Two of the building’s elevator shafts are getting some renovations this week. Unfortunately they are right on the other side of the wall from the lab. So this is what it sounds like inside Beth’s office today:

So much for peace and quiet… TGIF!

Two of the building’s elevator shafts are getting some renovations this week. Unfortunately they are right on the other side of the wall from the lab. So this is what it sounds like inside Beth’s office today:

So much for peace and quiet… TGIF!

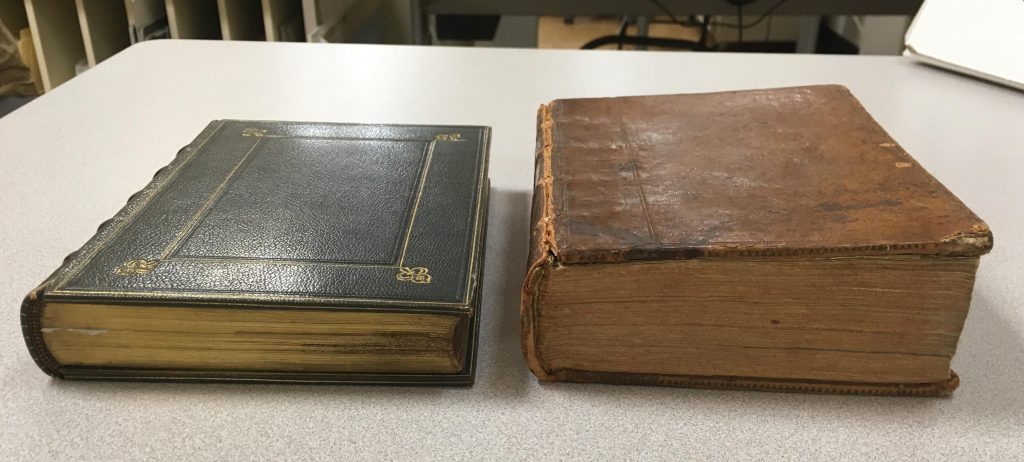

While these two books look very different, they are actually the exact same edition. They were both printed with the same setting of type and on the same paper. The book on the left is in a later binding than the one on the right, with some added edge gilding. But why the difference in textblock thickness? The one on the left was pressed very hard by the binder. It’s pretty incredible how compact a textblock can become with enough pressure -and pressing is not without its downsides. These books were letterpress printed and the dimensional impression of the type, which is an artifact of the printing process, has been completely pressed out of the thinner copy.

While these two books look very different, they are actually the exact same edition. They were both printed with the same setting of type and on the same paper. The book on the left is in a later binding than the one on the right, with some added edge gilding. But why the difference in textblock thickness? The one on the left was pressed very hard by the binder. It’s pretty incredible how compact a textblock can become with enough pressure -and pressing is not without its downsides. These books were letterpress printed and the dimensional impression of the type, which is an artifact of the printing process, has been completely pressed out of the thinner copy.

By Rachel Penniman, Conservation Specialist

What do you when your anatomical flap book has gone all to pieces? This book arrived with every flap piece detached from its page but all still in good condition. Having the flaps detached actually made it easier to see the usually hidden backs of those parts, but what is a flap book without a flap?

To maintain access to the individual parts but still retain the interactive and movable essence of the book, we decided not to reattach the loose parts to their pages. Instead they were put in Mylar pockets hinged to a Mylar backing sheet. So the flaps move in a way similar to what was originally intended while still allowing the back of each part to be more accessible.

Several items came down for boxing this week. These two items are from the Lisa Unger Baskin Collection. The top is a metal “Votes for Women” sign in a delightful bluebird design. Below are two sides of a small sampler pin cushion that is stitched on the finest linen ground I’ve seen.

These objects represent two aspects of women’s work. The work of the hand, that was/is often taught as a useful life skill. And the work of women as full citizens of their country…the work of standing up for your rights and exercising your right to vote. The Baskin Collection is full of objects like these and it is a real thrill and honor to have them come to the lab for custom enclosures.

As part of the Rubenstein Library Renovation Project a few years ago, the Special Collections Hallway Gallery was enlarged and rebranded as the Rubenstein Photography Gallery. The 67′ by 25′ space features a different collection from the Archive of Documentary Arts every few months. Because it still functions as a primary route through the building, the gallery provides an inviting environment for visitors to experience the library’s photographic collections.

