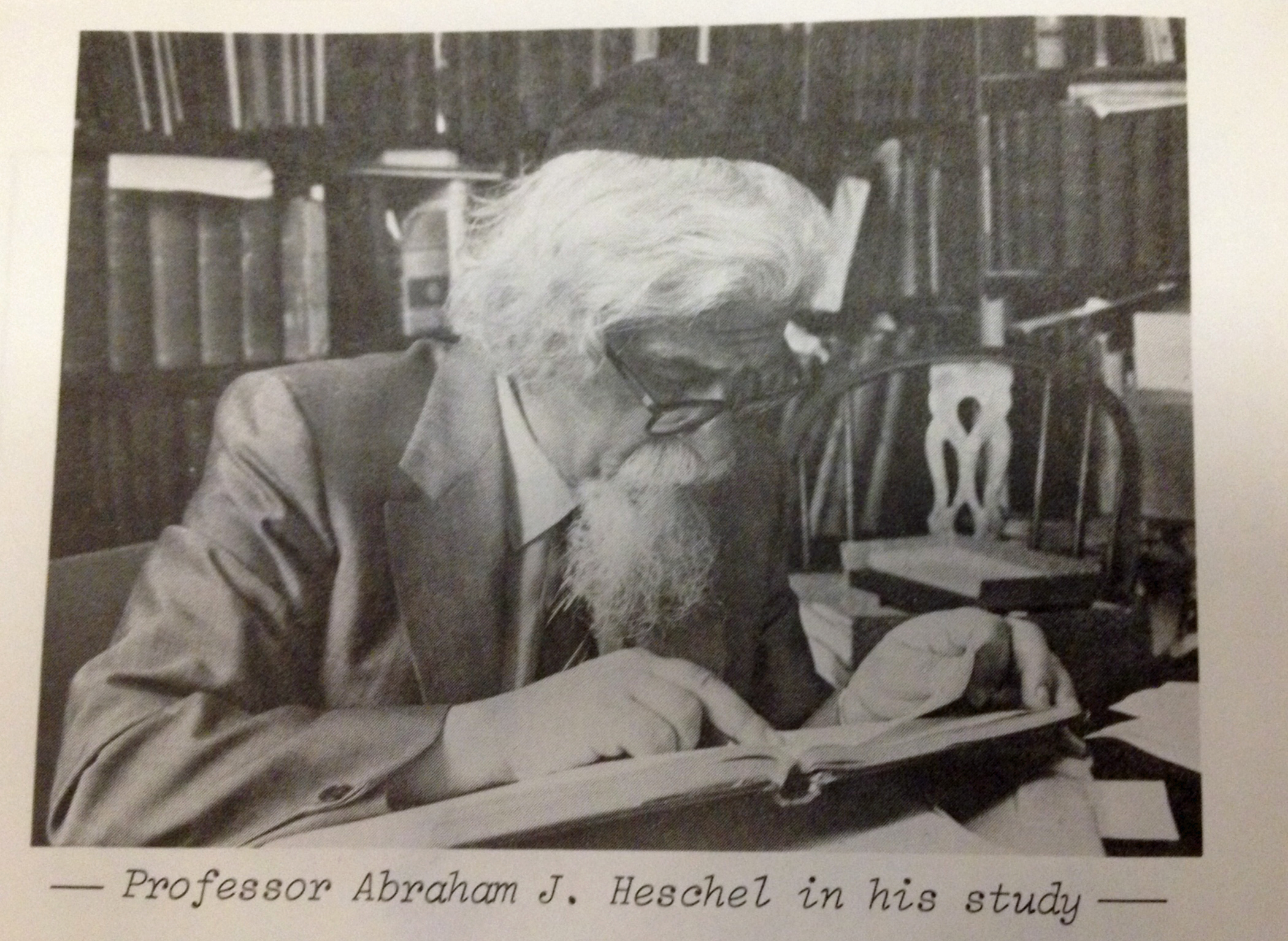

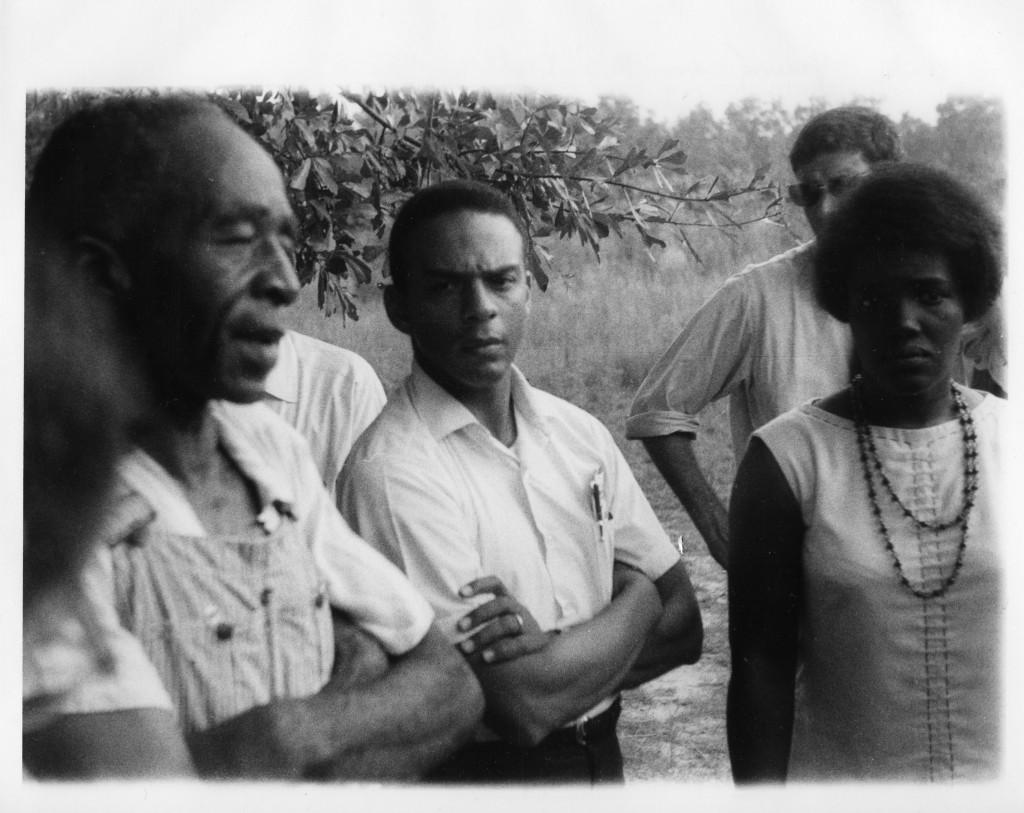

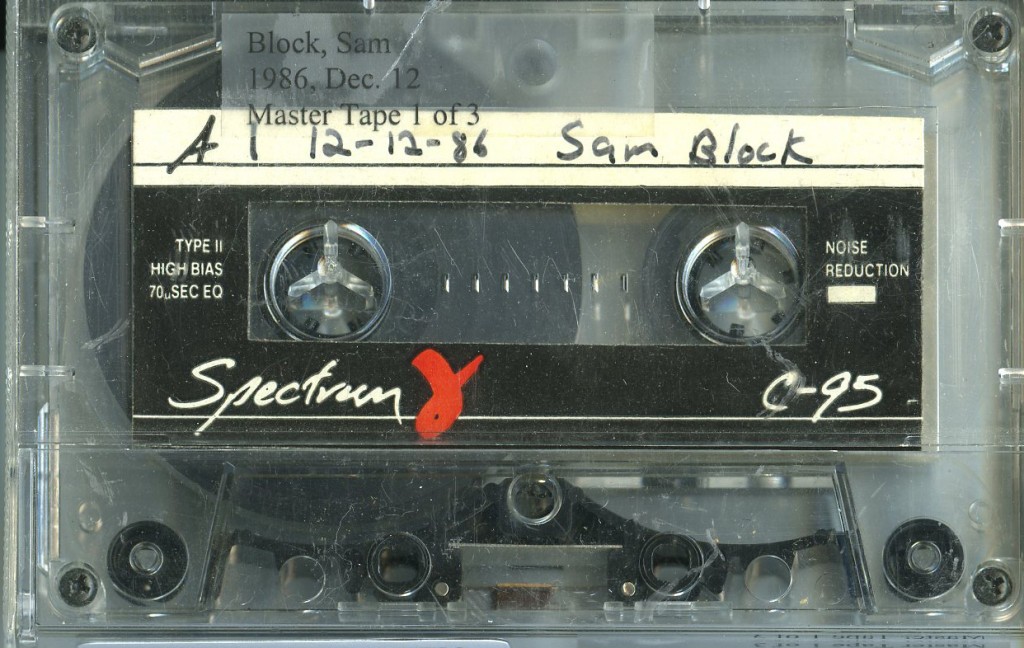

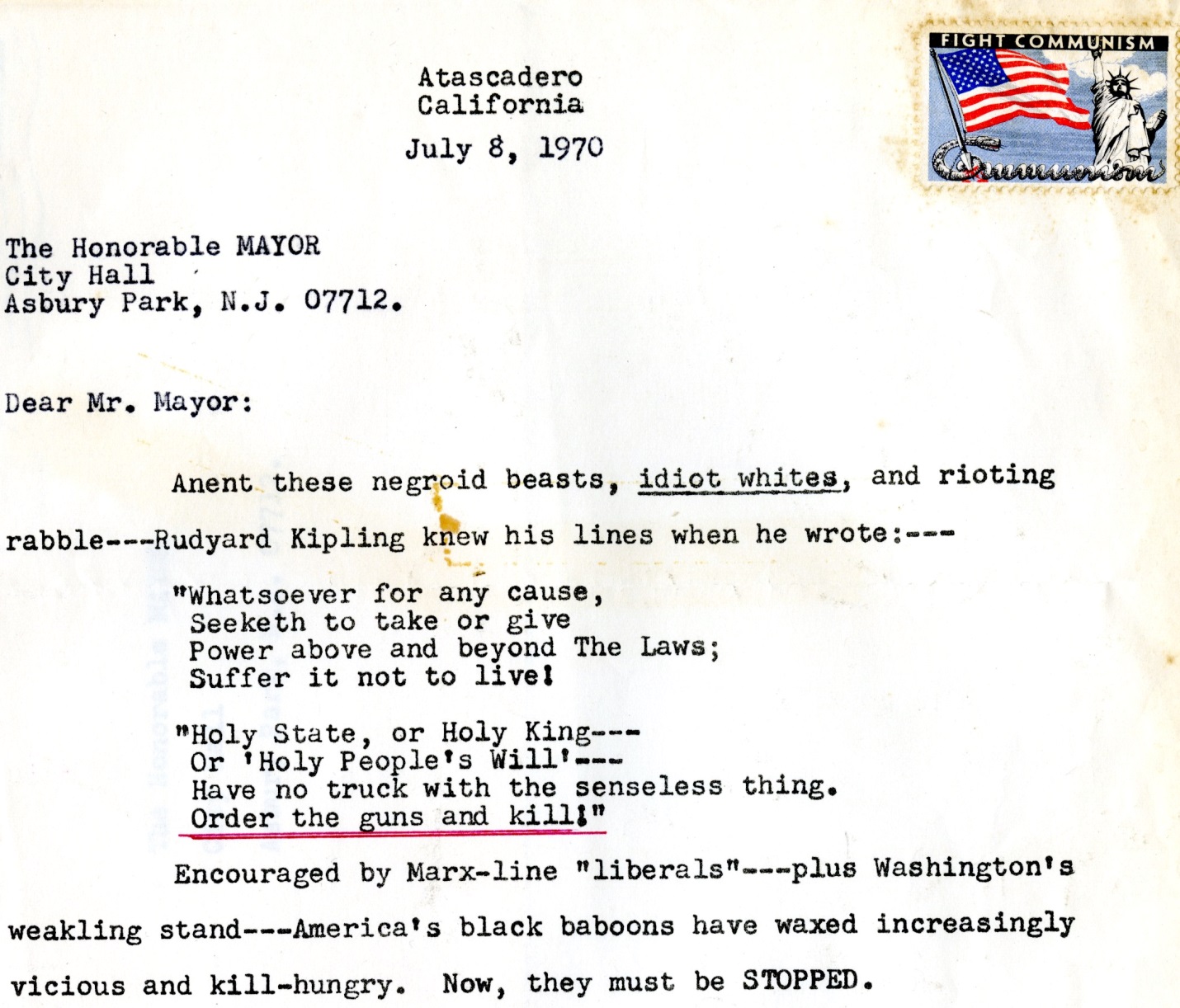

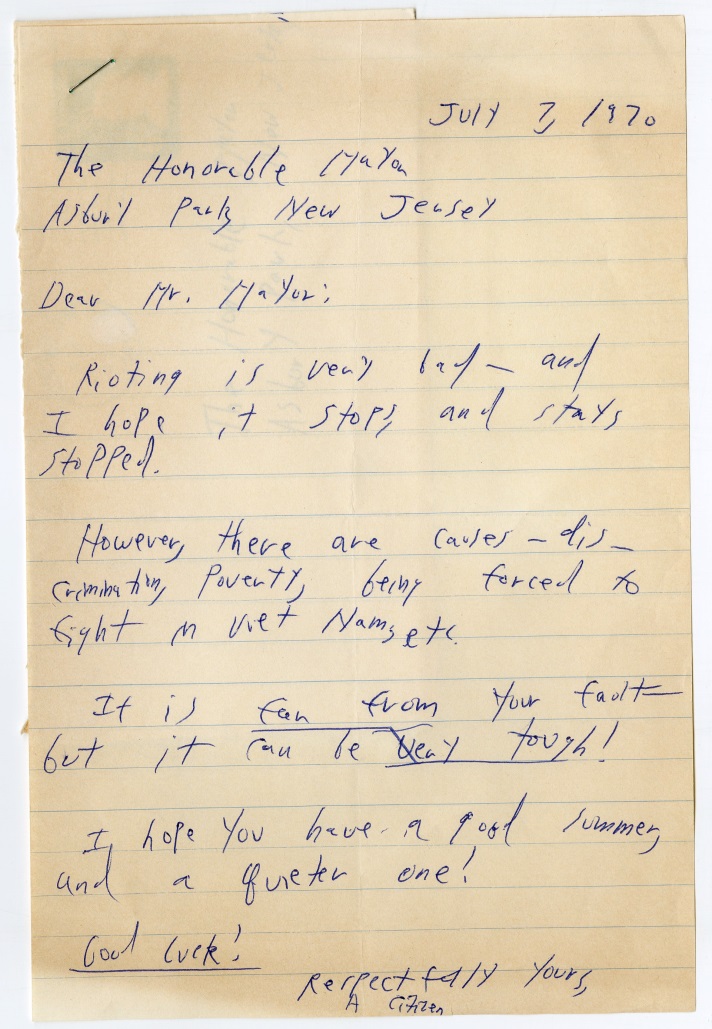

The John Hope Franklin Research Center for African and African American History and Culture recently acquired the Joseph F. Mattice Papers. Mattice was a native of Asbury Park who served as a lawyer, city council member, and district court judge prior to being elected mayor of Asbury Park, New Jersey in 1969. Mattice was mayor during the Asbury Park July 1970 riots and the collection contains a bevy of material related to the riots including letters from concerned citizens, business people, news clippings, and hate speech.

So how did Asbury Park become ground zero for riots from July 4th, 1970 to July 10th, 1970? This story began way before 1970. The first wave of the Great Migration brought African Americans from the South to Asbury Park for better opportunities. Historically, Asbury Park was a resort town that recruited African Americans to work in the resort industry.

