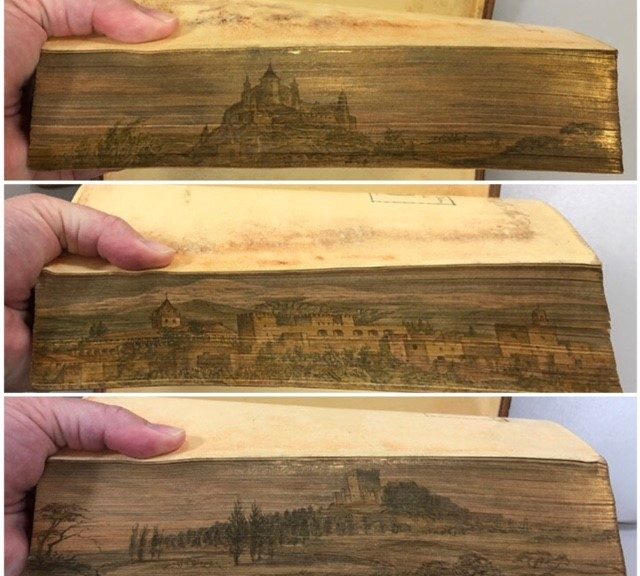

When you look at how books are generally made, you’ll find that a majority of them are either sewn with thread, glued together as individual sheets, or occasionally bound with a combination of sewing and commercial glue.

On rarer occasions, a book will be stapled together. As luck would have it, one of these books recently came across my bench in need of a new cover. At first glance, you can’t immediately tell the difference between a stapled book and a sewn book.

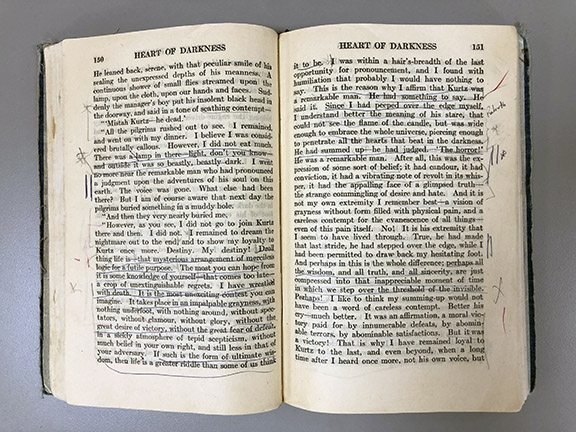

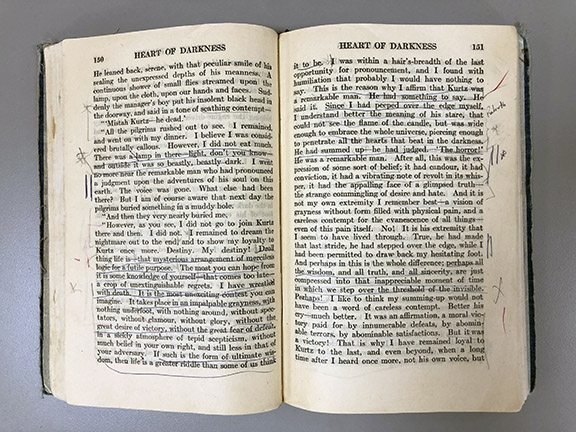

It’s not until you open the book up and look at the gutter of one of the signatures that you might be able to see whether the book is stapled or not.