We have been monitoring the environmental conditions within the space continually since it reopened in 2015. Although the temperature stays very stable in the building throughout the year, we do see some fluctuation in the relative humidity (RH) for the gallery. In the coldest winter months, public spaces tend to become very dry because of the heating systems. The question has been lingering in our minds: what are the environmental conditions that the artwork is experiencing inside the frame? Last fall, a small working group from Conservation, Exhibitions, Preservation, and the Archive of Documentary Arts gathered to design a simple experiment to try and answer this question.

As part of this experiment, we wanted to not only measure the temperature and RH within our normal frames, but see if there was something simple we could do to buffer any changes to those conditions. While there are many options available to change the conditions inside a frame, we determined the easiest (and cheapest) option would be to seal frame contents in a relatively impermeable package.

Framed photographs in our galleries include several components inside each frame. The glazing of our frames is a UV-filtering acrylic. Beneath that is a window mat cut to the size of the artwork. The print is mounted to another piece of mat board underneath. At the back of the package is a piece of corrugated board made of white plastic (polypropylene). We hypothesized that by taping the outside edges of this “package” of material with polypropylene tape that the air exchange inside the frame could be significantly reduced and therefore reduce the change in RH. We decided to set up two identical frames for comparison, one with a sealed package and one without.

We acquired two HOBO MX2300 Temp/RH dataloggers with external sensors and I set to work fitting them into two of our standard gallery frames.

The datalogger sensor is much thicker than the art that usually goes inside one of these frames, so I had to build up the thickness of the package with several layers of mat board. I created a central stack of mat board with a window cut to fit the sensor. I chose not to use full sheets of mat board for a couple of reasons:

The datalogger sensor is much thicker than the art that usually goes inside one of these frames, so I had to build up the thickness of the package with several layers of mat board. I created a central stack of mat board with a window cut to fit the sensor. I chose not to use full sheets of mat board for a couple of reasons:

An inkjet print with a cut mat and the glazing was placed on top of the sensor. The sensor cable was passed through a hole cut in the corrugated plastic, allowing me to mount the logger to the back of the frame. The contents were all stored in a stable 45% RH environment for several weeks before installation. With the package all together, I sealed up the outer edges as well as the hole in the plastic backing with clear tape. The sealed package was then placed inside the metal and wood frames.

We installed our sealed and unsealed experiment frames in the gallery in early December 2017, along with a new show. The frames were mounted on a small wall, next to the window to our reading room, so as to be less of a distraction from the rest of the exhibit and to be in close proximity to the data logger which monitors the gallery space.

The inkjet prints we included in each frame had a short description of the experiment so that curious patrons would understand the the purpose of their unusual positioning.

After five months, we took the frames down and compiled all the environmental data. In the graph below, the gallery conditions are marked in grey, the unsealed frame is marked in yellow, and the sealed frame is marked in blue. Temperature values are displayed on the left, while RH values are displayed on the right.

The data confirms that the space maintains temperature very well, staying right around 70 degrees Fahrenheit. The RH in the gallery space does bounce around quite a bit throughout the winter months, fluctuating between around 50% and 20%. Late January 2018 seems to have been particularly volatile.

We were very surprised at how well each frame responded to the conditions in the gallery. Even inside the unsealed frame, we see a significant smoothing out of the RH graph: the over 30 point spread of the gallery RH is reduced to around 12% change in the unsealed frame and the contents did not drop below 30% RH. The sealed frame package performed very well, with only about 6% overall RH change in 5 months.

While the methodology of this experiment does have flaws, it is an inexpensive and adaptable approach to measuring environmental conditions. We can be reassured that our normal framing practices protect prints from drastic changes, even in the most volatile months. We can also take the relatively simple and cost-effective step of sealing the frame package to provide additional protection for more sensitive materials. This experiment has raised questions of how other methods, such as sealing the frame package differently or adding pre-conditioned board, might compare. It is likely that our investigations will continue, so that we can make the best choices for our collections.

We have posted about hurricane awareness and disaster response before. With hurricane Florence on the southeast coast we wanted to round up information for those that may be affected by this storm.

