There’s something satisfying about reading a journal, and I don’t think it has much to do with the fact that a lot of journals try to discourage readers from exploring their contents, either. Instead, what I think appeals to me about journals is the familiar and candid tone of an author writing to him or herself. It’s thrilling to feel like the secret confidante of someone whom you’ve never met. There’s a lot of honesty in a journal, and that honesty transcends time to resonate with people totally outside of the context of the author’s life.

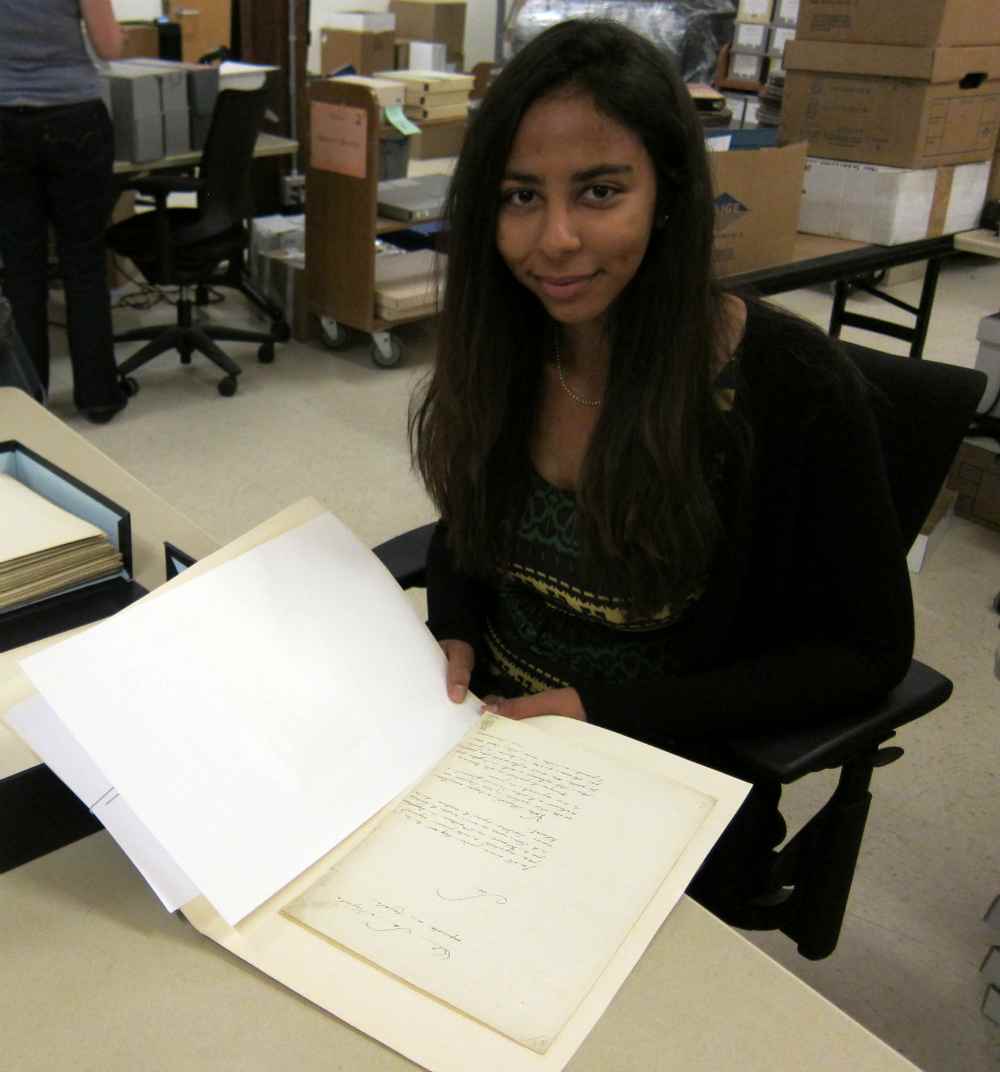

I’ve been privileged to work with the History of Medicine Collection in the Rubenstein Library this semester, and in the course of my project came across the journals of a young American medical student living in Paris, France in the early 1840s. Before I had really been able to familiarize myself with the contents of the journals – barriers mainly being Spencer’s handwriting – I imagined that the writing would be fraught with tales of the revolutions and political upheaval that characterized French politics in the 19th Century. What I found instead, though, was a window into the daily life of a bright, detail-oriented young medical student living in beautiful and romantic Paris, France even before the iconic Eiffel Tower was built.