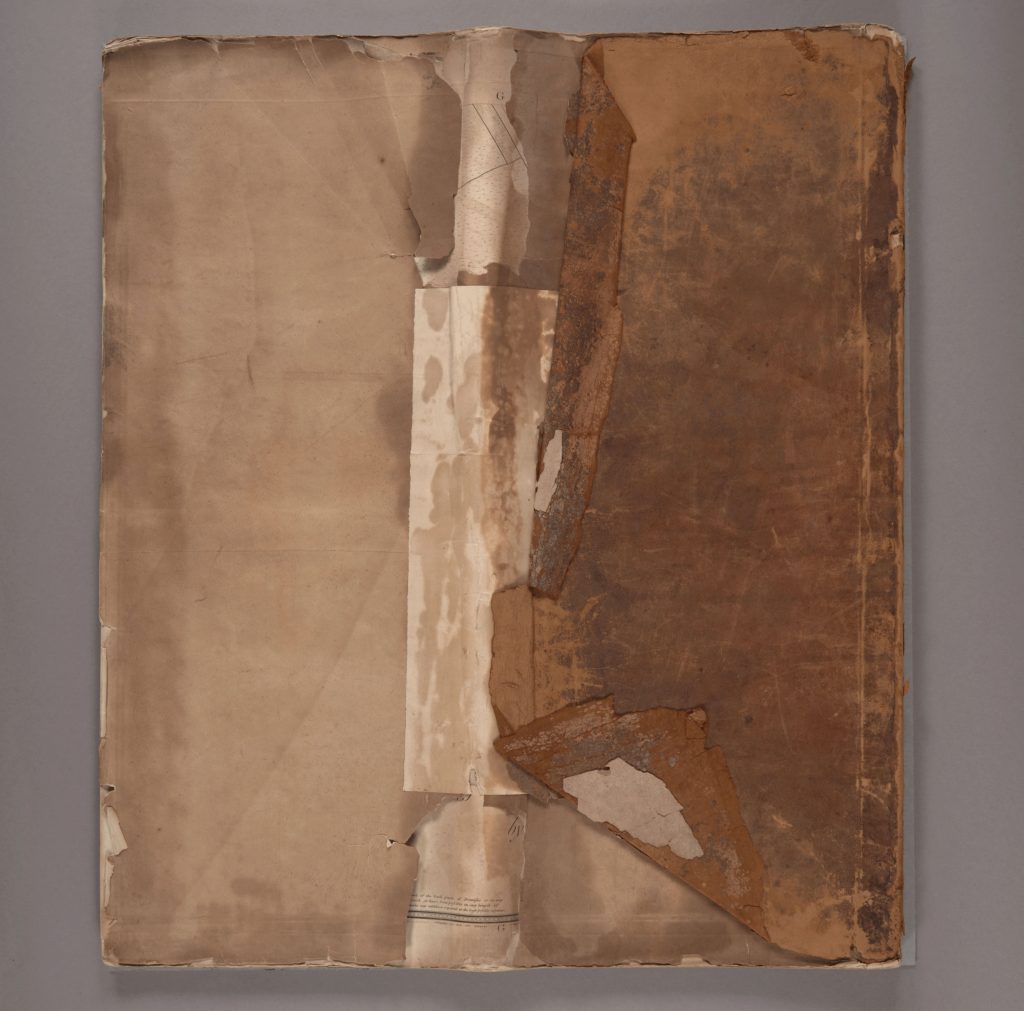

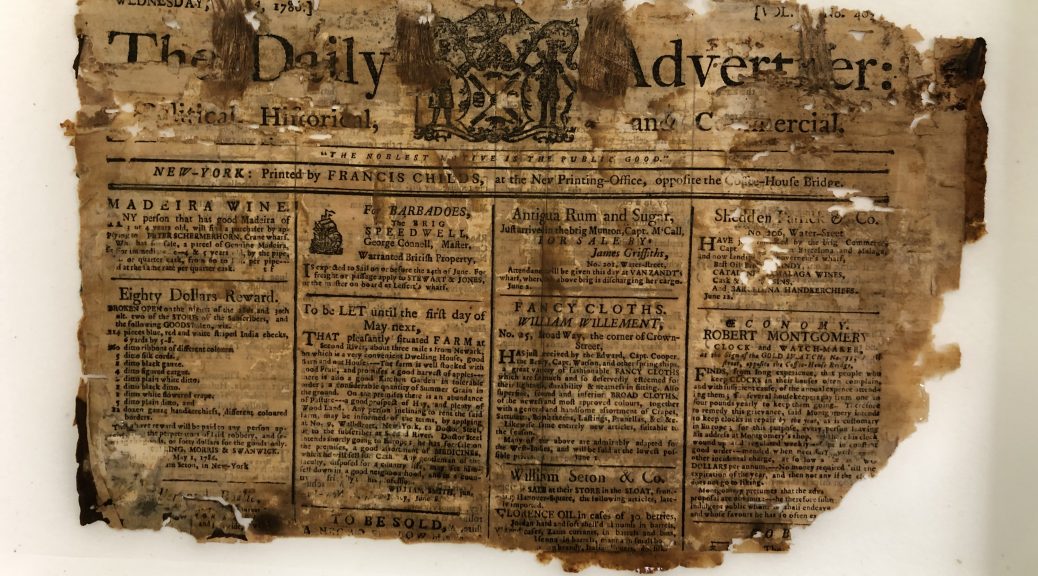

It’s even easier once you’ve taken the cover off and can look directly at the spine of the textblock. As you can see in the images below, there are staples running through a significant portion of the signatures of this book.

