Post contributed by Ashley Rose Young, a Ph.D. candidate in History at Duke University and the Business History Graduate Intern at the Hartman Center.

Throwing a Mardi Gras-themed party this weekend? Then check out this gumbo recipe!

New Orleans Carnival season is in full swing with Mardi Gras fast approaching. My Twitter feed is full of images of brightly clad parade goers and heaps of dazzling beads. Scrolling through my feed the other day, nostalgia overwhelmed me. I had been missing New Orleans, the subject of my dissertation research. In that moment, I wanted one thing: gumbo.

With a goal to kick off the Rubenstein Test Kitchen in 2017, I thought I could make gumbo from a historic recipe, satiating my emotional need for it while also sharing my passion for the dish with wider audiences. There was one flaw in my plan, though. I had already written a blog post for the Devil’s Tale on Shrimp Gumbo Filé. As I pointed out in that post, however, New Orleans-style gumbo is anything but formulaic and reflects the complexity of New Orleans’ Creole food culture. There were an infinite number of combinations that I could draw upon to make a gumbo dish that would look nothing like the one I had made a few years ago.

So, I set out to look for a gumbo recipe that stood in contrast to the meaty seafood stew I had previously made from the Picayune’s Creole Cook Book (1916). Whereas I tend to gravitate towards roux-based stews with chicken, ham, and seafood, I knew that there were entirely different gumbo traditions—ones that drew upon ingredients that I have never tried in my gumbos.

I found just the recipe I was looking for in an article published in a 1957 issue of Ladies Home Journal. This was a beef-based stew with tomatoes and okra, among other unfamiliar gumbo ingredients like basil and oregano. The recipe came from an article titled, “Main Dishes with a Southern Accent,” written by Dorothy James, a native New Orleanian.

Okra Gumbo

Buy 2 pounds of either stewing beef or veal cut into 1” cubes. Put in a heavy kettle or Dutch oven along with 2 cups water, 2 cups chopped onion, ¾ cup chopped green pepper, ¾ cup chopped celery, 2 cloves garlic, crushed. Season with 1½ teaspoons salt, 1½ teaspoons gumbo filé, 1 teaspoon sugar, ½ teaspoon basil, ½ teaspoon orégano, 1/8 teaspoon pepper and a dash of crushed red-pepper flakes. Gumbo filé is innate to gumbo as far as Southern cooks are concerned, but it is not generally available in the North. It may be omitted, in which case add a little more red pepper and herbs. Simmer, covered, for 1 hour. Separate the meat from the broth and set both aside. Make a brown roux with ¼ cup flour and ¼ cup bacon drippings. Add the broth, 4 fresh tomatoes, peeled and quartered, and 1 cup tomato sauce. Cover and cook until the sauce is well blended. Then add the meat, cover again, and simmer gently about 45 minutes longer. Stir occasionally to prevent sticking. Wash and trim 1½ pounds fresh okra. Then cut into ½” pieces—there will be about 3 cups. (You can use two 10-ounce packages of frozen okra). Add to the gumbo and cook another 20-30 minutes, or until the okra is tender. Serve with rice. Makes 6 servings.

The final product was incredibly tasty. The gumbo, which had three kinds of thickener (filé powder, roux, and okra slime), had a decadent, creamy texture. The tomato was not overwhelming and provided a tangy, sweet undercurrent that blended nicely with the kick of the red pepper flakes. I had to add a bit more salt to balance the flavors in the dish to my liking. Overall, it was a satisfying meal that showcased both beef and okra beautifully.

The final product was incredibly tasty. The gumbo, which had three kinds of thickener (filé powder, roux, and okra slime), had a decadent, creamy texture. The tomato was not overwhelming and provided a tangy, sweet undercurrent that blended nicely with the kick of the red pepper flakes. I had to add a bit more salt to balance the flavors in the dish to my liking. Overall, it was a satisfying meal that showcased both beef and okra beautifully.

As is the case with any recipe, there are tips, tricks, and “trade secrets” that are regularly left out. I’ve added some notes to help create the most flavor-packed gumbo possible.

