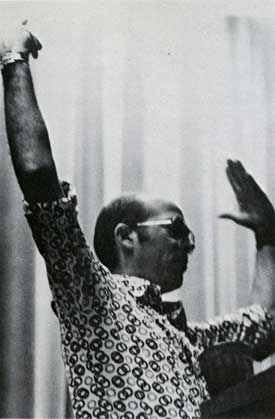

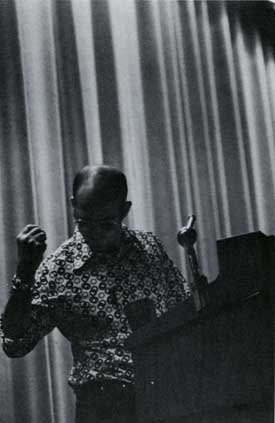

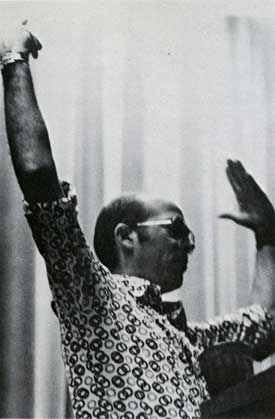

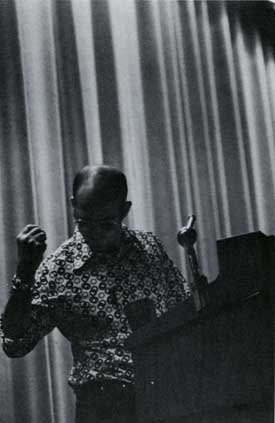

Hunter S. Thompson took the stage at Page Auditorium on October 22nd, 1974 at 8:50 PM. He was thirty five minutes late, visibly inebriated, and apparently quite unhappy to be there. He began his remarks to the packed auditorium of 1,500 saying, “I have no speech, nothing to say; I feel like a piece of meat.”

Hunter S. Thompson took the stage at Page Auditorium on October 22nd, 1974 at 8:50 PM. He was thirty five minutes late, visibly inebriated, and apparently quite unhappy to be there. He began his remarks to the packed auditorium of 1,500 saying, “I have no speech, nothing to say; I feel like a piece of meat.”

According to newspaper articles and editorials following the event, throughout the forty minutes Thompson remained onstage he dipped in and out of comprehensibility, exchanged insults and invectives with the audience, wrestled with a microphone, and bemoaned the lack of substance apparent in the questions written by the audience on 3×5 index cards. He read off one of the questions, “What is the happiest experience you’ve had in the past two weeks?” “That’s crap,” was the reply as he tossed the cards to the floor.

“Are you serious? The level of questions from this audience makes any sort of exchange completely impossible.”

As Thompson’s behavior appeared to become increasingly erratic, including asking himself questions and mumbling incomprehensible answers, worried administrators were having frantic discussions backstage attempting to decide how to handle the situation. At 9:05 they decided to let the speech continue and reevaluate the situation at 9:30. As 9:30 approached, Thompson began attempting to remove a fixed microphone from the podium in an effort to give it to an audience member asking a largely inaudible question about the rise of consumer politics. In failing to separate the microphone, he began wrestling with it, kicking the podium and the chairs onstage, and flung his bourbon onto the stage curtain. The bourbon was the final straw, and Linda Simmons, the Union program director, came on stage and asked him to leave. Although a third of the students attending had already left the auditorium, those remaining booed as Thompson left the stage, accusing the administration of curtailing free speech.

Out on the lawn behind the auditorium after the event, Thompson sat with over a hundred students for an hour and a half in a more informal setting before leaving the campus.

Out on the lawn behind the auditorium after the event, Thompson sat with over a hundred students for an hour and a half in a more informal setting before leaving the campus.

Over the next few days, several newspaper articles were written on the event, and many students sent letters to the editor both praising and decrying the appearance. The University refused to pay the speaking fee, claiming that Thompson had violated the terms of his contract. The decision was not contested by the marketing firm who had contracted Thompson for the event.

One letter to the editor, however, never saw the light of day: Thompson’s himself. Thompson’s side of the story, in all of its gonzo glory, is part of the records of the Major Speakers committee.

He starts with a description of his state of intoxication while writing the letter, and discloses his state of intoxication while getting onstage at Page. Settling down, he states he wants to set the record straight as to exactly what happened at “J.B. Duke’s carcinogenic citadel. . . . [his] Southern Sanctuary for wayward New Jersey lads.”

Surveying the audience, I found 3,000 youthful, transvestite politicos, clutching their law boards and caressing their left legs. I decided to hallucinate them into 3,000 animated (and horny) Okra plants so I could begin my speech, speaking Okraese (Too-Maa-Too) in my best drawl. . . . Suddenly I realized the microphone was a local cottonmouth with heparin-filled fangs. While wrestling with the snake, I sensed danger from the rear and quickly lit my handy glass of Bacardi 151 and ether and launched it at the curtain, ran outdoors and evacuated the Nicotinic city.

If you want to see Thompson’s full letter, the newspaper articles and editorials the appearance sparked, or any of the other Major Speakers records, they, and much more, are accessible at the Duke University Archives.

Post contributed by Matt Schaefer, Drill Intern for the Duke University Archives.

Trish Wheaton is CMO of Wunderman and Managing Partner of Y&R Advertising, two global marketing giants. In her role for both companies, Wheaton identified the untapped marketing opportunity around sustainability and now leads a cross-disciplinary sustainability consulting practice that works with major brands to tell their sustainability story credibly and compellingly.

Trish Wheaton is CMO of Wunderman and Managing Partner of Y&R Advertising, two global marketing giants. In her role for both companies, Wheaton identified the untapped marketing opportunity around sustainability and now leads a cross-disciplinary sustainability consulting practice that works with major brands to tell their sustainability story credibly and compellingly.