The first entry in the journal is almost 30 pages long and describes a tour of Parisian monuments. Spencer starts with a jaunt around the grounds of the Palais des Tuileries and ends with a visit to the Arche de Triomphe on the Champs Elysées. When I said detail oriented, I was referring to things like the fact that Spencer recorded in yards the length and breadth of the Palais des Tuileries and described the arrangement and structure of the gardens there, too. The level of attention to detail, while surprising for a modern reader like yours truly, is likely because outside of recording the dimensions himself, Spencer would not easily be able to either recall or discover that information elsewhere. Another thing to remember is that photography hadn’t been really popularized yet, though it existed. 1840 is approximately contemporary with the birth of the Daguerrotype, an early photographic process. In 1840, if you wanted to remember something, you had to take down the facts yourself.

Even though it’s hard to imagine a Paris without the Eiffel Tower, some things in Spencer’s journals make him really accessible. For example, I was happy to find that he had an appreciation for puns; Spencer hearteningly described a fête happening down by the river as the “Seine of the action.” I totally LOL’d in the reading room at Perkins for that one, but then I do love a good pun.

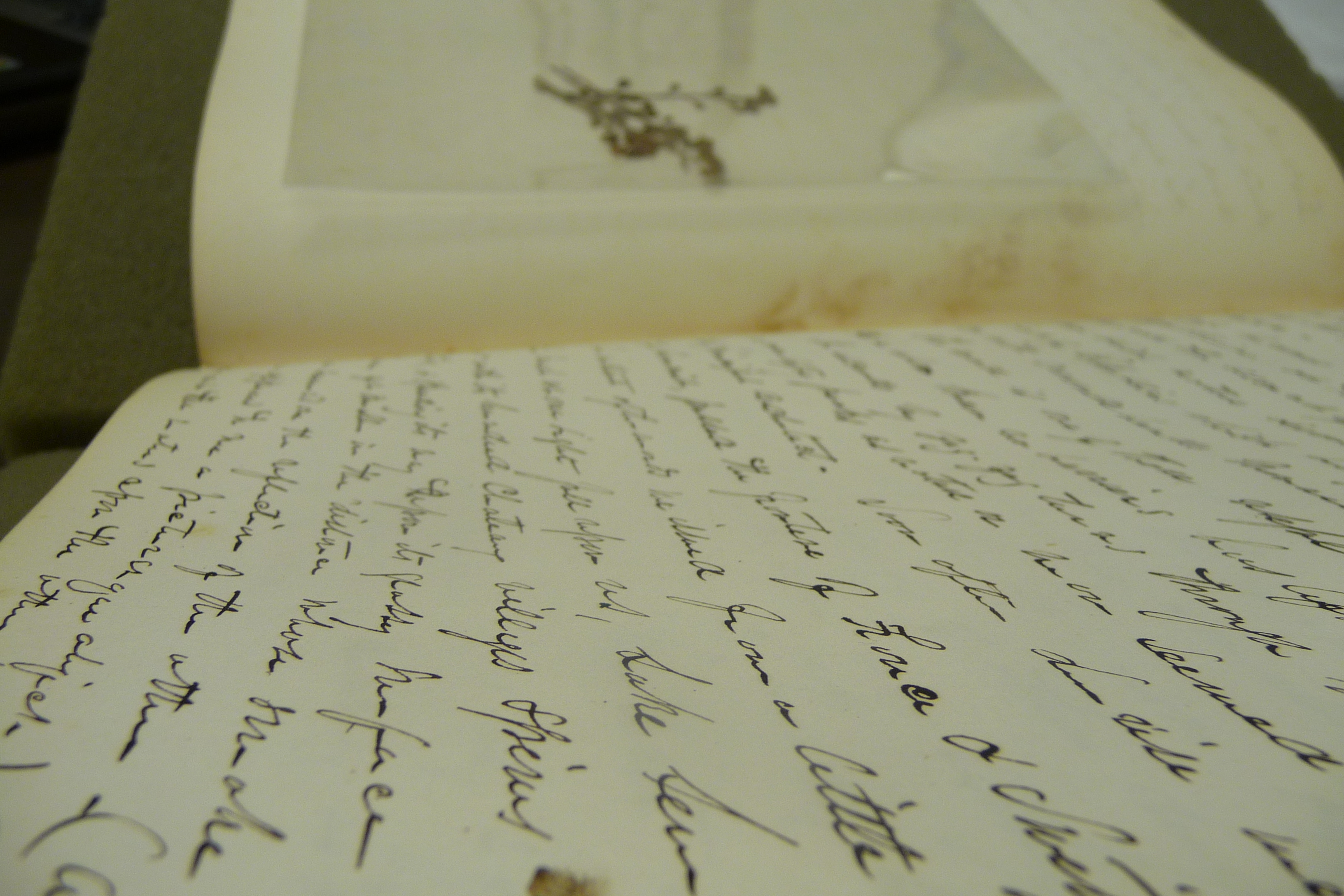

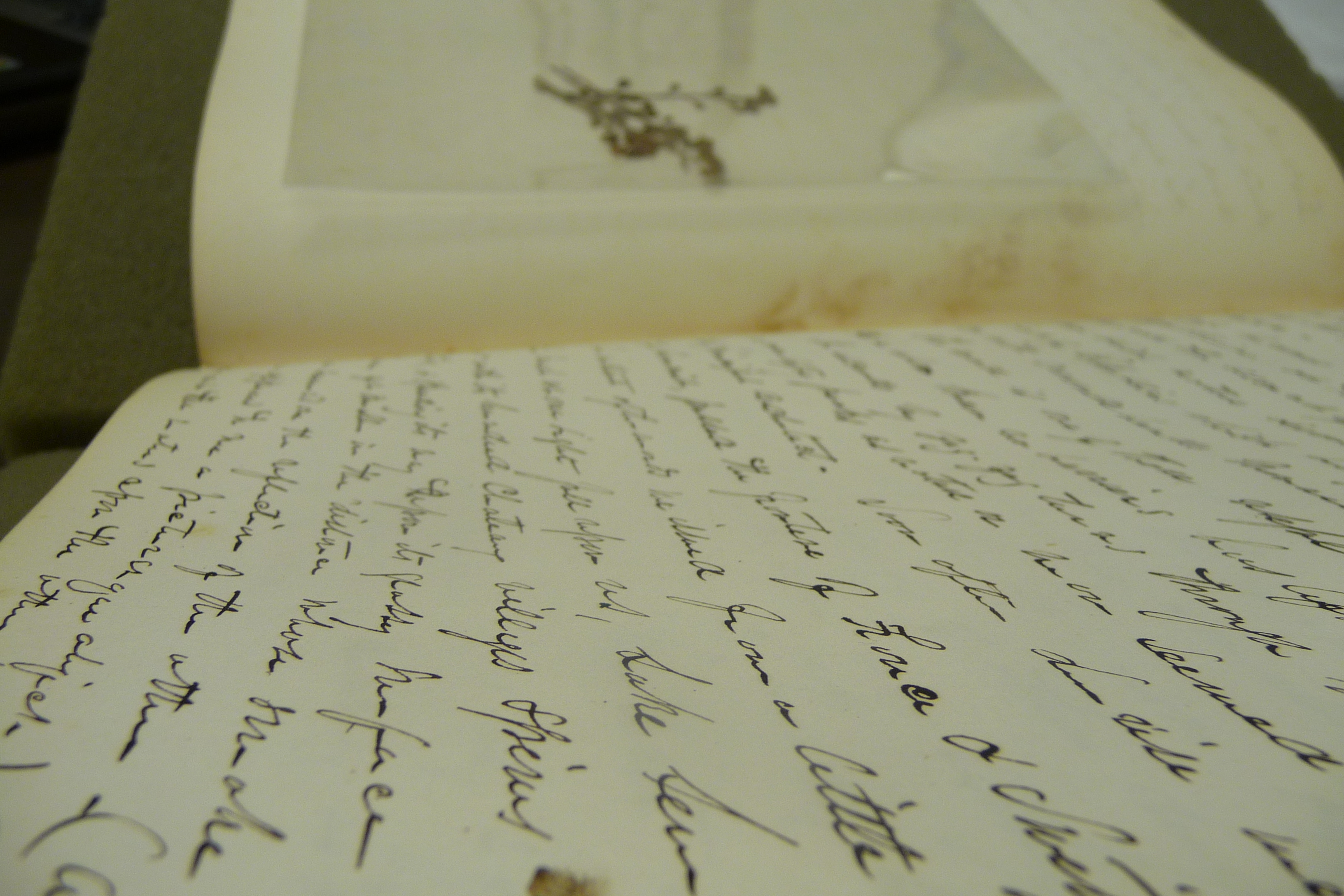