I purchased a fatty beef brisket from the local grocery store. The more fat in the meat, the more flavorful the stock. I also patted my beef try with a paper towel (thanks for the tip, Julia Child) and browned it in 2 tablespoons of oil to start a nice faun on the bottom of the pan. After a few minutes, I pulled the beef out, added a bit more oil to the pan, and sautéed my vegetables for 5 minutes. Then, I added the beef back in along with the water and spices. I added an extra cup of water so that the beef was almost completely covered.

After letting the stew simmer for an hour, I separated the beef and broth, trimming the extra fat off the beef once the meat had cooled. In the meantime, I washed out my cast iron pot and prepped to make a roux, the base of most Creole stews. For a detailed lesson on how to make a roux, see my previous blog post on gumbo. This time, I decided to make a quick roux, in ten minutes or less. I heated up equal parts oil and fat over medium-high heat and stirred constantly. My roux went from butter yellow to Hershey’s chocolate bar brown in about 9 minutes. I poured the broth back in and then added the tomatoes and tomato sauce, and eventually the beef (watch for splatter from the hot roux).

After letting the stew simmer for an hour, I separated the beef and broth, trimming the extra fat off the beef once the meat had cooled. In the meantime, I washed out my cast iron pot and prepped to make a roux, the base of most Creole stews. For a detailed lesson on how to make a roux, see my previous blog post on gumbo. This time, I decided to make a quick roux, in ten minutes or less. I heated up equal parts oil and fat over medium-high heat and stirred constantly. My roux went from butter yellow to Hershey’s chocolate bar brown in about 9 minutes. I poured the broth back in and then added the tomatoes and tomato sauce, and eventually the beef (watch for splatter from the hot roux).

Finally, I added in the okra, and allowed the gumbo to simmer for another 30 minutes, while I prepared rice.

Voila!

Financiers are most typically baked in individual molds. Royal Baking Powder specifies a fluted pan, which I don’t own. I thus didn’t follow the recommendations for either financiers or the almond cake and baked it in a clear pan. This was probably a mistake, as glass pans do not conduct heat as well as metal ones (Lawandi, J.).

Financiers are most typically baked in individual molds. Royal Baking Powder specifies a fluted pan, which I don’t own. I thus didn’t follow the recommendations for either financiers or the almond cake and baked it in a clear pan. This was probably a mistake, as glass pans do not conduct heat as well as metal ones (Lawandi, J.).

