Muffins baked and blog post written by Jessica Janecki, Rare Materials Cataloger

When looking for a recipe to test, I immediately remembered a book I had cataloged for the Lisa Unger Baskin Collection , Ladies’ Indispensable Assistant, published in 1852 (available in digitized form through Hathi Trust or in print.

This book was memorable for its extraordinarily long title. When faced with titles of this length, catalogers frequently resort to truncation, but I had risen to the challenge:

Ladies’ indispensable assistant : being a companion for the sister, mother, and wife, containing more information for the price than any other work upon the subject : here are the very best directions for the behavior and etiquette of ladies and gentlemen, ladies’ toilette table, directions for managing canary birds : also, safe directions for the management of children, instructions for ladies under various circumstances : a great variety of valuable recipes, forming a complete system of family medicine, thus enabling each person to become his or her own physician : to which is added one of the best systems of cookery ever published : many of these recipes are entirely new and should be in the possession of every person in the land.

This mixing of food and medicine is fairly common in household management works of the time, when cooking, preparing home remedies, and caring for invalids all fell under the purview of the mistress of the household, but I had never before seen a household management book with instructions for keeping canaries, let alone one which felt the need to advertise this in the title.

In the hopes of producing something palatable and edible, I skipped the sections on home remedies and medicinal plants and went straight to the “valuable recipes.” I had high hopes, after all, the title page declared this “one of the best systems of cookery ever published.”

I settled on Muffins.

Reading over the recipe, I had all the ingredients. However, several steps were required to convert this into a usable recipe for modern kitchens. First, the recipe was short on instructions, lacking rising time, cooking time or oven temperature, information difficult to provide at a time when cooking might be done over an open fire or on a coal burning cast iron stove. Since this was essentially an enriched yeast dough, like a brioche with less butter, I consulted similar modern recipes to get an idea of cooking time and oven temperature. I decided on 400 degrees Fahrenheit and to simply bake until light brown as instructed.

On to the ingredients. A quart of flour is approximately 4 cups. By comparison, the muffin recipe in my trusty Better Homes and Gardens cookbook calls for 1 ¾ cups of flour to make 1 tin’s worth of muffins. So right away I knew I wanted to halve the recipe. This was also before modern instant yeast, so I knew the measurement of a half cup of yeast would be for some sort of home made yeast preparation, recipes for which I had leaved past before spotting the muffins. Since I did not want to grow my own yeast, I decided to use the active dry yeast I had on hand. 1 teaspoon would be the usual amount of yeast to use with my proposed amount of flour if I were making bread. The recipe called for “wheat flour,” which to modern readers might mean “whole wheat,” but in 1852 whole wheat flour was called graham flour, after health nut and fiber aficionado Sylvester Graham. Since this was a yeasted bread dough, I decided to use the white bread flour I had on hand. I also substituted cashew milk for regular milk, since that was what was in my refrigerator.

Here is the recipe I used, adjusted to modern measurements and reduced by half:

2 cups unbleached bread flour

1.5 cups cashew milk

1 teaspoon active dry yeast

1 tablespoon sugar

1 beaten egg (grade A large white)

½ teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon melted butter

To compensate for my modern yeast, I proofed it in the warmed cashew milk with a tablespoon of sugar before adding the yeast-milk mixture to the flour. This made a very wet and sticky dough. It was so wet that I did not bother with covering it and simply left it on top of the stove to rise.

I checked at 10 minute intervals until it looked “light,” hoping for a doubling in volume. After an hour I decided it had risen enough. I scooped the batter-like dough into a greased muffin tin and baked until light brown, which turned out to be 25 minutes.

These were delicious hot out of the oven. They were crispy on the outside and moist and tender on the inside, sort of a cross between a roll and a muffin. They also reheated well in the microwave. I would make these again.

The final product was incredibly tasty. The gumbo, which had three kinds of thickener (filé powder, roux, and okra slime), had a decadent, creamy texture. The tomato was not overwhelming and provided a tangy, sweet undercurrent that blended nicely with the kick of the red pepper flakes. I had to add a bit more salt to balance the flavors in the dish to my liking. Overall, it was a satisfying meal that showcased both beef and okra beautifully.

