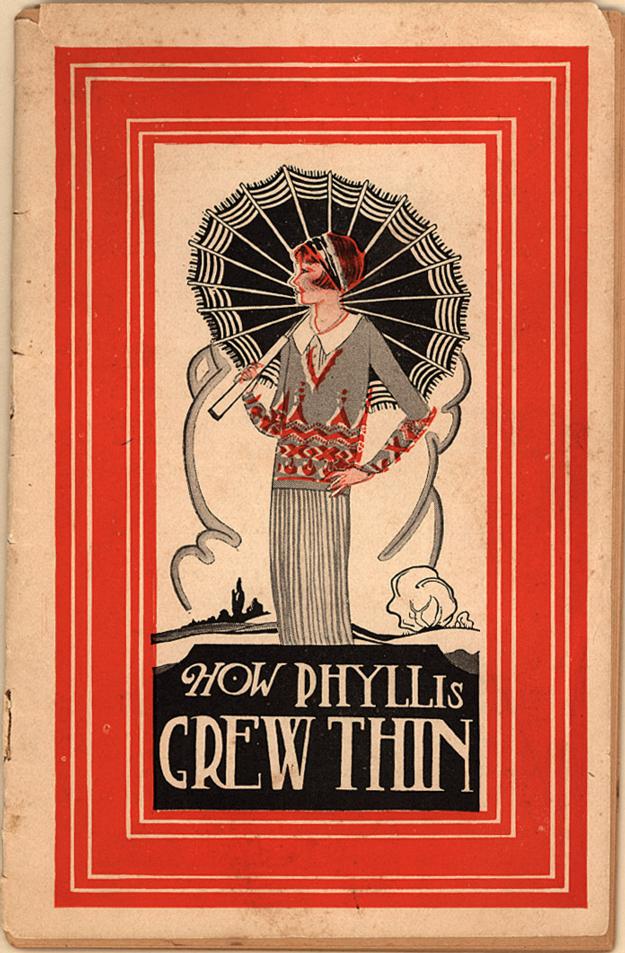

Browsing our digitized collections for Test Kitchen fodder on the recent snow day, I stumbled upon an item from the Emergence of Advertising in America project, How Phyllis Grew Thin, created by the Lydia E. Pinkham Medicine Company and published circa the 1920s. On the advertisement’s cover, Phyllis shields her rosy complexion with a parasol as she gazes off the page, inviting the reader to discover the secret to achieving the willowy frame holding up her stylish sweater and pleated skirt. We open the booklet and find stories of how women can shed undesired pounds through a reduced diet and relieve menstrual cramps, cycle irregularities, and menopausal symptoms through the use of Lydia E. Pinkham’s products.

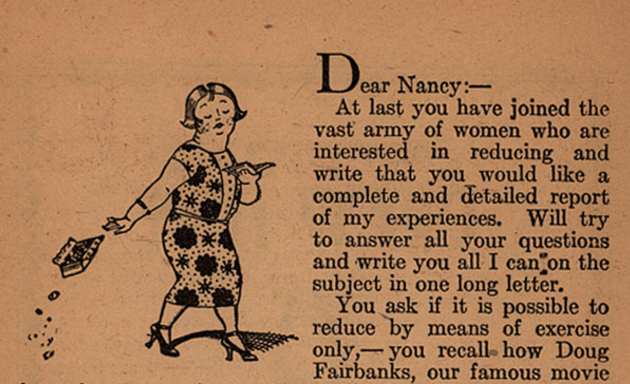

The epistolary advertisement is addressed to Nancy, a pudgy cartoon foil to Phyllis’s elegant watercolor. Phyllis promises to share with Dear Nancy the keys to losing weight through a proper diet. We learn that Phyllis has not always been so effortlessly thin. Inspired by Douglas Fairbanks’ and President Taft’s weight loss, Phyllis determines to do the same. As soon as she announced her intention to lose weight, “the derision and ridicule of my family strengthened me in my determination.” (page 2) In addition to the nourishing fire that comes from wanting to prove someone wrong, her reduced-calorie diet consisted of “plain meat without butter or gravies,” corn, prunes, and the occasional crustless pie. (page 2) This kind of confessional tone continues to be a mainstay in contemporary weight loss advertising. The letter from Phyllis to Nancy serves as a precursor to current weight loss advertising’s penchant for before-and-after photos, Instagram hashtag culture (check out #transformationtuesday and #fitspo), and celebrity-endorsed diets. (After a few Google searches for weight loss advertisements, my Facebook feed populated with sponsored content promising me a smaller pant size in mere days.)