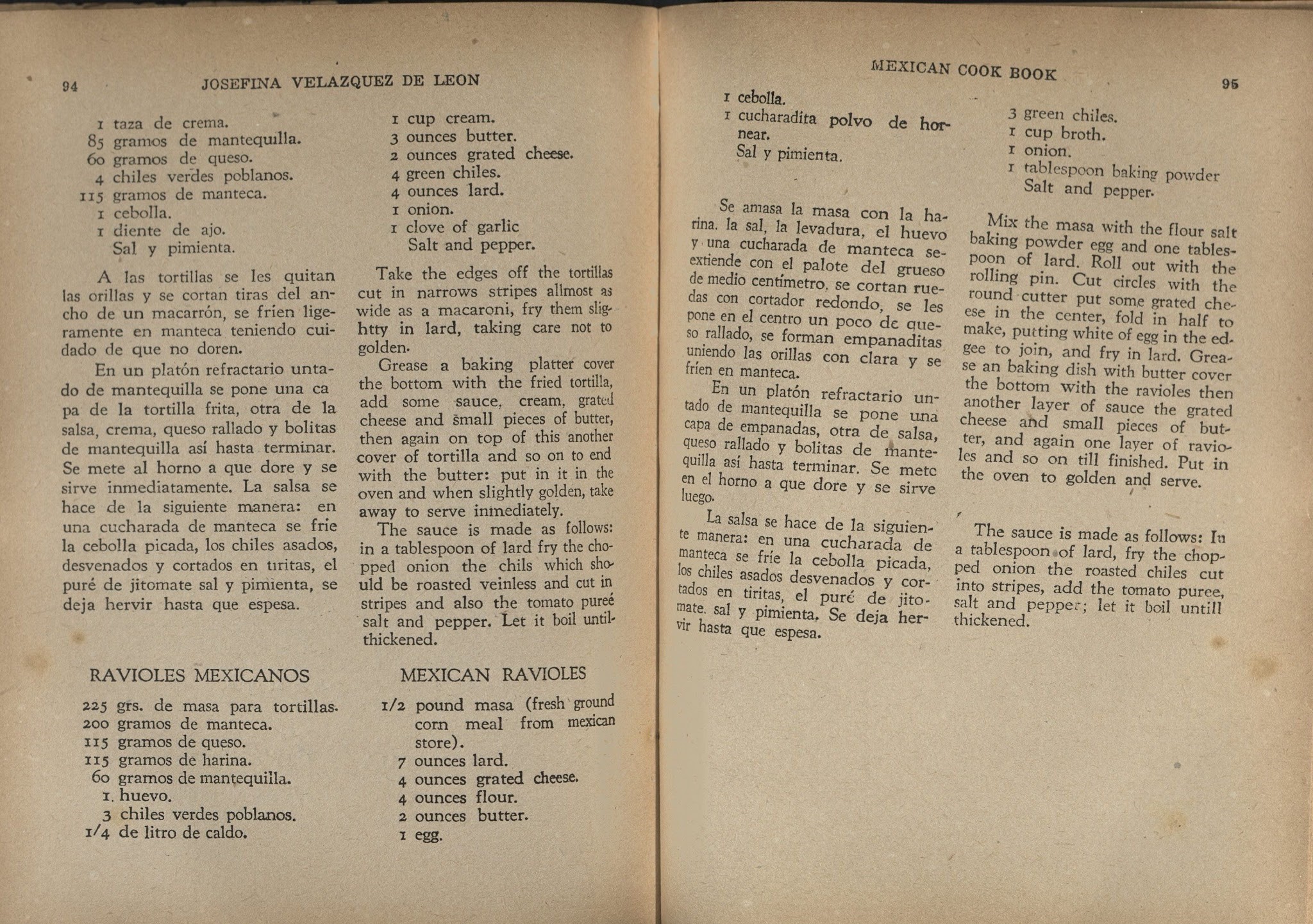

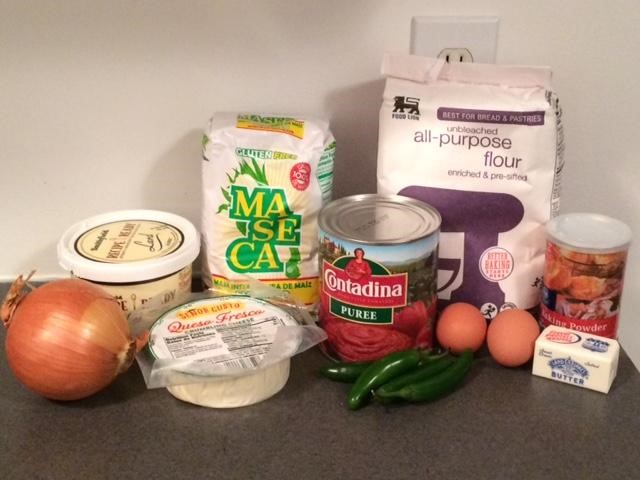

If the E. coli outbreak at Chipotle has you looking for a new way to satisfy your cravings or if you are simply hoping to make a step up from those late night Taco Bell runs, then this post is for you. If you have a hankering for warm cheese and fried foods (and who doesn’t?), Josefina Velazquez de Leon and her

If the E. coli outbreak at Chipotle has you looking for a new way to satisfy your cravings or if you are simply hoping to make a step up from those late night Taco Bell runs, then this post is for you. If you have a hankering for warm cheese and fried foods (and who doesn’t?), Josefina Velazquez de Leon and her

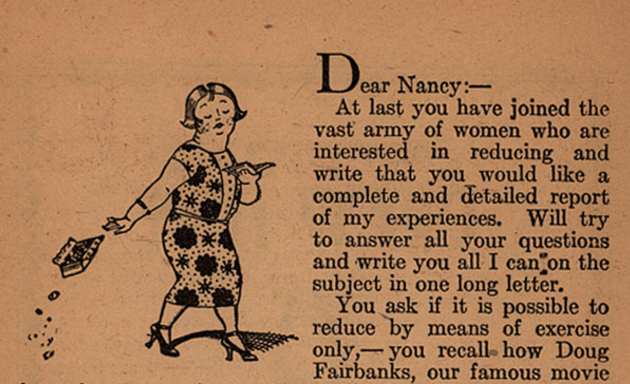

New Years Eve marked the final celebration in a slew of winter holidays that put my more introverted side through the social ringer. With New Year’s resolutions on my mind, I am eager to settle back into the routine that unraveled during the holidays (perhaps with a few more trips to the gym during the week). More than anything, I want to “get back to normal” and recharge.

