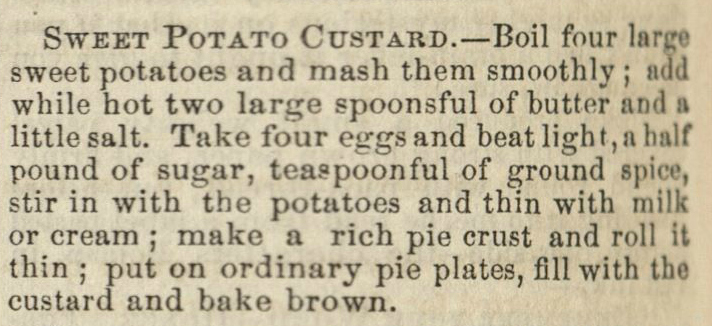

For this week’s test kitchen, I made a Sweet Potato Custard from a recipe in the November 1870 issue of The Rural Carolinian. The Rural Carolinian was “An Illustrated Magazine of Agriculture, Horticulture, and the Arts” published out of Charleston, South Carolina that provided advice and information on a number of topics that would have been of interest to farmers. Other articles in this issue include “How to Utilize Forest Leaves,” “Prickly Pear or Cactus,” and “How to Prune a Peach Tree” as well as more general interest reading such as “Anesthesia — What Is It? And to Whom are we Indebted for it?”

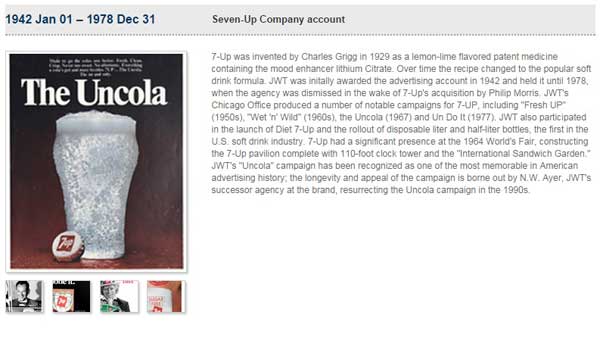

For this week’s test kitchen, I made a Sweet Potato Custard from a recipe in the November 1870 issue of The Rural Carolinian. The Rural Carolinian was “An Illustrated Magazine of Agriculture, Horticulture, and the Arts” published out of Charleston, South Carolina that provided advice and information on a number of topics that would have been of interest to farmers. Other articles in this issue include “How to Utilize Forest Leaves,” “Prickly Pear or Cactus,” and “How to Prune a Peach Tree” as well as more general interest reading such as “Anesthesia — What Is It? And to Whom are we Indebted for it?”

Each issue of The Rural Carolinian also included recipes, part of the magazine’s “Literary and Home Department,” which was intended to appeal to women, broadening the magazine’s audience. They sought submissions from women, asking them “Will not our dear friends, the ladies, interest themselves in our behalf and help us to make this department an attractive feature of The Rural Carolinian.” The recipes included aren’t necessarily what we think of as recipes, under recipes this issue has instructions on how to make “family glue” and lamp wicks. However, this is in line with the older sense of the word which encompasses any “statement of the ingredients and procedure required for making something,” per the Oxford English Dictionary.

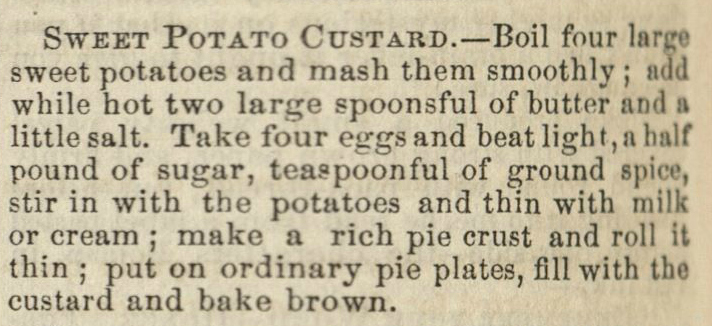

When I originally saw this recipe, I was interested, thinking, “I’ve never had sweet potato custard before!” Especially next to recipes like family glue, pumpkin chips, and apple water, it seemed unusual and intriguing. I didn’t read the recipe all the way through at first, and I missed the part where you put it in a pie crust, making it a not-so exotic sweet potato pie. Even still, I wanted to see how it compared to our modern sweet potato pies.

Like a lot of pre-twentieth century recipes, the recipe is minimalist in its approach and doesn’t offer detailed directions. The recipe calls for four sweet potatoes, and I bought four originally, but I think the sweet potatoes sold at my farmers market are monsters compared to what was available in 1870, so I used only two of them.

The recipe didn’t specify what to do with them beyond boiling and mashing, so I peeled and cubed them first before tossing them in a pot of boiling water until they were soft, about twenty minutes. After that I added the “two large spoonsful of butter,” which I interpreted as just over two tablespoons of butter, as well as a little salt. Then I got to use my potato masher, which only gets used at Thanksgiving. This gave me two cups of mashed sweet potato, which ended up being enough to fill my pie and then some.

Next four eggs “beat light,” sugar, spice, and milk or cream are mixed in with the mashed sweet potatoes. As Aaron noted in his post about rice apples, the lack of specifics in a recipe would have allowed for flexibility and improvisation based around what you had in your pantry. I appreciated this when the recipe called for milk or cream to thin it out, since all I had in the house was half-and-half. But I was a little flummoxed by the “teaspoonful of ground spice” called for. Was this referring to some particular spice that if I were cooking in 1870 would have just known? As a good librarian, I did some more primary source research and looked at other recipes from the era. As far as I could tell “spice” didn’t mean any particular spice, and there wasn’t one spice that dominated recipes of this time period. Cinnamon, nutmeg, mace, and cloves all come up frequently. I settled on half a teaspoon of cinnamon and half a teaspoon of nutmeg which was a tasty choice, but I think any common spices would be good.