The tidbits that make Spencer seems so contemporary exist right alongside descriptions of things that make his experiences totally foreign. He writes about doing rounds with a physician and watching amputations. As you might imagine, the practice of surgery has changed rather a lot since 1840. From Spencer’s descriptions, amputation was a considerable part of a surgeon’s practice at that time. Spencer also describes a side-show that he saw in Paris in terms of the various medical ailments that were afflicting the performers. Spencer recorded his ideas about what was wrong with the four-legged man and the level of approximate curvature of the spine of a man with dwarfism. I thought it was fascinating to see these people through the lens of his medical training. The journals also hold some botanical specimens that Spencer collected during his time in France. One of them makes an appearance in the image posted here.

The History of Medicine Collection has another later manuscript by Thomas Spencer, too. We learn from it that upon his return to the United States, he took up practice as a pathologist in Philadelphia, PA. The records from Spencer’s practice are taken with the same careful attention to detail and in the same beautiful script as his journals.

The journals tell what Spencer saw. They are his carefully collected memories from the two years he spent based in Paris. His experiences, which are so different from our own, lay out the scope of history, but his personality, humor, and opinions make him seem like a peer.

Nathalie Baudrand was the History of Medicine Collections Intern for Spring 2012 and is a graduate student at UNC’s School of Information and Library Science.