New Years Eve marked the final celebration in a slew of winter holidays that put my more introverted side through the social ringer. With New Year’s resolutions on my mind, I am eager to settle back into the routine that unraveled during the holidays (perhaps with a few more trips to the gym during the week). More than anything, I want to “get back to normal” and recharge.

New Years Eve marked the final celebration in a slew of winter holidays that put my more introverted side through the social ringer. With New Year’s resolutions on my mind, I am eager to settle back into the routine that unraveled during the holidays (perhaps with a few more trips to the gym during the week). More than anything, I want to “get back to normal” and recharge.

Whereas I am cozying up for the long, comfortingly mundane winter, New Orleanians are gearing up for the most magical time of year: Mardi Gras season. That’s right. I said season. Unbeknownst to many, Mardi Gras is not just a day, it’s a weeks-long celebration marked by cloudless skies, community parades, and good street food.

Although Mardi Gras day jumps around from year to year depending on Easter, the season always kicks off on January 6, or the Epiphany – the day in the Christian religious tradition when the three wise men visited Christ, bringing gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. In New Orleans, community members consume brightly colored King Cakes to celebrate the start of the Mardi Gras season.

What is a King Cake? According to the 5th edition of The Picayune’s Creole Cook Book (1916), which we have in our collection at the Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, a King Cake is:

[…] a Creole cake whose history is the history of the famous New Orleans Carnivals celebrated in song and stories. The “King’s Cake,” or “Gateau de Roi,” is inseparably connected with the origin of our now world-famed Carnival balls. In fact, they owe their origin to the old Creole custom of choosing a king and queen on King’s Day, or Twelfth Night. In old Creole New Orleans, after the inauguration of the Spanish domination and the amalgamation of the French settlers and the Spanish into that peculiarly chivalrous and romantic race, the Louisiana Creole, the French prettily adopted many of the customs of their Spanish relatives, and vice versa. Among these was the traditional Spanish celebration of King’s Day, “Le Jour des Rois,” as the Creoles always term the day. King’s Day falls on January 6, or the twelfth day after Christmas, and commemorates the visit of the three Wise Men of the East to the lowly Bethlehem manger. This day is still even in our time still the Spanish Christmas, when gifts are presented in commemoration of the Kings’ gifts. With the Creoles it became “Le Petit Noël,” or Little Christmas, and adopting the Spanish custom, there were always grand balls on Twelfth Night; a king and a queen were chosen, and there were constant rounds of festivities, night after night, till the dawn of Ash Wednesday. From January 6, or King’s Day, and Mardi Gras Day became the accepted Carnival season. Each week a new king and queen were chosen and no royal rulers ever reigned more happily than did these kings and queens of a week.

Most New Orleanians buy their cakes from a local bakery – each baker making and decorating the cake in a slightly different way. Ask a New Orleanian where he or she gets his or her King Cake and they will proudly claim their allegiance to a particular bakery. Clearly, in New Orleans, not all King Cakes are made the same.

There is, however, some standardization. New Orleans-style King Cakes are braided yeast breads with deep pools of white icing, dusted with purple, green, and yellow granulated sugar. Those colorful sugar crystals represent justice, faith, and power, respectively. As is the case with most traditional dishes, there are, of course, spin-offs. One of my favorites is the iridescent delight from Sucré up on Magazine Street. Others, like Cake Café, decorate their cakes in a Jackson Pollock-esque style.

The King Cake, then, is the prize item in a seasonal competition among New Orleans’ local bakeries. What stands out is the fact that King Cake is not really a dessert that New Orleanians make themselves. It is something that is purchased and happily carted home in kitschy bakery boxes.