The final product was incredibly tasty. The gumbo, which had three kinds of thickener (filé powder, roux, and okra slime), had a decadent, creamy texture. The tomato was not overwhelming and provided a tangy, sweet undercurrent that blended nicely with the kick of the red pepper flakes. I had to add a bit more salt to balance the flavors in the dish to my liking. Overall, it was a satisfying meal that showcased both beef and okra beautifully.

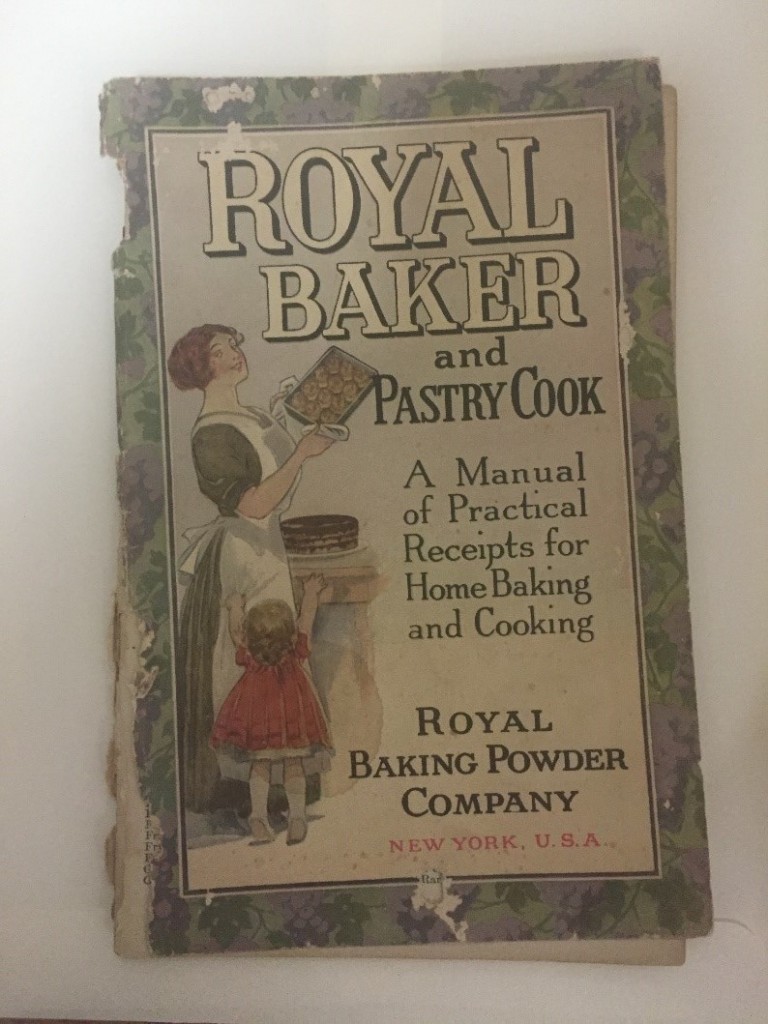

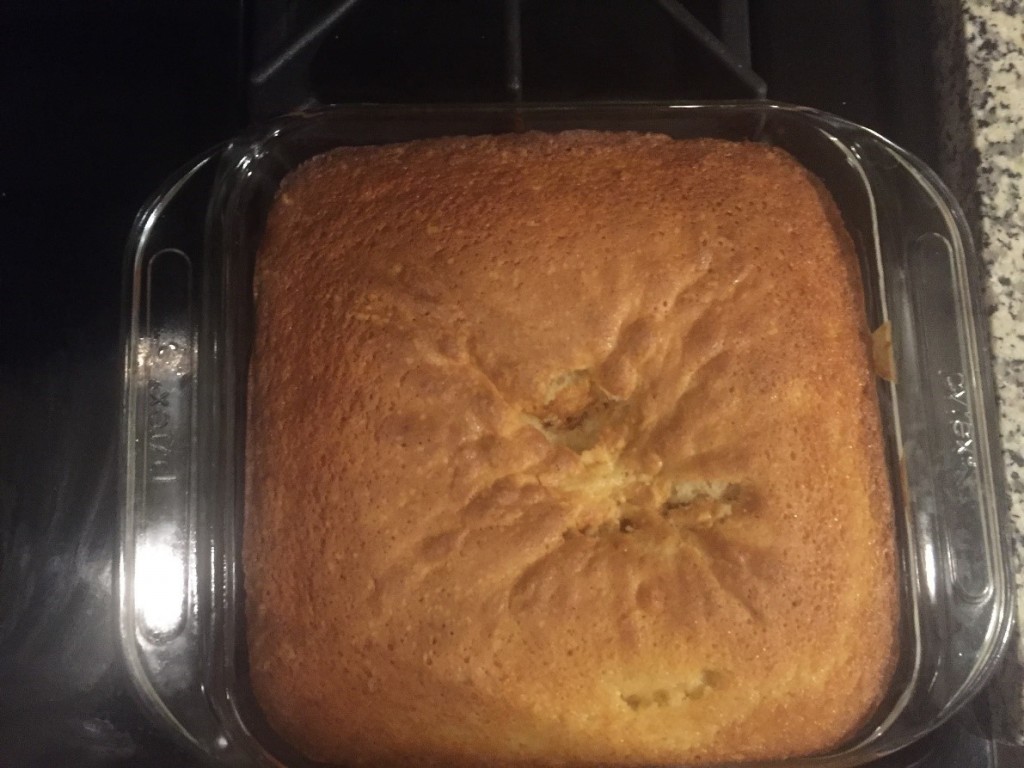

Financiers are most typically baked in individual molds. Royal Baking Powder specifies a fluted pan, which I don’t own. I thus didn’t follow the recommendations for either financiers or the almond cake and baked it in a clear pan. This was probably a mistake, as glass pans do not conduct heat as well as metal ones (Lawandi, J.).

Financiers are most typically baked in individual molds. Royal Baking Powder specifies a fluted pan, which I don’t own. I thus didn’t follow the recommendations for either financiers or the almond cake and baked it in a clear pan. This was probably a mistake, as glass pans do not conduct heat as well as metal ones (Lawandi, J.).

Two eggs well beaten, one-cup brown sugar, two teaspoons ginger, one-cup N.O. molasses (boiled), one-teaspoon baking soda, flour to roll out. Mix in the order given. I poured the molasses into a pot and watched small bubbles form and subsequently burst as the dark liquid began to heat. As the molasses boiled on the stove, I started mixing the ingredients in the order specified in the recipe. After the eggs had been beaten furiously with my new silver whisk, I began to measure the brown sugar for what I hoped would be a delicious dessert.