Though her crash diet kept the weight off for a few years, Phyllis eventually gained the weight back and got serious about counting calories as a way to reduce again. She shares with Nancy that “it is not necessary for you to know just what a calorie is so long as you remember not to eat foods containing too many of them.” (page 3) The suggested calorie intake is considerably lower than most contemporary diet plans recommended by nutritionists, advising that Nancy (and “the army of women who are interested in reducing”) consume 1000-1200 calories a day. Phyllis then advises Nancy to take Lydia E. Pinkham’s Liver Pills and Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound, claiming that they help alleviate constipation and excessive nervousness, respectively. Lydia E. Pinkham established the Lydia E. Pinkham Medicine Company in 1873. Its signature product, Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound, was a tincture of “black cohosh, life root, unicorn root, pleurisy root, fenugreek seed, and a substantial amount of alcohol” formulated to ease menstrual cramps and menopausal symptoms (1). Pinkham’s products still line shelves today, each box featuring Lydia Pinkham’s face, promising relief.

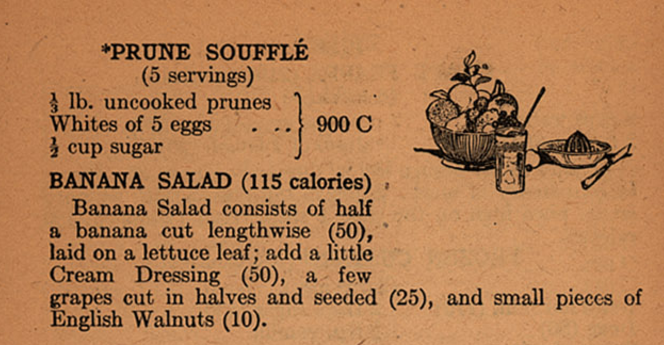

At the top of each page, the booklet provides a daily meal plan with calorie counts for each item. The offerings are spare. One suggested breakfast consists of “4 saltines, 1 tbsp. cream cheese, 2 prunes, tea and lemon (without sugar).” (page 18) An idea for one dinner is little more than bun-less hot dogs and a small bowl of ice cream.

Faced with these choices, I considered upping the Test Kitchen ante by following one of the suggested meal plans for a few days. Upon reflection, I thought better and opted to spare my friends and colleagues the monster that I am when not eating enough at regular intervals. Even reading meal plans for day after day of fruit (or saltines!) for breakfast followed by a mayonnaise-laden lunch had me throwing my Phyllis-esque determination out the window. The booklet contained few actual recipes. Oddly, most of them were for desserts: frosting, Brown Betty, orange sherbet, and pudding. The dessert that caught my eye, though, was prune soufflé. Why? Frankly, it sounded so unappetizing that I felt compelled to give it a shot. Maybe I’d been missing its hidden appeal. And, having never tried to make a soufflé, it seemed a fun technical challenge.

The recipe given by the advertisement is deceptively simple. It’s less a recipe and more a list of ingredients. Perhaps this suggests that Pinkham’s target customer already had a thorough knowledge of soufflé-making and would simply need the inspiration to try a new take on the dessert. Since I have no such skills, I turned to the internet as a supplement, sourcing tips from a 1998 issue of Gourmet.

When beginning a cooking project, I recommend ensuring you have all the right tools at your disposal before cracking your eggs. Alas, I did not follow my own advice! I began my soufflé only to find that my house apparently lacks a hand mixer. Already committed to the recipe, I decided to channel my foremothers and hand-whip the eggs into stiff peaks. If cooks beat eggs into submission for years by hand, then surely I could as well! All those hours spent practicing surya namaskara should be good for something, right?

Unfortunately, I underestimated the time and effort needed to beat the eggs into fluffy mountains. I achieved the early stage, a frothy foam, but never progressed to the stiff peaks a soufflé needs to bloom. Still, it was late and I had cracked five eggs to try to make this work, so I soldiered on. Per Gourmet’s instructions, I had soaked the chopped prunes in hot earl grey tea and lemon zest, hoping to brighten the flavors. After pureeing and cooling them, I slowly folded the foam into the mixture. Uneven in color, bubbly, and flat, I knew things had taken a turn for the worse. Still, I slid the muffin tin into the oven anyway, hoping that even if the souffle didn’t rise, I’d end up with a sweet baked egg fluff?

