Post contributed by Krystelle Rocourt (Trinity ’17), student assistant for the Radio Haiti Archive project.

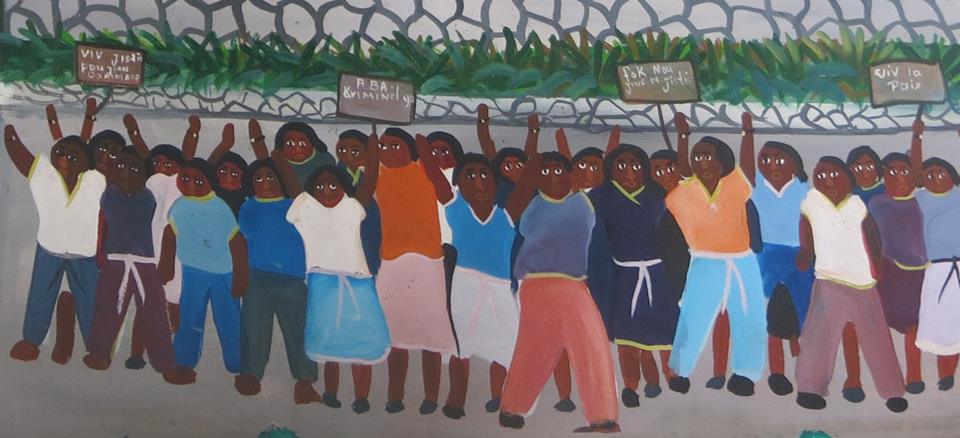

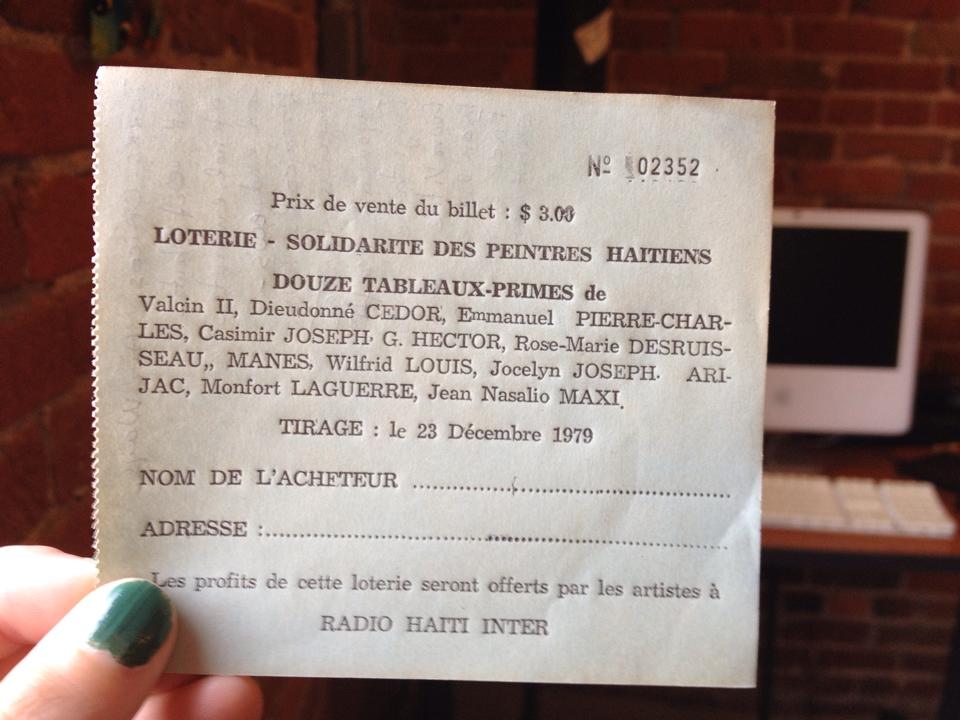

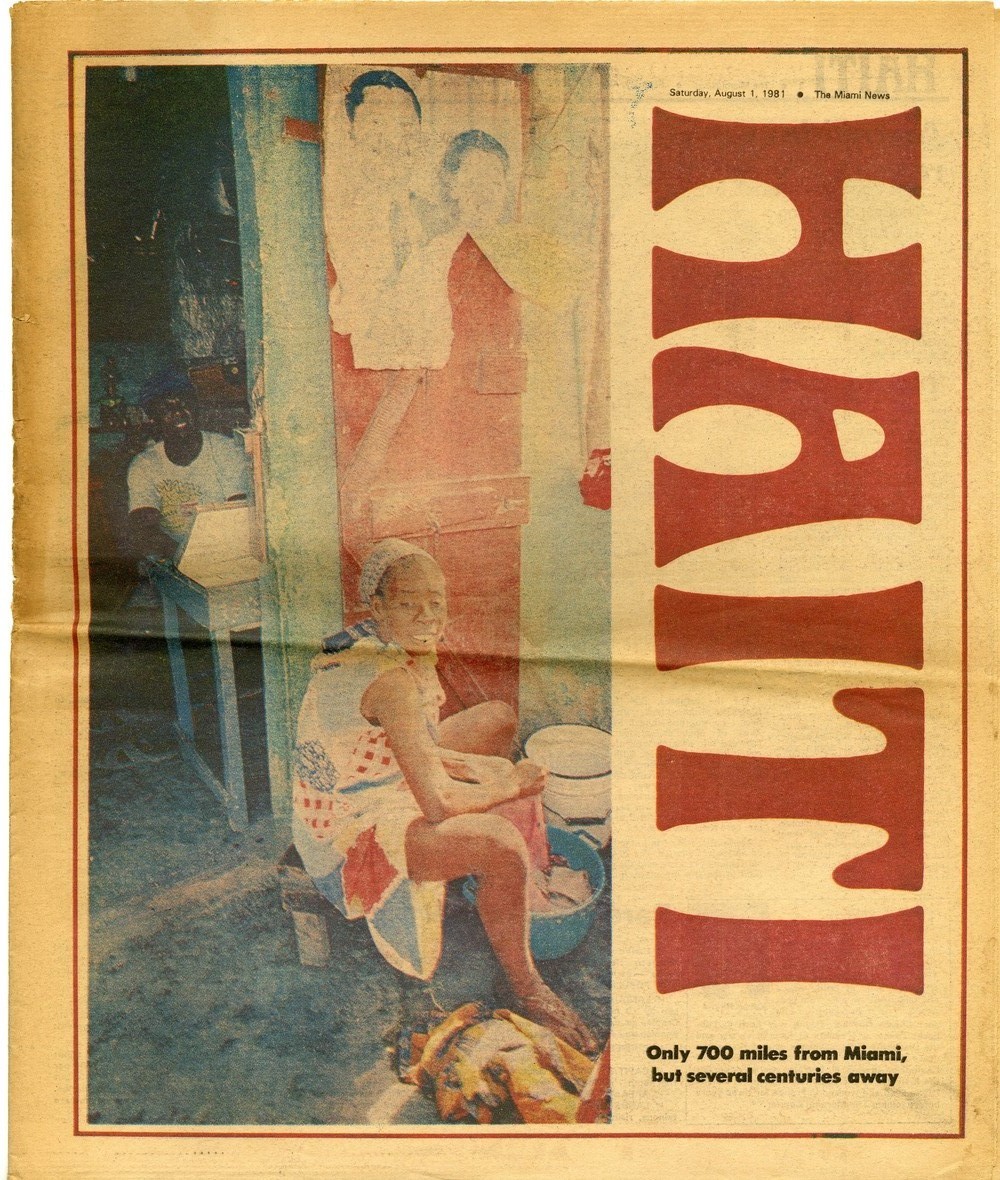

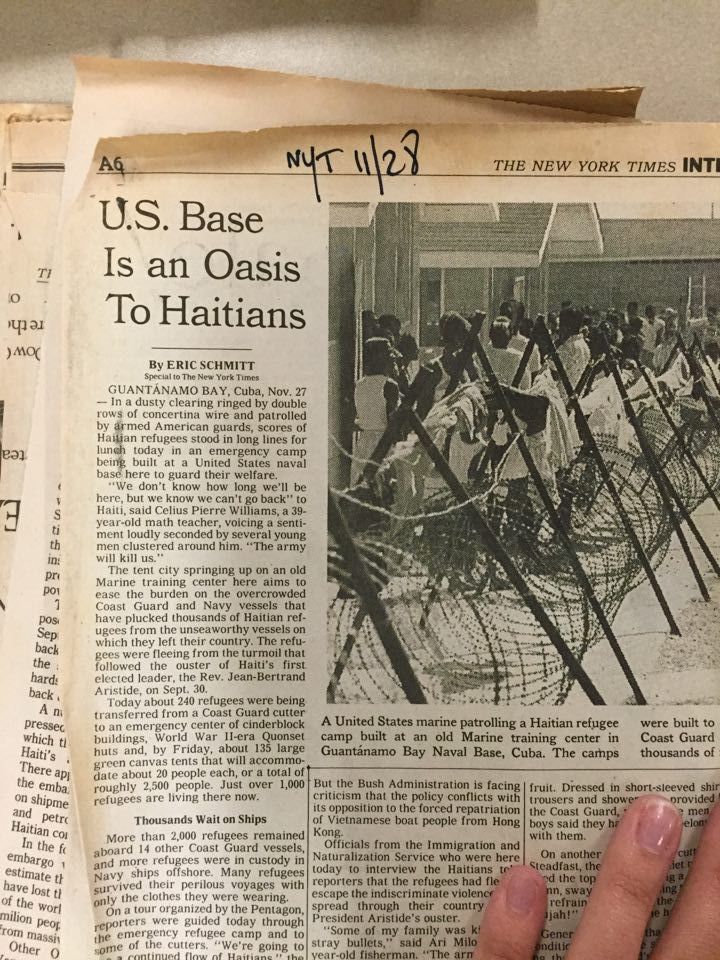

The international media has long presented a distorted image of Haiti, one that leaves out the multiplicity of our people, exoticizes our culture, and depicts poverty as universal, without context or history. Haiti is labeled the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere, a country teeming with chaos and suffering, the eternal recipient of foreign aid.

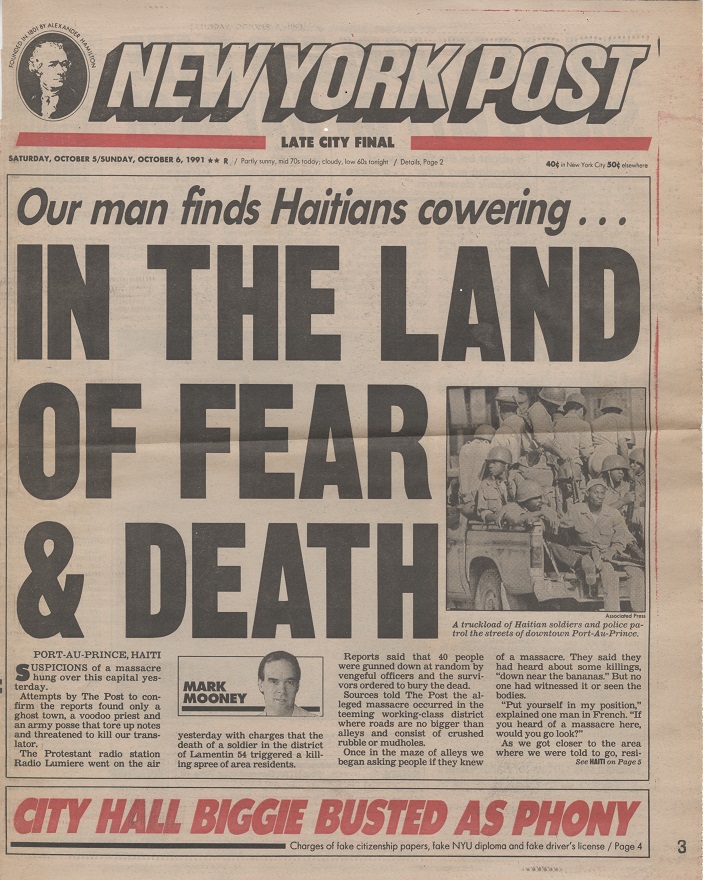

One of my tasks at the Radio Haiti archives is to help process the hefty stacks of US newspapers collected by Jean Dominique and Michèle Montas during their 1980-1986 and 1991-1994 exiles in New