For more information on state-wide emergency information:

North Carolina Department of Public Safety

South Carolina Emergency Management Division

Virginia Department of Emergency Management [site seems to be down at posting]

The National Heritage Responders (NHR) – formerly the American Institute for Conservation – Collections Emergency Response Team (AIC-CERT) – responds to the needs of cultural institutions during emergencies and disasters through coordinated efforts with first responders, state agencies, vendors and the public. Volunteers can provide advice and referrals by phone at 202.661.8068. Requests for onsite assistance will be forwarded by the volunteer to the NHR Coordinator and Emergency Programs Coordinator for response. Less urgent questions can also be answered by emailing info@conservation-us.org.

Cultural institutions in FEMA-designated disaster areas of Texas, Louisiana, Florida, and other impacted states and U.S. territories can apply immediately for NEH Chairman’s Emergency Grants of up to $30,000 to preserve documents, books, photographs, art works, historical objects, sculptures, and structures damaged by the hurricane and subsequent flooding. Applications for emergency grants are available here (Word Document).

If you are ready to start recovery you can use the Emergency Response and Salvage Wheel ro recover collections. The Wheel is also available in an app on both Android and Apple devices. Many other useful apps are out there to help you find information or organize a response.

Local and state organizations such as state archives, museums, university libraries, etc., will have experts on staff that can help answer collection emergency questions. Many states also have state-wide preservation groups with experts who can help (e.g. the North Carolina Preservation Consortium, LYRASIS, Texas Library Association). LRYASIS Performing Arts Readiness has experts to help performing arts organizations respond to disasters.

September is National Preparedness Month. Even if your institution was not affected by recent storms, now is a good time to review your current disaster plans and training. The Alliance for Response links cultural heritage and emergency response representatives. There may already be a local AFR network near you or you could consider forming one.

By Rachel Penniman, Conservation Specialist

In conservation there are so many different materials to learn about and each one has specific and unique properties that can impact how we approach a treatment. It’s impossible to know everything about every material. So any opportunity to cross-train or broaden a skillset can allow a conservator to better manage a wider range of objects.