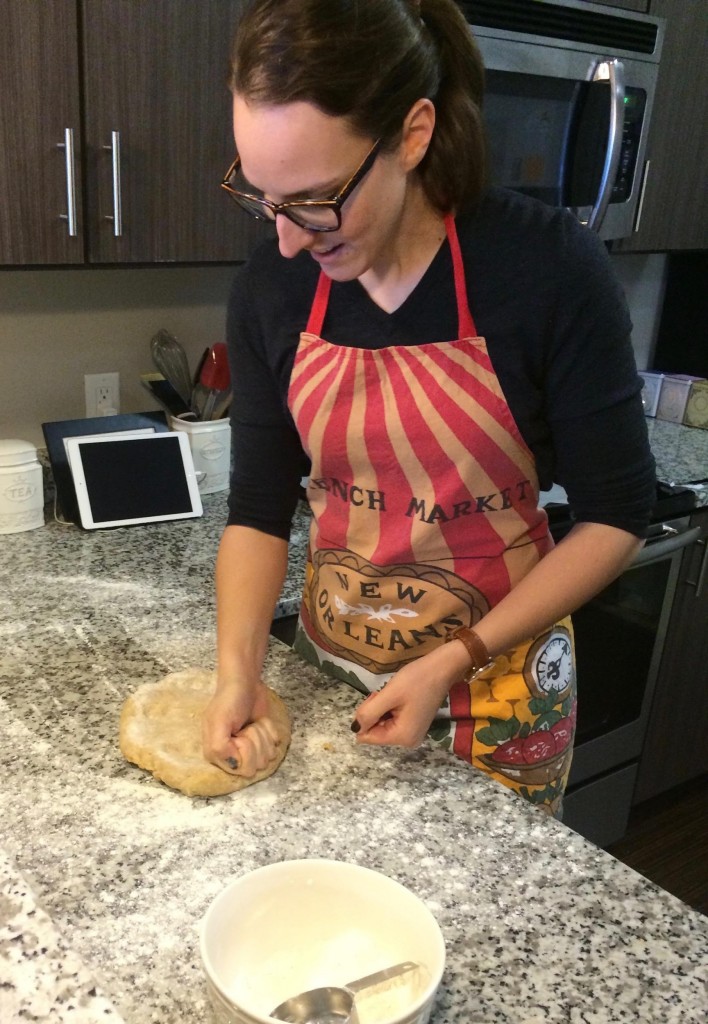

With the timing of my post in early January, I wanted to do a King Cake recipe for the Rubenstein Test Kitchen. Combing through the historic cookbooks in the Rubenstein collection, however, I was hard pressed to find a recipe for this sugary treat, which makes me wonder about its origins and its place in the home kitchen. Was the cake, if ever, made at home? Or was it always purchased? Although I could not find a recipe to work from, I had the description from the Picayune’s Creole Cook Book and I had ample experience eating King Cakes in New Orleans. The trick, then, was to find a modern recipe that drew upon traditional preferences for the texture, taste, and aesthetic of New Orleans’ most famous cake. I turned to the food editor of the Times-Picayune, Judy Walker, for guidance. She created an amalgam King Cake from numerous recipes, which can be found here. I further adapted the recipe, tweaking measurements here and there to suit the Durham climate. The major difference, though, was choosing to braid the dough rather than going for a simpler style, as Judy did. I am happy to say that I did not bake alone. My good friend, Lin Ong, who made a guest appearance in Pete Moore’s post last month, joined me. Together we set out to bring a little taste of New Orleans to Durham.

To make our culinary outing even more meaningful, I brought the memory and knowledge of my grandmothers into the kitchen. I used my grandmother Rosella’s hand mixer – a finicky appliance from the 1970s. It’s less effective than a stand mixer, to be sure. I like using it because she used it to make my favorite desserts. I also used my grandmother Jean’s rolling pin, another prized item in my kitchen. My hands felt too big on its bright red handles. The connection to my family, though, was more important to me than the utility of the object.

King Cake (adapted from Judy Walker’s recipe)

Ingredients:

4 to 4½ cups all-purpose flour

½ cup sugar

1 teaspoon salt

1 package instant yeast (RapidRise)

¾ cup whole milk

½ cup water

1 stick butter, plus 2 tablespoons melted butter

2 eggs

1 egg yolk

1 teaspoon lemon zest

1 tablespoon cinnamon, plus more for sprinkling

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

2 tablespoons powdered sugar

Procedure:

In a saucepan, heat milk, water, and butter to 120 degrees (use a candy thermometer to read the temperature).

In a mixing bowl, combine 1½ cups flour with the sugar, salt, and yeast.

Add heated liquid mixture to the bowl and beat 2 minutes at medium speed with an electric mixer.

Add the eggs, the egg yolk, ½ cup flour, lemon zest, cinnamon, nutmeg, and vanilla. Beat on high speed for 2 minutes. Stir in the remaining 2½ to 3 cups flour to make a stiff batter. You want it to be cohesive enough to braid, but sticky enough to stretch easily.

Cover the bowl tightly with plastic wrap and refrigerate for 2 hours. As Judy notes, “Yes, this is an unorthodox step to refrigerate the dough at this point, but it works with the instant rise yeast.”

Line a baking sheet with parchment paper.

Place the dough on a lightly floured surface and punch it down. Shape it into a roughly flattened rectangle.

With a floured rolling pin, roll out the dough to about ¼ inch thick, making a large rectangle roughly 24 inches long and 8 to 12 inches wide.

With a pastry brush, spread the melted butter over the surface of the dough.

Sift the powdered sugar and cinnamon into a small bowl. Sprinkle evenly over the buttered surface of the dough.

Fold the dough in half. Trim the rough edges away so as to make a proper rectangle. Divide and cut the dough into three even segments.

On a lightly floured surface roll these segments into long bands. Line the segments up and braid the dough, bringing the ends together to form a ring. Pinch the ends together to firmly connect the ring.

Transfer the braided roll to the baking sheet covered with parchment paper. Cover the cake with a clean dishtowel and let rise in a warm spot until doubled in size, about 1 hour.

Preheat the oven to 375 degrees. Bake until golden brown, about 20 minutes. Let the cake rest on the pan for 5 minutes, then carefully remove the cake and place on baking rack to cool completely before decorating.

Icing

Ingredients:

2 cups powdered sugar

5 tablespoons liquid, including 3 tablespoons lemon juice and 2 tablespoons milk

Gel food coloring (purple, green, and yellow)

Procedure:

Combine powdered sugar, lemon juice, and milk. Consistency is important. (I decided to drizzle my icing in the style of Cake Café. I used gel coloring. I dipped the end of a chopstick into the gel and vigorously mixed the coloring into the icing. I used a fork to drizzle the icing onto the cake: purple, green, and then gold. I let each color set before adding the next one. I topped the cake off with chunky sugar crystals).

After finishing up the cake, Lin was kind enough to make dinner for us. Embracing the spirit of New Orleans, I fixed us Sazerac cocktails and pulled out some Mardi Gras beads and lucky coins. It was a perfect ending to a spirited and joyous day of cooking. Laissez les bons temps rouler!

Post contributed by Ashely Young, Research Services Intern

Fantastic writeup! And the King Cake turned out so well — a really lovely bread swirled with cinnamon and just slightly sweetened by the icing. I ate some leftovers for breakfast the next day: toasted, buttered, with a mug of hot milky coffee.

What a story! I especially like the citation of the ancient book, which I’d never imagine as the origin of the recipe. I lived two years in the Big Easy and I thought I knew enough well about King cake until I ran into this by accident. Thank you Rubenstein Library!