York. Often, I had to keep myself from being distracted by sensationalist headlines in order to get through the newspaper clippings that had yet to be sorted. Every so often, however, I would come across something so startling that I would have to pause to absorb the shock. How could such things be published in supposedly unbiased sources of international news? It disturbed me that people with limited knowledge could make derogatory claims that would have permanent effects on people’s understanding of Haiti’s place in the world.

When I came to Duke as a freshman, I had preconceived ideas of the struggles I would face, but a challenge to my identity as a Haitian was not one of them. Whenever I would tell people I was from Haiti, I would get skeptical gazes or looks of astonishment followed by remarks like “Haiti! Where in Haiti? Both your parents are from Haiti? Are they doctors working in Haiti?”, so that I could further validate the incongruence between my appearance and my claim. When I noticed a trend in these reactions, I began to reflect and question my origin and actually felt shaken when a simple “Yes, I’m Haitian” was not enough. I was not oblivious to the fact that I did not look like the “average Haitian”; I grew up very aware of this fact. It did not come as a surprise that I would be met with these reactions upon introducing myself, but as I thought about it, I began to uncover truths about my position in Haitian society that were difficult for me to accept. It was extremely uncomfortable to face the fact that I did not belong to the Haitian majority, but to a very small elite minority, because it confirmed the existence of the chasm between the two groups that I had observed my whole life but never fully come to terms with.