There was also the matter of a half-pound of sugar. Before Fannie Farmer popularized standard and level measurements of cups, tablespoons, and teaspoons in her 1896 Boston Cooking-School Cook Book, recipes offered looser measurements (hopefully your household cups and spoons were similar in size to the recipe author’s!) or if you were lucky weights. But I don’t have a scale and had to do a little converting. According to Farmer, one pound of sugar is equal to two cups, so I added a cup of sugar to my potato mixture.

After combining all this, it is to be poured into a “rich pie crust” that had been rolled thin and put in a pie plate. Interestingly, no pie crust recipe was offered, which makes me think the author thought everyone would have had a pie crust recipe at the ready. I went with a basic all-butter crust. Given the number of other recipes in The Rural Carolinian that call for lard, a crust with lard would have been more authentic, but I wanted my vegetarian friends to be able to partake.

The final direction is to “bake brown.” Grateful for a modern oven where I have the ability to set a temperature, I went with 350. I kept waiting for my pie to get “brown” and it never quite got there, so I took it out after an hour. This may have been a little too long; it did crack once it cooled. Next time, I’d check it at 45 minutes and if the center seemed cooked thoroughly, I wouldn’t worry about it getting brown.

Despite the slight overcooking, this was a very good sweet potato pie. There was nothing that distinguished it from any more modern sweet potato pies I’ve eaten though. I took a look at some modern recipes and they’re remarkably similar, though they usually have more butter and fewer eggs in them. I think I’ll actually fix this again for Thanksgiving, though I want to try pairing it with an ahistorical maple bourbon whipped cream.

Want to make history this Thanksgiving? Every Friday between now and Thanksgiving, we’ll be sharing a recipe from our collections that one of our staff members has found, prepared, and tasted. We’re excited to bring these recipes out of their archival boxes and into our kitchens (metaphorically, of course!), and we hope you’ll find some historical inspiration for your own Thanksgiving.

Post contributed by Kate Collins, Research Services Librarian

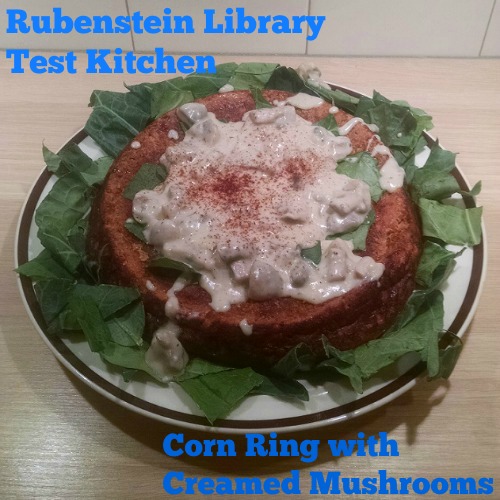

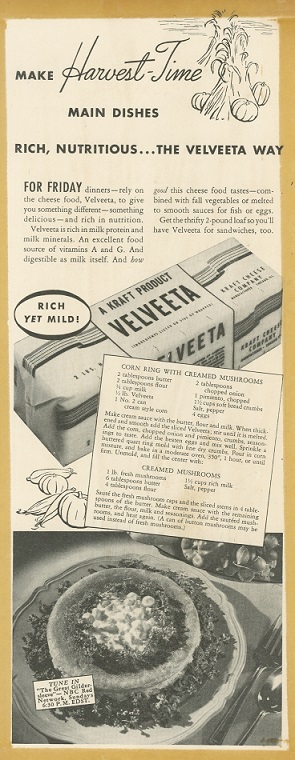

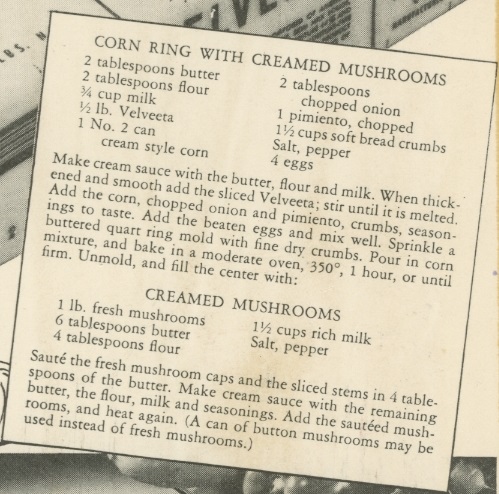

It’s an extremely simple recipe. I cooked up a cup of rice, opened a can of corn, browned a pound of ground beef, and threw everything together in a dish to bake for 20 minutes at 350. I thought I’d jazz up this plain casserole just a bit for my special guests, and added onions and a dash of ground cloves (a flavor sensation that I picked up from my own mom) to the meat, and threw a bunch of cheddar on top towards the end of its baking. When the dish was cooked, I also chopped up some parsley and chives from my porch for a tasty garnish. This was an easy and fast recipe to fix for a bunch of folks at a moment’s notice, and there could be endless improvisation depending on what you had on hand.

It’s an extremely simple recipe. I cooked up a cup of rice, opened a can of corn, browned a pound of ground beef, and threw everything together in a dish to bake for 20 minutes at 350. I thought I’d jazz up this plain casserole just a bit for my special guests, and added onions and a dash of ground cloves (a flavor sensation that I picked up from my own mom) to the meat, and threw a bunch of cheddar on top towards the end of its baking. When the dish was cooked, I also chopped up some parsley and chives from my porch for a tasty garnish. This was an easy and fast recipe to fix for a bunch of folks at a moment’s notice, and there could be endless improvisation depending on what you had on hand.