Two eggs well beaten, one-cup brown sugar, two teaspoons ginger, one-cup N.O. molasses (boiled), one-teaspoon baking soda, flour to roll out. Mix in the order given. I poured the molasses into a pot and watched small bubbles form and subsequently burst as the dark liquid began to heat. As the molasses boiled on the stove, I started mixing the ingredients in the order specified in the recipe. After the eggs had been beaten furiously with my new silver whisk, I began to measure the brown sugar for what I hoped would be a delicious dessert.

A manuscript (i.e. handwritten) cookbook can tell us a great deal about its creator. What foods were available to her? How would her family have celebrated holidays and birthdays? Was she an elite woman with a cook who could prepare elaborate dishes, or a farm wife who had to prepare simple, hearty fare and preserve her harvest to feed her family? Do the recipes reflect a particular ethnic or religious background or geographical location? As is the case today, routine meals do not require a recipe. It is the special occasion recipes, especially those that require careful measurements to work properly, that are recorded for future reference.

A manuscript (i.e. handwritten) cookbook can tell us a great deal about its creator. What foods were available to her? How would her family have celebrated holidays and birthdays? Was she an elite woman with a cook who could prepare elaborate dishes, or a farm wife who had to prepare simple, hearty fare and preserve her harvest to feed her family? Do the recipes reflect a particular ethnic or religious background or geographical location? As is the case today, routine meals do not require a recipe. It is the special occasion recipes, especially those that require careful measurements to work properly, that are recorded for future reference.