Now, in a perfect world where I have all the time and patience I could want, I might remove the staples, mend any damage to the signatures in the process, sew the book back together, and then make a new cover. In this case, such an approach would be too labor intensive and time consuming. As the only senior conservation technician charged with maintaining the general collections, I cannot devote that much time to one book when I might have as many as 25 other books also waiting to be treated.

Considerations

With binding structures like this, the treatment decisions tend to boil down to preserving the provenance of the object vs choosing to rebind the book for greater longevity. In this blog post by Peter D. Verheyen in 2011, it’s evident that these wire bindings are a curious part of the history of bookbinding. Since they’re unusual, and since our goal is to conserve as much of the original item as possible, one might think that saving the original binding would be the obvious choice.

But how do technicians in general collections conservation (such as myself) reconcile keeping as much of the original object intact when we also have to prioritize making sure that the book can withstand regular use from patrons? If the staples in the binding had been so rusted that they were breaking whenever I opened the book, I would most likely take a more involved approach to the treatment of this book. An example of such a treatment would be adhering a cotton cambric to the spine and sewing through it along with the textblock, which you can see an example of in this paper by our very own Beth Doyle.

Luckily, in this case, both the paper and the staples were in good enough condition that a secondary treatment wasn’t necessary. However, it could be argued that perhaps I should have gone ahead with the more complex treatment just in case the staples failed in the future. In the end, these are the dilemmas we face in general collections conservation.

Treatment

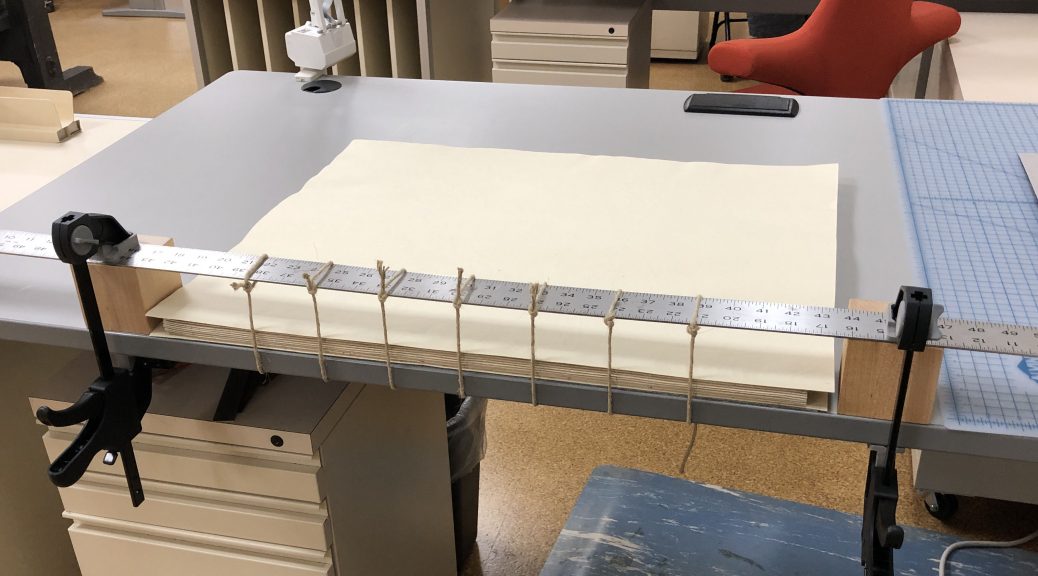

I decided that the best course of action would be to clean the spine of its original lining and glue and replace it with a strong Japanese tissue adhered with wheat starch paste. By doing so, the spine is stabilized and strengthened while the staples are also given additional support. This reduces the potential damage that could occur from future use and repeated opening and closing of the book.

With the textblock now in a stable state, I could prepare a new case for the book. The original case had already failed and since the original materials were too fragile to keep using, it didn’t make sense to try and reuse the case. Instead, I made an inset on the front board in order to preserve the original cover material. If you’d like to learn more about the book, you can find the catalog record here.