At the time of the riots, Asbury Park was a town of 17,000, 30% of which were African-American. The town’s population increased to 80,000 with summer vacationers. The Great Depression, followed by World War II, caused the resort industry in Asbury Park to change dramatically to keep up with the times. The fancy resort stays gave way to weekend vacationers. The community maintained a steady resort community, but jobs at the resorts were frequently outsourced to white youth in the surrounding areas instead of local African American youth, which caused frustration in the community.

On the evening of Saturday July 4, 1970 all of the tension due to the lack of jobs, recreational opportunities, and decent living conditions came to a head.

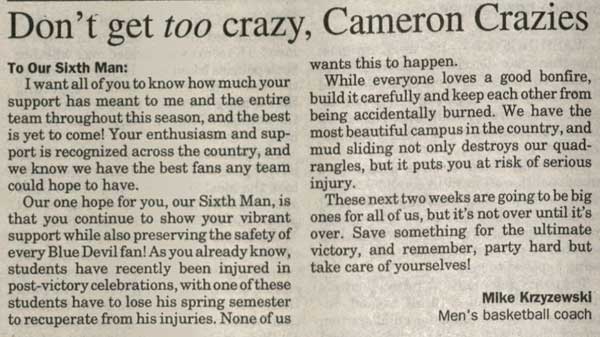

- By Monday July 6th, Mayor Mattice ordered a curfew. Surrounding local police as well as New Jersey state police were summoned and brought in via trucks by the National Guard.