New Years Eve marked the final celebration in a slew of winter holidays that put my more introverted side through the social ringer. With New Year’s resolutions on my mind, I am eager to settle back into the routine that unraveled during the holidays (perhaps with a few more trips to the gym during the week). More than anything, I want to “get back to normal” and recharge.

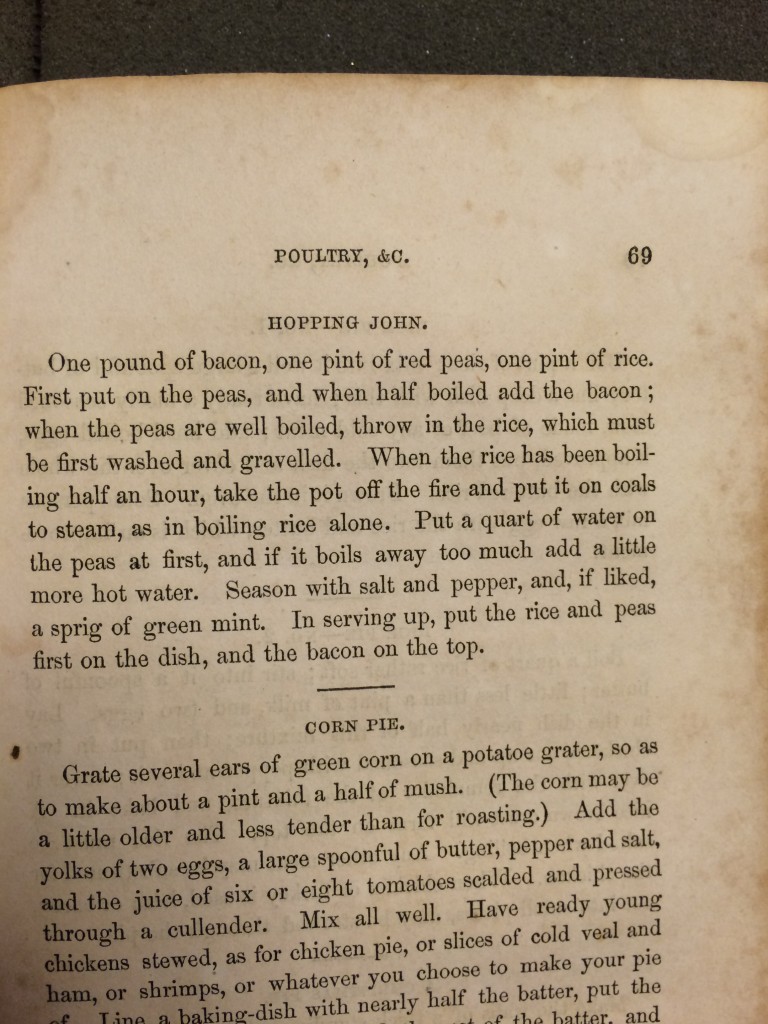

Instead of just placing sprigs of mint on top like a garnish, we decided to slice them into shreds to help bring out the flavor. The experiment paid off. The sharp soprano sweetness of the herb cut against the walking bass notes of the simple grain and savory fat. The end result was a meal that made us feel plenty lucky, if only to have leftovers to go around.

Instead of just placing sprigs of mint on top like a garnish, we decided to slice them into shreds to help bring out the flavor. The experiment paid off. The sharp soprano sweetness of the herb cut against the walking bass notes of the simple grain and savory fat. The end result was a meal that made us feel plenty lucky, if only to have leftovers to go around.