Sixteen minutes later, I pulled them out of the oven to find a sad, deflated pan of brown blobs. I tasted one, and suddenly understood how easy it would be to “reduce” while following this diet. I tossed the remnants and dosed myself with a small handful of chocolate chips, the rest of which will hopefully go into a more successful baking project.

Post contributed by Katrina Martin, Technical Services Assistant.

![Maria Sibylla Merian. De europische insecten. Tot Amsterdam: by J.F. Bernard, [1730].](https://blogs.library.duke.edu/rubenstein/files/2016/01/merian.jpg)

New Years Eve marked the final celebration in a slew of winter holidays that put my more introverted side through the social ringer. With New Year’s resolutions on my mind, I am eager to settle back into the routine that unraveled during the holidays (perhaps with a few more trips to the gym during the week). More than anything, I want to “get back to normal” and recharge.

New Years Eve marked the final celebration in a slew of winter holidays that put my more introverted side through the social ringer. With New Year’s resolutions on my mind, I am eager to settle back into the routine that unraveled during the holidays (perhaps with a few more trips to the gym during the week). More than anything, I want to “get back to normal” and recharge.

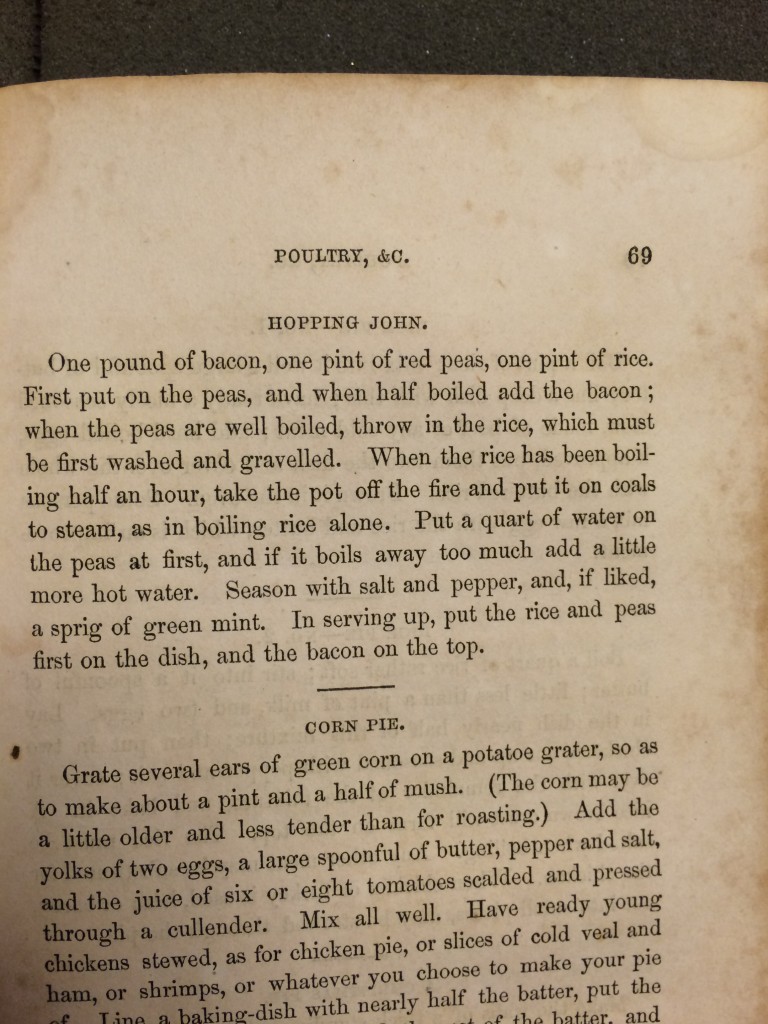

Instead of just placing sprigs of mint on top like a garnish, we decided to slice them into shreds to help bring out the flavor. The experiment paid off. The sharp soprano sweetness of the herb cut against the walking bass notes of the simple grain and savory fat. The end result was a meal that made us feel plenty lucky, if only to have leftovers to go around.

Instead of just placing sprigs of mint on top like a garnish, we decided to slice them into shreds to help bring out the flavor. The experiment paid off. The sharp soprano sweetness of the herb cut against the walking bass notes of the simple grain and savory fat. The end result was a meal that made us feel plenty lucky, if only to have leftovers to go around.