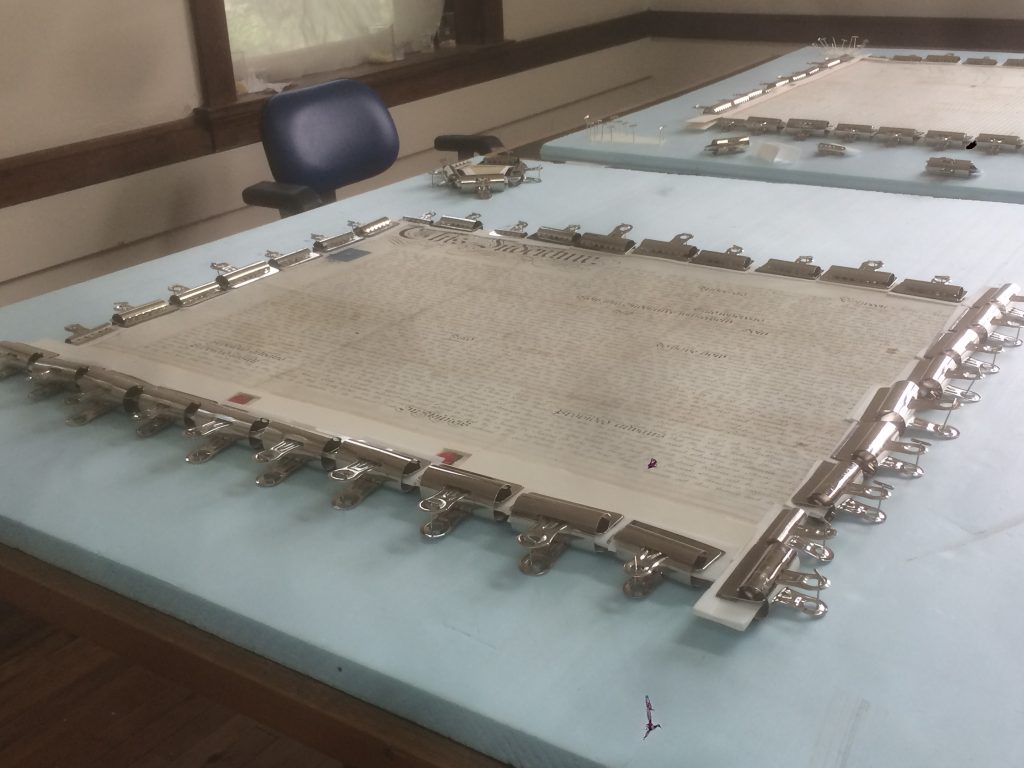

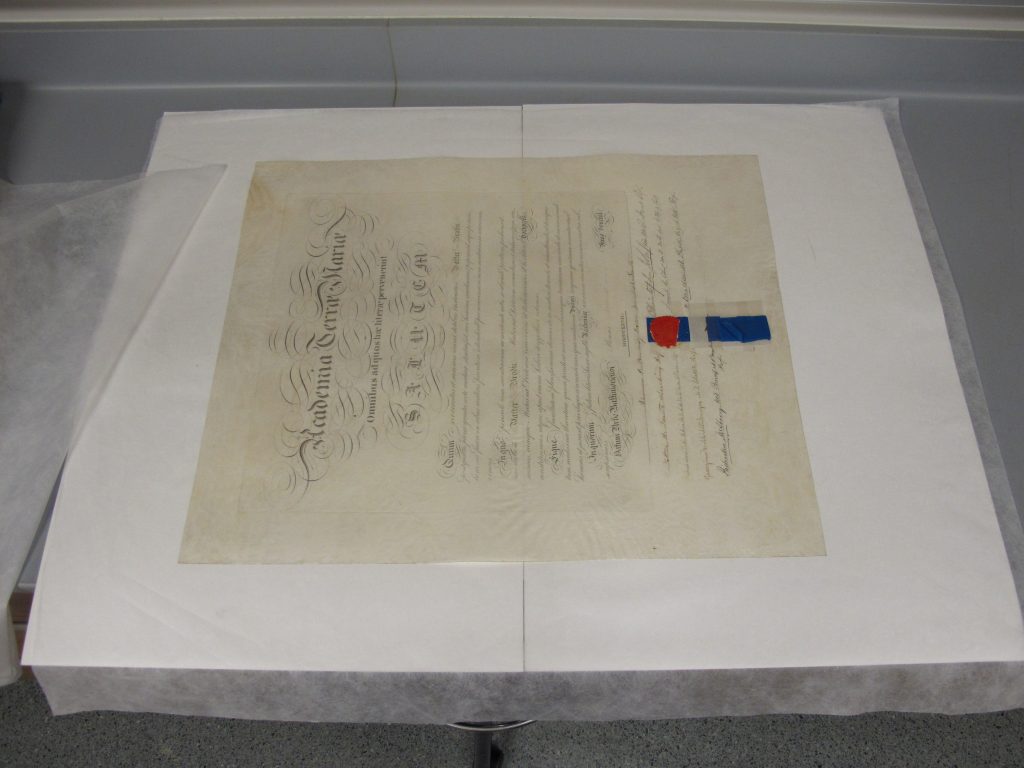

About a year ago I had the opportunity to attend Sheila Siegler’s Parchment Conservation workshop offered by the International Preservation Studies Center. It was a weeklong intensive on the history and preparation of parchment, parchment identification, and various treatment techniques.

We often get items made from parchment in our lab and I was especially interested in learning more about treatment methods for this finicky material. In the workshop I learned new methods for flattening and drying and came back to the lab eager to put those new skills to use.

Last week I had the opportunity to pass on some of those skills to North Carolina Museum of History Object Conservator Jennifer French. She had a parchment document in her collection in need of flattening and was looking for advice on how best to manage it. Our lab has previously collaborated with NC Museum of History when Textile Conservator Paige Myers visited our library to provide advice about a silk banner in our collection and we were happy to return the favor. I took a field trip over to Jenifer’s lab and we got to work.

The document was very cockled and uneven making it difficult to handle and house. Using a vapor chamber we created a high humidity environment to soften the parchment and ease out some of those wrinkles. While the parchment humidified we prepared our materials for drying. The humidification was a slow process so we had plenty of time to talk shop, sharing tips and tricks for an assortment of other treatments.

Once the parchment had been humidified for many hours the larger wrinkles were relaxed and it was much flatter already. We transferred the document to dry between felts and blotters under plenty of weight (those heavy conservation books come in handy).