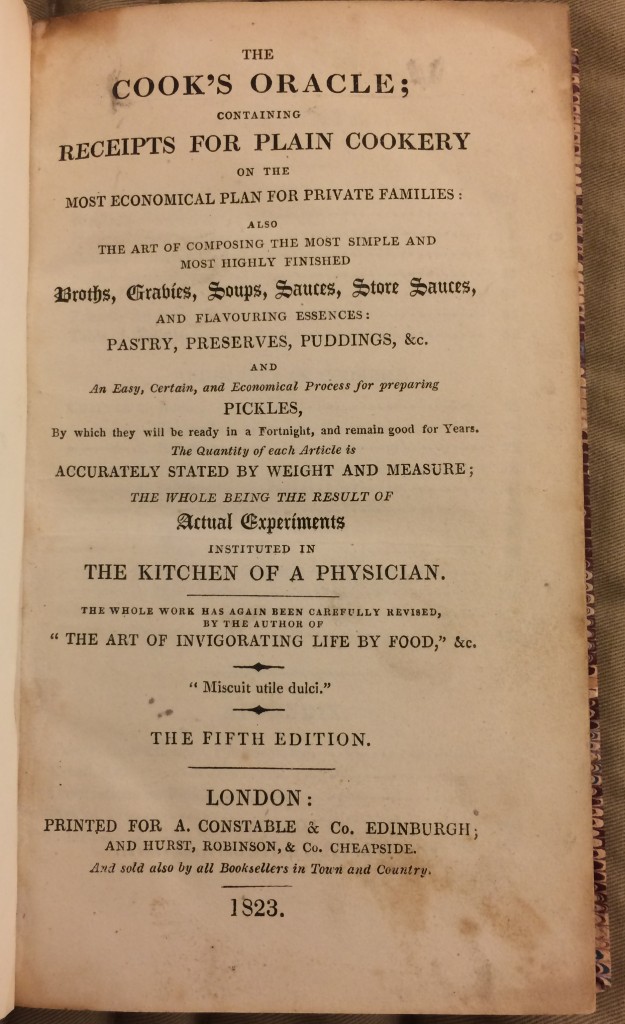

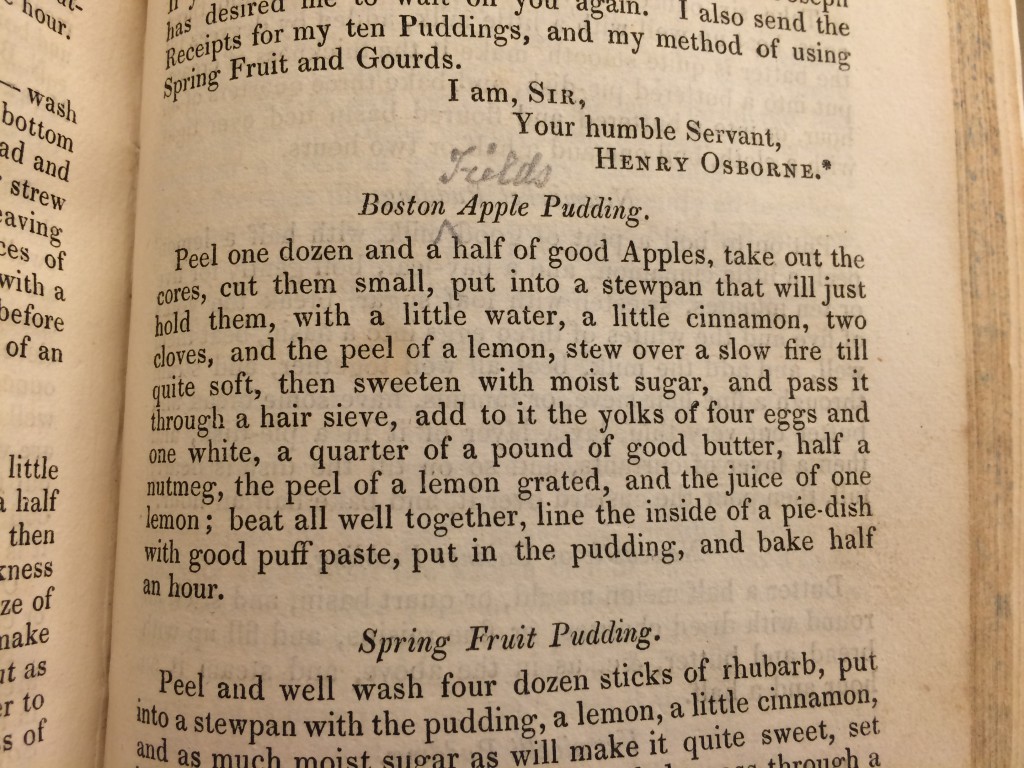

The Cook’s Oracle was a bestseller when it was first published in 1817. Its author, William Kitchiner (1775-1827), was a household name in England at the time, and was known for being an atypical host to his dinner guests – he prepared the food rather than his staff and even did the cleaning up as well. In addition to being an avid cook and successful cookbook author, Kitchiner was also an optician and inventor of telescopes, which perhaps explains why this particular cookbook is in the History of Medicine Collections here at Duke.

