Kelly Wooten, Research Services and Collection Development Librarian for the Sallie Bingham Center.

For over twenty years, the Rubenstein Library has offered travel grants for researchers. The first grant began with the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture’s Mary Lily Research Travel Grant program and grew to include the John Hope Franklin Research Center for African and African American History and Culture; John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History; History of Medicine Collections; Human Rights Archive; and most recently, the Harry H. Harkins T’73 Travel Grants for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender History.

As archivists, we have long understood that research, scholarship, writing, and creative processes take time. The outcomes from the people and projects we support often come to fruition years in the future. Thankfully, we stay in touch with many of our grant recipients long after they visit the Rubenstein Library, and are thrilled to celebrate their publications and projects once they are out in the world. Here are a few selections we’d like to highlight:

Lindsey Beal, Mellon Faculty Fellow at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, received a History of Medicine travel grant in March 2016. Beal’s photographic work, Parturition, features History of Medicine Collections instruments and artifacts with a focus on obstetric and gynecological tools.

Little Cold Warriors: American Childhood in the  1950s by Victoria Grieve, Associate Professor of History at Utah State University, was published by the Oxford University Press in 2018. Dr. Grieve visited the Rubenstein Library in May 2016 as a Foundation for Outdoor Advertising Research and Education Fellow through the Hartman Center to use the Outdoor Advertising Association of America archives, the Garrett Orr papers, and the J. Walter Thompson Co. Writings and Speeches Collection.

1950s by Victoria Grieve, Associate Professor of History at Utah State University, was published by the Oxford University Press in 2018. Dr. Grieve visited the Rubenstein Library in May 2016 as a Foundation for Outdoor Advertising Research and Education Fellow through the Hartman Center to use the Outdoor Advertising Association of America archives, the Garrett Orr papers, and the J. Walter Thompson Co. Writings and Speeches Collection.

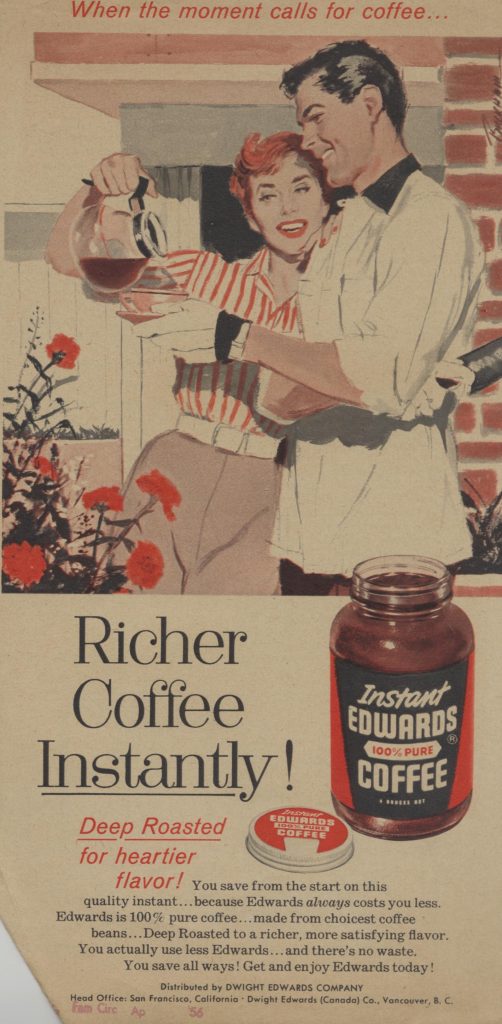

Her Neighbor’s Wife: A History of Lesbian Desire Within Marriage by Lauren Jae Gutterman, professor of American studies at the University of Texas at Austin, was published in 2019 by the University of Pennsylvania Press. Dr. Gutterman received a Mary Lily Research Travel Grant from the Bingham Center in 2013. Her research focused on the Minnie Bruce Pratt papers, as well as the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance’s archives and the papers of prominent feminist thinkers Robin Morgan and Kate Millett. Dr. Gutterman is also co-host of the podcast Sexing History.