A little over a week later Jennifer checked on the document and found it had flattened considerably. It still has some areas of minor undulation but it’s so much better, and more than good enough to be handled and rehoused.

For now the parchment will stay under weights until Jennifer and I meet up again to create an enclosure that will ensure the parchment stays safe and flat in the museum’s storage.

This kind of cross-institutional collaboration on projects was not only great fun but a rare opportunity for hands on information sharing and skill building. As conservators we get by with a little help from our friends.

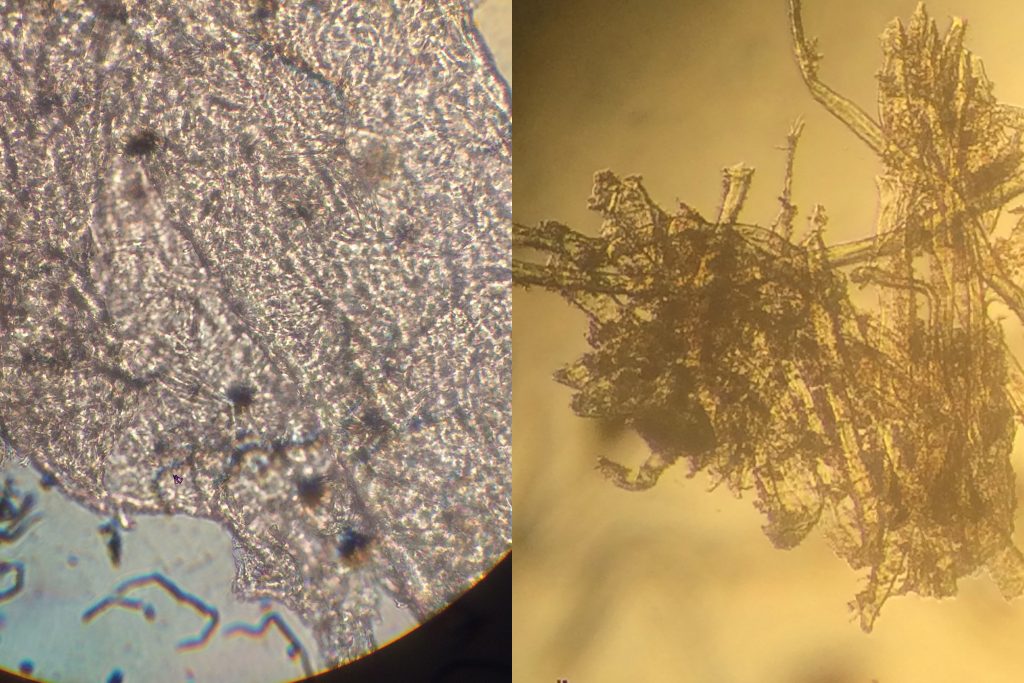

Late last week our lab hosted a 3-day workshop, taught by Jennifer McGlinchey Sexton, on Tools and Techniques for UV / Visible Fluorescence Documentation. Colleagues from libraries and museums around the country joined three DUL staff members to learn about the necessary equipment and to develop practical skills in capturing UV/visible images for use in conservation.

A great deal of the discussion centered around equipment. We looked at several kinds of UVA lamps that are currently on the market and talked about the filtering necessary on both lamps and cameras to reduce infrared and visible light. We also went over some methods for testing the quality of the lamp.

A great deal of the discussion centered around equipment. We looked at several kinds of UVA lamps that are currently on the market and talked about the filtering necessary on both lamps and cameras to reduce infrared and visible light. We also went over some methods for testing the quality of the lamp.

Capturing UV/visible images can be challenging and while standards have been widely adopted in recent years for conservation imaging under normal illumination, the same is not so true for UV documentation. Jennifer described several workflows for setting the white balance and selecting the best camera exposure settings using either home-made or standardized fluorescent color targets.

Capturing UV/visible images can be challenging and while standards have been widely adopted in recent years for conservation imaging under normal illumination, the same is not so true for UV documentation. Jennifer described several workflows for setting the white balance and selecting the best camera exposure settings using either home-made or standardized fluorescent color targets.