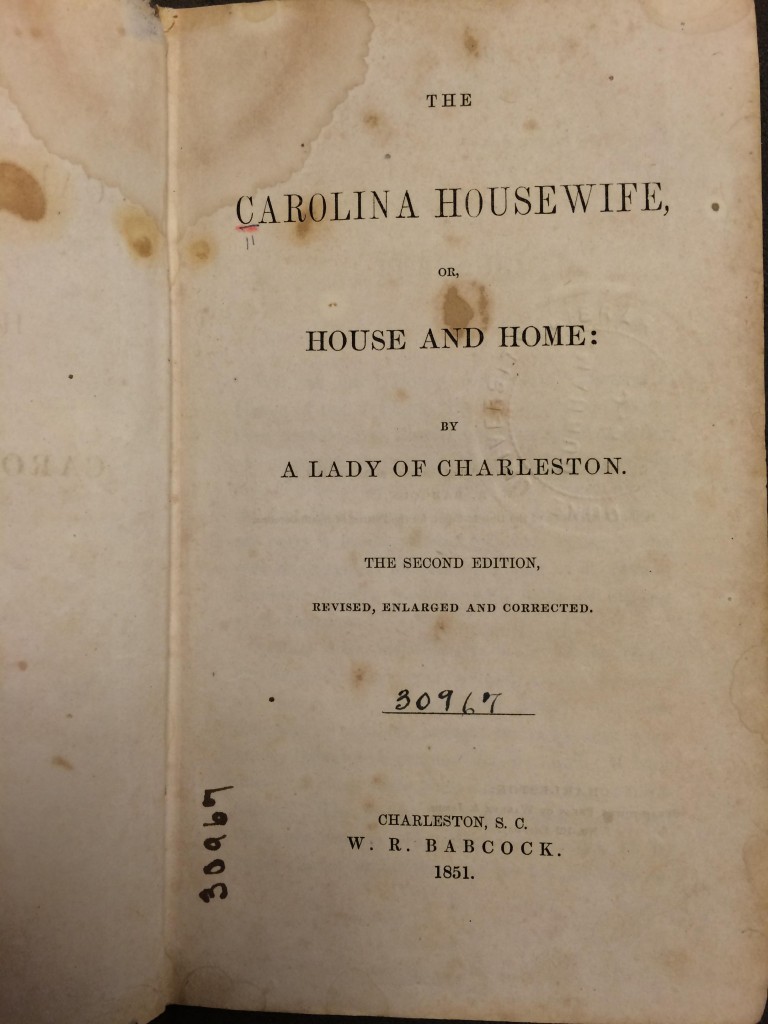

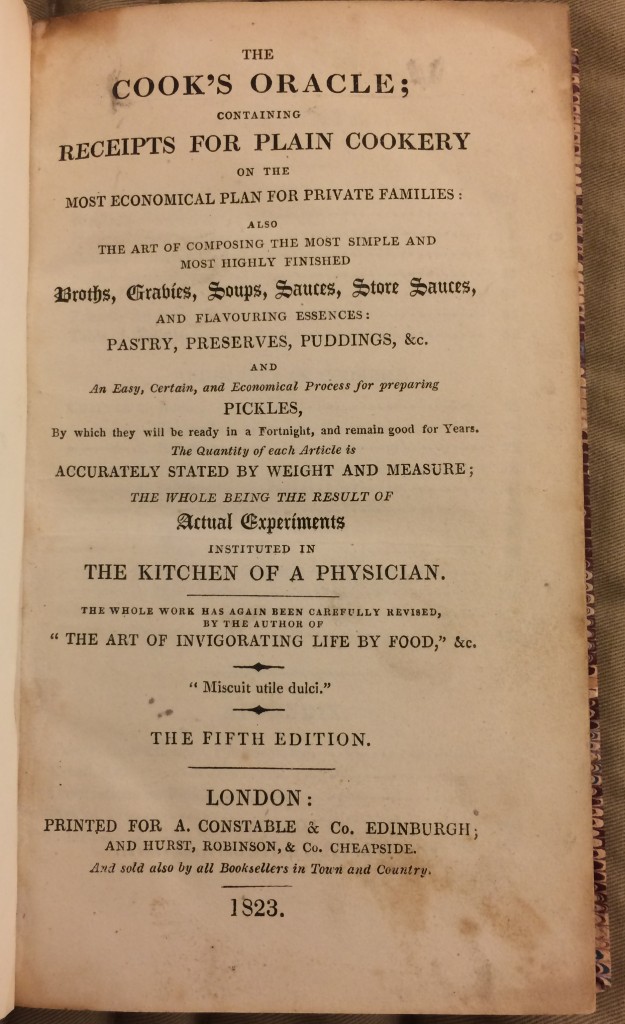

The Cook’s Oracle was a bestseller when it was first published in 1817. Its author, William Kitchiner (1775-1827), was a household name in England at the time, and was known for being an atypical host to his dinner guests – he prepared the food rather than his staff and even did the cleaning up as well. In addition to being an avid cook and successful cookbook author, Kitchiner was also an optician and inventor of telescopes, which perhaps explains why this particular cookbook is in the History of Medicine Collections here at Duke.