- Tuesday July 7, 1970: African American community representatives presented a list of twenty demands to city officials including better housing conditions as many were infested with rats.

- Wednesday July 8, 1970: City officials, representatives of New Jersey Governor Cahill, and the African American community met in a closed conference. Governor Cahill completed a brief tour via vehicle then requested President Nixon to declare the city a major disaster area after the disorders (as the riots were called) were over.

- Friday July 10, 1970: marked the last day of rioting. The state troopers were removed from the West Side but remained on patrol of other sections of the city. Mattice and city council had a productive meeting with West Side residents to discuss demands.

In the end, over 180 people, including 15 state troopers were injured, and the shopping district of the west side neighborhood of Asbury Park was destroyed. Police made 167 arrests. Many West side residents were displaced from their homes, and the neighborhood was still in disarray five years after the riots. There was an estimated $4,000,000 in damage, and an additional $1,600,000 spent on cleanup costs.

The riots brought national attention to Asbury Park, New Jersey. However, Asbury Park was just one of many cities across the United States that experienced riots within the late 60s- early 70s period. The same issues: lack of job opportunities and unfit housing were prevalent for many African Americans. The riots forced America to look at the inequalities, acknowledge them and work towards making things better.

The Joseph F. Mattice papers give an insider view into the riots and this period in general. The collection is a vital research tool that allows the reader to make their own interpretation of this historical event.

Post contributed by Charmaine Bonner, SNCC Collections Intern.