The Cook’s Oracle was a bestseller when it was first published in 1817. Its author, William Kitchiner (1775-1827), was a household name in England at the time, and was known for being an atypical host to his dinner guests – he prepared the food rather than his staff and even did the cleaning up as well. In addition to being an avid cook and successful cookbook author, Kitchiner was also an optician and inventor of telescopes, which perhaps explains why this particular cookbook is in the History of Medicine Collections here at Duke.

The apples actually cooked down pretty quickly – it probably took less than thirty minutes in total. I didn’t know what “moist sugar” is, but it turns out it is

The apples actually cooked down pretty quickly – it probably took less than thirty minutes in total. I didn’t know what “moist sugar” is, but it turns out it is

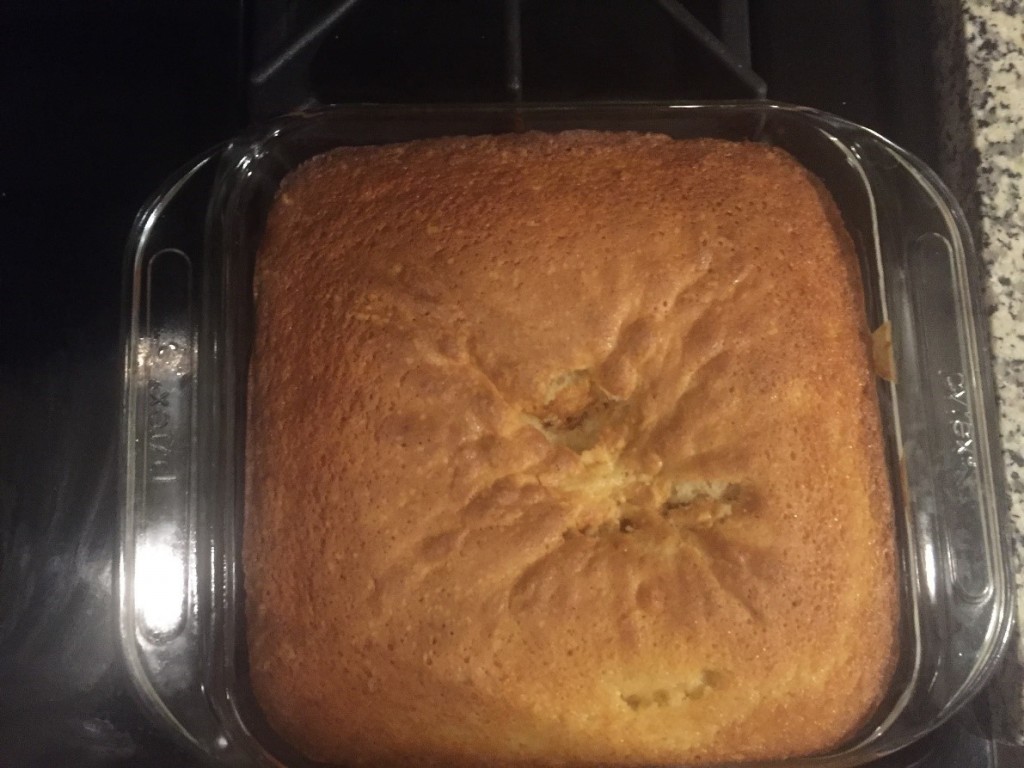

We mixed in the butter, eggs, and lemon zest. For the crust, I used a sheet of puff pastry, but since puff pastry is square, I used some of the other sheet of puff pastry to fill in the missing pieces. As you can see below, it ended up looking like a giant flower!

We mixed in the butter, eggs, and lemon zest. For the crust, I used a sheet of puff pastry, but since puff pastry is square, I used some of the other sheet of puff pastry to fill in the missing pieces. As you can see below, it ended up looking like a giant flower!