We had converted both our normal photo-doc space and the “dirty room” (our mold remediation and chemical storage space) into imaging work spaces, so the workshop participants were able to break up into two groups and practice. It was very useful to have two spaces and enough equipment that everyone could try the process several times and ask questions.

This workshop was a great opportunity to learn exactly how to add UV/visible to a conservation program’s documentation capabilities. It gave the participants a grounding in both the functionality of the equipment and a framework for consistently producing high quality images. For the Duke library staff who participated, this workshop also added some perspective to the work we have done in the last year or so with Multispectral Imaging.

We are so thankful to Jennifer McGlinchey Sexton for teaching, to Tess Bronwyn Hamilton for assisting, and to FAIC for sponsoring such a great experience!

Today is the last day for Phebe Pankey, our HBCU Library Alliance/University of Delaware Winterthur intern. The past two months have flown by. We have thrown a whole semester’s worth (maybe more) of information at Phebe in eight weeks. She has learned a lot of new skills and has applied those skills to projects in the lab.

Some of the skills she has learned include:

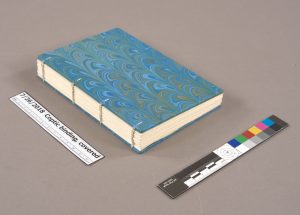

Henry taught Phebe how to sew a Coptic binding. Isn’t her first book beautiful? Phebe completed 494 repairs and custom enclosures during her internship. She completed work for the general collections including Perkins Library, Music Library, and Lilly Library. She also completed 119 repairs for Rubenstein Library in support of our digitization project to scan the collections in “Section A.”

A big shout out to Kelly Wooten, Research Services and Collection Development Librarian in the Sallie Bingham Center, for hosting a show and tell of artist books. These really made an impression on Phebe, who is an art major. It’s great to see someone get inspired by our collections and our people.

We also scheduled tours all over the library and across the greater Raleigh-Durham-Greensboro areas. Some of these were:

As we wrapped up this week we were lucky to have lunch with Miranda Clinton who is a student at NC Central University. She interned at the Library of Congress. We asked her to lunch to hear about her experience. Sounds like she had an amazing time there.

If you want to look back at some of the other work Phebe did, here are the blog posts:

HBCU Library Alliance Internship Announcement

Everyone in the lab helped Phebe learn new skills. Thanks to Erin Hammeke, Rachel Penniman, Mary Yordy, and Sara Neel for being so giving of your time and expertise. Thanks to everyone at Duke Libraries for being supportive of Phebe and generous with your time. Thank you to all the organizations that gave us tours. It’s always educational to see other labs and how they compare to ours. Thanks to the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation for awarding us a grant to help support this internship. And a big thank you to all the student interns who made the first year of this program successful. We can’t wait to see where you all go next.

It’s that time of year again when we report our annual statistics to our administration. We thought we would share these with you, too.

1,093 Book Repairs (down 38% from last year)

1,066 Pamphlets (down 38%)

1,392 Flat Paper (down 87%)

5,975 Protective Enclosures (down 15%)

66 Disaster recovery

8 Exhibit mounts (down 64%)

746 hours of time in support of exhibits (includes meetings, treatment, installation, etc.) (up 452%)

1,002 items repaired for digital projects (down 90%)

38% of total work was for Special Collections

62% of total work was for Circulating Collections

74% of work was Level 1 [less than 15 minutes to complete]

23% of work was Level 2 [15 minutes – 2 hours to complete]

3% of work was Level 3 [more than 2 hours to complete]

Looking at the three year trend you can see the impact of two things. First, we had a steep decline in paper repairs because last fiscal year we were working on a mass digitization preparation project (dark red line). Those numbers skewed our stats for FY2017. In February, Tedd Anderson resigned as our conservation technician, and Mary Yordy reduced her hours. You can see their impact on the stats. Tedd did the majority of custom enclosures (green line) for Rubenstein Library. And both Tedd and Mary repair general collections materials (light red line). We had a huge exhibit project this fiscal year that included a lot of complicated and time consuming repairs. You see a marked decrease in the percentage overall of items repaired for Rubenstein Library, but there was a marked increase in length of time we spent on those repairs. So the percentage is down, but the number of Level 3 repairs are up.

Not Everything Is A Statistic

We hope you enjoy looking back at the year that was FY2018 as much as we did. We can’t wait to see what FY2019 brings.