Marjorie Lorch, Professor of Neurolinguistics, Department of Applied Linguistics and Communication, University of London, visited the Rubenstein Library in February 2018 as a History of Medicine Collections grant recipient, utilizing the Henry Charles Bastian papers for her research. Her article, “The long view of language localization” was published in Frontiers in Neuroanatomy in May 2019. She also co-authored an article with R. Whurr, “The laryngoscope and nineteenth-century British understanding of laryngeal movements,” Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, also published in May 2019.

Rachel R. Miller successfully defended her dissertation “The Girls’ Room: Bedroom Culture and the Ephemeral Archive in the 1990s” to complete her Ph.D. in English at the Ohio State University on May 18, 2020. She received a Mary Lily Research Grant to use the Bingham Center’s zine collections in 2018. Since her defense was held via videoconference, Dr. Miller noted on Twitter, “I’ve been working for four years on a project about how teenage girls’ bedrooms are archival spaces, so I guess it’s only appropriate that I’ll be defending my project from my bedroom.”

Erik A. Moore, postdoctoral associate at the University of Oklahoma’s Humanities Forum, visited the Rubenstein Library in May 2017 as a Human Rights Archive grant recipient. His article “Rights or Wishes? Conflicting Views over Human Rights and America’s Involvement in the Nicaraguan Contra War” was published in the journal Diplomacy & Statecraft (v. 29, no. 4) in October 2018. Dr. Moore used the Washington Office on Latin America records in his research.

Wangui Muigai, Assistant Professor in African and African American Studies and History at Brandeis University, is a historian of medicine and science. She received a Franklin Grant in 2015 for research on infant mortality and race from slavery to the Great Migration. Dr. Muigai was awarded the Nursing Clio inaugural prize for best journal article for “‘Something Wasn’t Clean’: Black Midwifery, Birth, and Postwar Medical Education in All My Babies” in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine (v. 93, no. 1,) in 2019, which cites an interview from the Behind the Veil oral history collection.

John Hervey Wheeler, Black Banking, and the Economic Struggle for Civil Rights by Brandon K. Winford, Assistant Professor of History at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville, was published by the University of Kentucky Press in 2019. . Dr. Winford is a graduate of North Carolina Central University and went on to receive his Ph.D. at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. He was awarded a Franklin Research Center grant in 2015-2016. While visiting the Rubenstein Library, Dr. Winford consulted the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company archive, the C.C. Spaulding papers, the Asa and Elna Spaulding papers, and the Rencher Nicholas Harris papers. In February 2020, Dr. Winford returned to Duke to give a talk about the book and his research at the Duke University Law School.

John Hervey Wheeler, Black Banking, and the Economic Struggle for Civil Rights by Brandon K. Winford, Assistant Professor of History at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville, was published by the University of Kentucky Press in 2019. . Dr. Winford is a graduate of North Carolina Central University and went on to receive his Ph.D. at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. He was awarded a Franklin Research Center grant in 2015-2016. While visiting the Rubenstein Library, Dr. Winford consulted the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company archive, the C.C. Spaulding papers, the Asa and Elna Spaulding papers, and the Rencher Nicholas Harris papers. In February 2020, Dr. Winford returned to Duke to give a talk about the book and his research at the Duke University Law School.

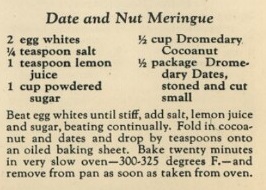

Crap: A History of Cheap Stuff in America by Wendy Woloson, Associate Professor of History, Rutgers-Camden, will be published by the University of Chicago Press in September 2020. Dr. Woloson visited the Rubenstein Library as a Hartman Center grant recipient in 2017 and used the Advertising Ephemera Collection and the Arlie Slabaugh Collection of Direct Mail Literature.

The Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library is pleased to announce the recipients of the 2020-2021 travel grants. Our research centers annually award travel grants to students, scholars, and independent researches through a competitive application process. We extend a warm congratulations to this year’s awardees. We look forward to meeting and working with you!

The Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library is pleased to announce the recipients of the 2020-2021 travel grants. Our research centers annually award travel grants to students, scholars, and independent researches through a competitive application process. We extend a warm congratulations to this year’s awardees. We look forward to meeting and working with you!

Questions? Please contact

Questions? Please contact