Never before had this difference invalidated my sense of belonging. My insecurity persisted, however, because it stemmed from the possibility that my sense of belonging was laced with ignorance. Could I truly claim to be part of a group whose struggle I never had to fully share? There is an undeniable and deep-seated social-class hierarchy in Haiti that often corresponds with the pigmentation of one’s skin. After Haiti won its independence, the first republic to emerge from a large-scale rebellion by enslaved people, conflict arose between Black Haitians and Haitians of mixed race, a division that remains to this day. Since Haiti’s birth as a free nation, its image has been vastly shaped by the outside world’s interpretations; the international media rarely depicts Haitians looking like me. Yet to claim skin color alone as the defining factor of Haitian identity would undermine my lived experience: if I am not Haitian, what am I?

Each time I left Duke and returned to the bubble of elite Port-au-Prince, the social system there seemed more and more problematic, one in which the rich and poor live side by side but are worlds apart. There were people who blatantly proclaimed that the divide between rich and poor was inevitable and necessary, and those who claimed that we were all “one nation” despite the inequality. No matter how idealistic and deceptively unifying it sounded to claim that all of us are one despite our social class and backgrounds, I felt it unfair to ignore the differences in our experiences as Haitians. Overlooking the divide leads to a form of hypocritical erasure, one that disregards the oppressive elitist perception projected onto one group by another. Denying the complex situation of social class in Haiti belittles the suffering of many and excuses the powerful for their contribution to this disparity. Though I’d often heard criticism of the “savior complex” of foreign aid workers in Haiti, I found it within our walls in air of superiority held by those overlooking the masses, who believed that the poor were the reason for the deprived state of the country today.

