Post Contributed by Patrick Stawski, Archivist, Human Rights Archives

Reagan’s Gun-Toting Nuns: The Catholic Conflict over Cold War Human Rights Policy in Central America wins 2020 Juan E. Méndez Book Award for Human Rights in Latin America

Theresa Keeley’s important and wonderfully detailed book, Reagan’s Gun-Toting Nuns: The Catholic Conflict over Cold War Human Rights Policy in Central America (Cornell University Press, 2020), is the winner of the 2020 Juan E. Méndez Book Award for Human Rights in Latin America.

Theresa Keeley’s important and wonderfully detailed book, Reagan’s Gun-Toting Nuns: The Catholic Conflict over Cold War Human Rights Policy in Central America (Cornell University Press, 2020), is the winner of the 2020 Juan E. Méndez Book Award for Human Rights in Latin America.

This is the twelfth year of this prestigious award. The award is supported by the Duke Human Rights Center@the Franklin Humanities Institute, Duke’s Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, and the Human Rights Archives at the Rubenstein Rare Books and Manuscripts Library.

Reagan’s Gun-Toting Nuns is a deep dive into a formative period in human rights, Central American history, and the role of the faith community, in particular the Maryknoll order, on US policy. Keeley will accept the award via a Zoom event that is open to the public. The event will take place on March 16 from 5:30-7 pm.

The judges were unanimous in their praise. Prof. James Chappel, Hunt Assistant Professor of History at Duke University, noted that the book “tells a great story that most people, myself included, know little about. Catholicism, like human rights, is both global and local, and it takes a special kind of historian to explore it with humanity, moral passion, and archival rigor. By integrating geopolitics, theology, and gender into one beautiful narrative, Keeley does all of us a great service.”

Maria McFarland Sánchez-Moreno, currently a senior legal adviser to Human Rights Watch and a former Méndez award winner, commented that the book “covers a history about which I’ve long been curious and that has been central to US human rights policy toward Central America. It does so comprehensively, seriously, and with great care. The author did an impressive amount of research.”

Robin Kirk, chair of the judging committee and the co-director of the Duke Human Rights Center@the Franklin Humanities Institute, commented, “I learned so much from this book: about Central America, US policy, the Maryknolls, and continuing repercussions of divides within Christianity and their links to human rights. Even as an advocate in Latin America, I was unfamiliar with much of this history. So much of this framed the early development of human rights as US policy and a generation of American and European rights activists.”

When notified of the award, Keeley stated, “I am humbled to have my work recognized. At times, I struggled to find ways to convey Central Americans’ and missionaries’ experiences during the 1970s and 1980s. But it was nothing compared to what the people who lived through these difficult, and often violent, times endured. I am thankful to all of the human rights advocates, in the United States and Central America and especially the women religious, who trusted me with their stories. I hope the Méndez Award will bring recognition to them and to the greater need for the U.S. government to consider how its foreign policies affect the human rights of others.”

The judges would also like to extend congratulations to Dan Werb and his excellent City of Omens: A search for the missing women of the borderlands (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019), our runner-up. The judges praised the book’s epidemiological approach and the richly detailed research paired with the stories of the women Werb worked with on the US-Mexico border. Werb’s text was “very compelling and human,” wrote one, “and I loved that it shed light on worlds that most readers do not know about or care to know.”

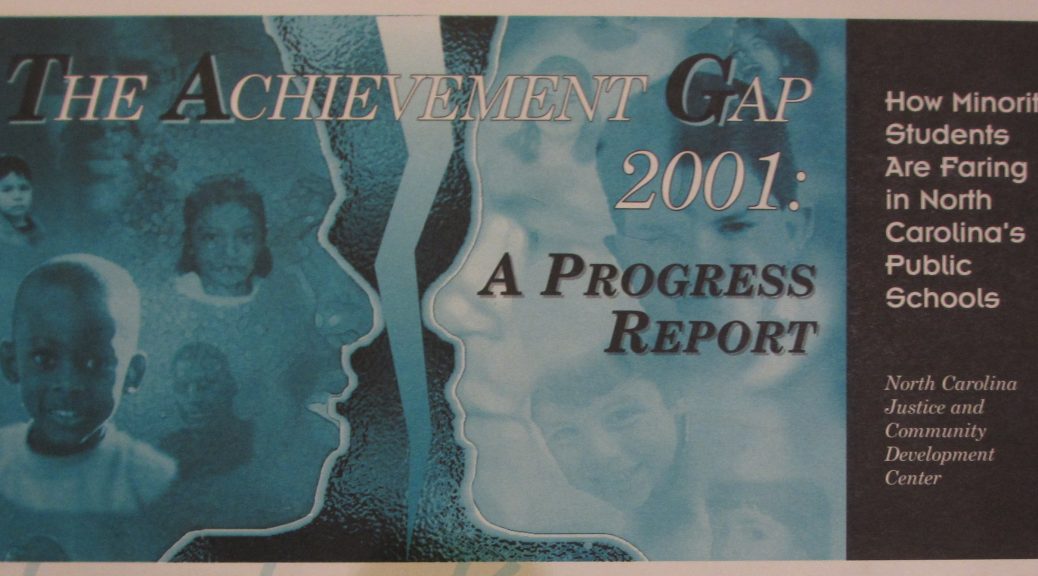

First awarded in 2008, the Méndez Human Rights Book Award honors the best current non-fiction book published in English on human rights, democracy, and social justice in contemporary Latin America. The books are evaluated by a panel of expert judges drawn from academia, journalism, human rights, and public policy circles.

For more information on the award and previous winners, see https://humanrights.fhi.duke.edu/programs/wola-duke-human-rights-award/.