The Cook’s Oracle was a bestseller when it was first published in 1817. Its author, William Kitchiner (1775-1827), was a household name in England at the time, and was known for being an atypical host to his dinner guests – he prepared the food rather than his staff and even did the cleaning up as well. In addition to being an avid cook and successful cookbook author, Kitchiner was also an optician and inventor of telescopes, which perhaps explains why this particular cookbook is in the History of Medicine Collections here at Duke.

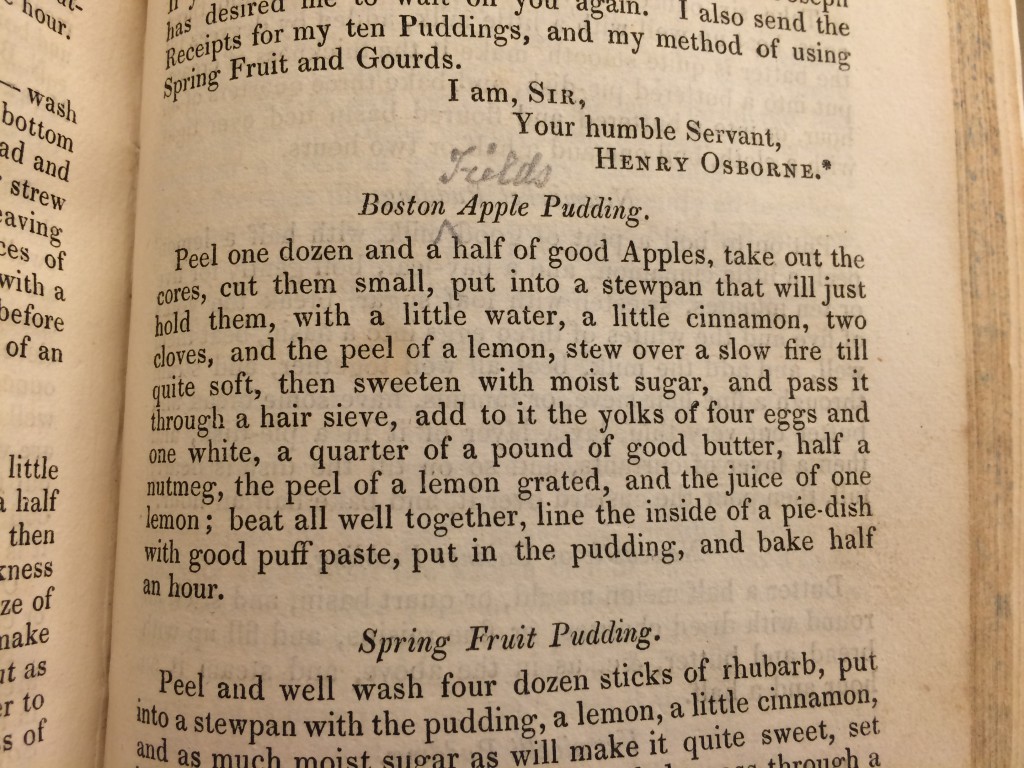

The apples actually cooked down pretty quickly – it probably took less than thirty minutes in total. I didn’t know what “moist sugar” is, but it turns out it is

The apples actually cooked down pretty quickly – it probably took less than thirty minutes in total. I didn’t know what “moist sugar” is, but it turns out it is

We mixed in the butter, eggs, and lemon zest. For the crust, I used a sheet of puff pastry, but since puff pastry is square, I used some of the other sheet of puff pastry to fill in the missing pieces. As you can see below, it ended up looking like a giant flower!

We mixed in the butter, eggs, and lemon zest. For the crust, I used a sheet of puff pastry, but since puff pastry is square, I used some of the other sheet of puff pastry to fill in the missing pieces. As you can see below, it ended up looking like a giant flower!