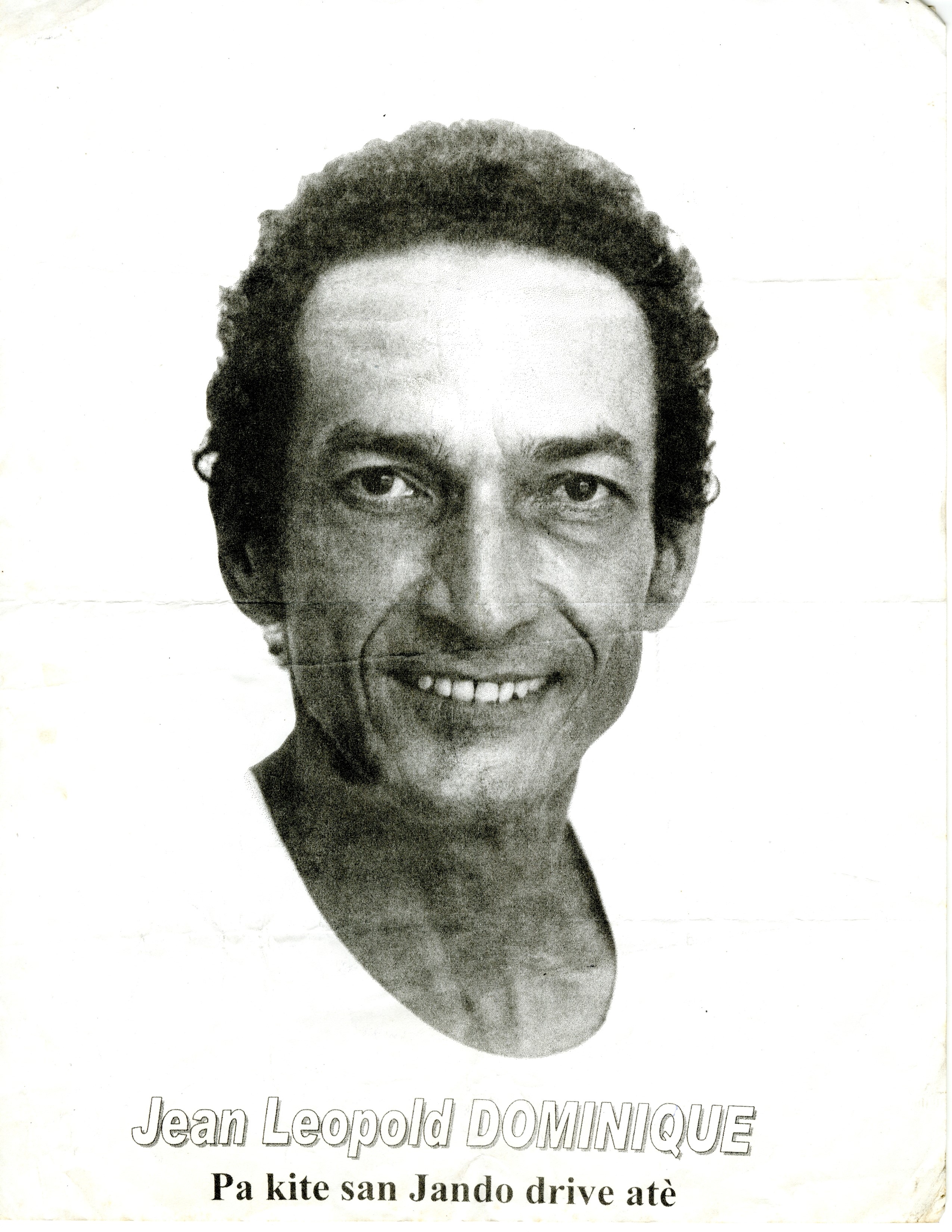

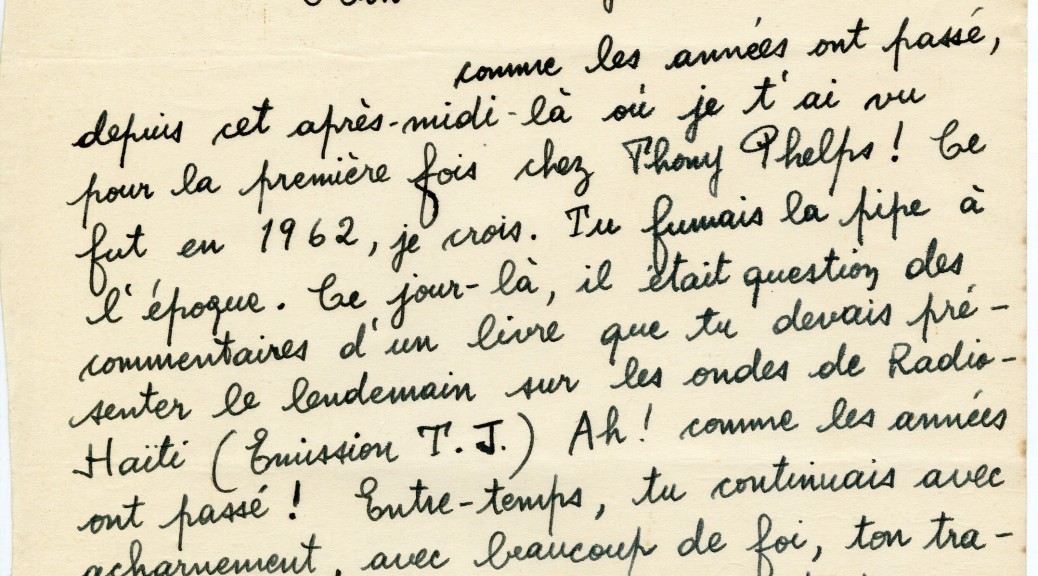

After my second summer at home, I returned to Duke as a junior and began to work as an assistant on the Radio Haiti project. In order to better understand the station’s work and legacy, I watched The Agronomist, the documentary about Jean Dominique and Radio Haiti. I had to pause the movie several times to collect my racing thoughts and feelings. I felt deep pain and nostalgia: what the film showed was at once so familiar and so foreign. I was angry that I had never heard many of these stories, that I had grown up among those same landmarks and never understood the events that had unfolded there not long before.

A veil lifted for me when I learned about the work of Radio Haiti, impacting how I thought about home. I heard uncompromised truth verbalized, one I had struggled to define and speak out myself. I discovered a way of thinking that seemed fair and just. I felt disappointed about the state of oblivion I had lived in for so long, as I was learning about events that my parents and grandparents had lived through, yet never spoken about within our household. The silence felt like an injustice to the lives taken and the history that left the nation the way it is today. Radio Haiti brought the truth to light and never compromised their mission to uphold this truth, even in the face of violence and intimidation. It brought me solace, and gave me the strength to challenge the perceptions that had been passed on to me and quieted the anxiety that told me that there was no place for those who contradicted and challenged the system. To see members of the mixed-race elite who choose to align themselves with the struggles of the urban and rural poor gave me courage to follow their steps. It instilled in me a desire and sense of responsibility to actively connect with the history of my homeland if I am to bear the title of being Haitian.

The Voices of Change project was made possible through a generous grant from the National Endowment of the Humanities.