Post Contributed by John B. Gartrell, Director, John Hope Franklin Research Center

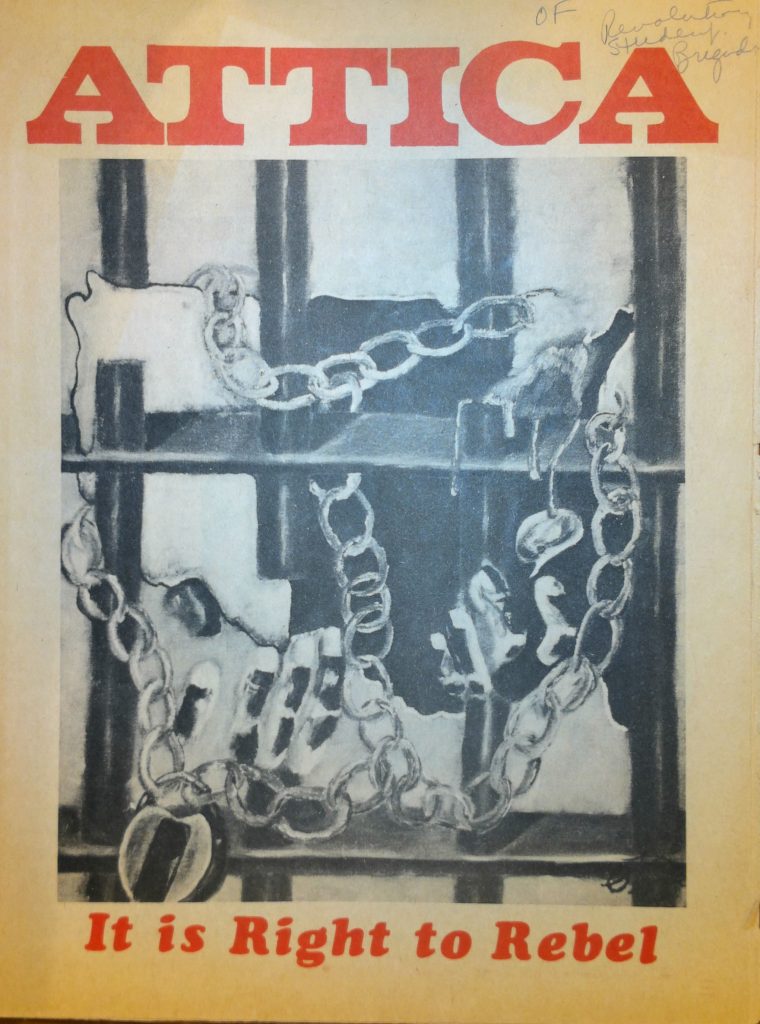

From May 31-June 1, 1921, the Tulsa Race Massacre took place in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, OK. Greenwood was one of the most economically prosperous African American communities in the country and earned the name “Black Wall Street.” The events of that day were said to have been sparked by the actions of a mob comprised of White Tulsa citizens that wanted to exact “justice” on a young black teen who had allegedly assaulted a White woman; which at the time was considered an affront to the Jim Crow power structure designed to keep African Americans in Tulsa, and throughout the country, in a subservient social class. The actions of that mob resulted in the looting and burning of businesses, churches, and homes, and the death of anywhere between 100 and 300 African American residents of Tulsa.

Among the victims during those tumultuous days was Buck Colbert Franklin, father of Dr. John Hope Franklin. Buck Franklin had relocated to Tulsa a few months prior to the massacre to grow his law practice. When the violence occurred, his offices, like so many other buildings in the Greenwood District, were burned and also delayed the arrival of his wife and children to join him in Tulsa for four years. As one the few practicing African American lawyers in the state of Oklahoma, Buck Franklin took up the lawsuits of the African American citizens as they attempted to seek insurance payments, civil and criminal settlements for the events that took place.

Some of the archival legacy of the Tulsa Race Massacre can be located in the collections of the Rubenstein Library and the John Hope Franklin Research Center. The following materials document what took place and the history of community members seeking justice, reparation, and reconciliation for two of the darkest days in our country’s history:

John Hope Franklin Papers – https://archives.lib.duke.edu/catalog/franklinjohnhope

- Writings Series, contains a number of writings by John Hope Franklin and others on the race riots

- Personal Series, Franklin family photographs including images of Buck Franklin

- Service Series, contains article clippings of news stories on the riots, also materials related to a 2003 Tulsa Race Riot lawsuit, Franklin’s participation in the Tulsa Race Riots Reconciliation Committee

- Audiovisual Series, VHS, The Greenwood Blues: The Tulsa Race War of 1921 (1983)

Thomas Dixon Jr Papers – https://archives.lib.duke.edu/catalog/dixonthomas

- Includes a letter from Jerome Dowd reflecting on the Tulsa Race Riot

Duke Oral History Program collection – https://archives.lib.duke.edu/catalog/duohp

- 13 interviews conducted in 1978 by Scott Ellworth for his study Death in the Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot, 1921

- Interviews with: B.E. Caruthers, Nathaniel Duckery, Robert Fairchild, Victor H. Hodge, Mozella Franklin Jones, Mr. and Mrs. I.S. Pittman, Henry Whitlow, N.C. Williams, Seymour Williams, William D. Williams

Events of the Tulsa Disaster by Mary E. Jones Parrish, 1922

Before they Die: survivors of the Tulsa Race Riot 1921, 2008

Magic City by Jewell Parker Rhodes, 1997 [fiction]

The Brown Papers were a series of publications written and produced by the National Institute for Women of Color (NIWC) as a platform to raise awareness and examine issues and concerns of women of color including lack of representation in politics, harmful and derogatory stereotypes, and systemic silencing of their experiences and voices. NIWC was founded as a non-profit institute in 1981 to create a national network for women of African, Alaska Native, American Indian, Asian, Hispanic, Latina, and Pacific Island heritage. NIWC started organizing annual conferences around the United States in 1982 and began publishing The Brown Papers in 1984 along with another periodical called Fact Sheets on Women of Color.

The Brown Papers were a series of publications written and produced by the National Institute for Women of Color (NIWC) as a platform to raise awareness and examine issues and concerns of women of color including lack of representation in politics, harmful and derogatory stereotypes, and systemic silencing of their experiences and voices. NIWC was founded as a non-profit institute in 1981 to create a national network for women of African, Alaska Native, American Indian, Asian, Hispanic, Latina, and Pacific Island heritage. NIWC started organizing annual conferences around the United States in 1982 and began publishing The Brown Papers in 1984 along with another periodical called Fact Sheets on Women of Color.