As someone who repairs books for a living, the idiom “don’t judge a book by its cover” can have a much more literal meaning than expected. I’m regularly encountering books that seem to need only one kind treatment from the outside, but then have more problems than I realized on the inside. This can be a bit frustrating when you’ve mentally prepared yourself for one kind of project and instead find yourself tackling more than you had planned for. Even so, it is especially satisfying to finish a treatment on a book that you felt was going to be complicated. In today’s blog, I’ll be sharing my most recent encounter with a book that I misjudged.

The Problem

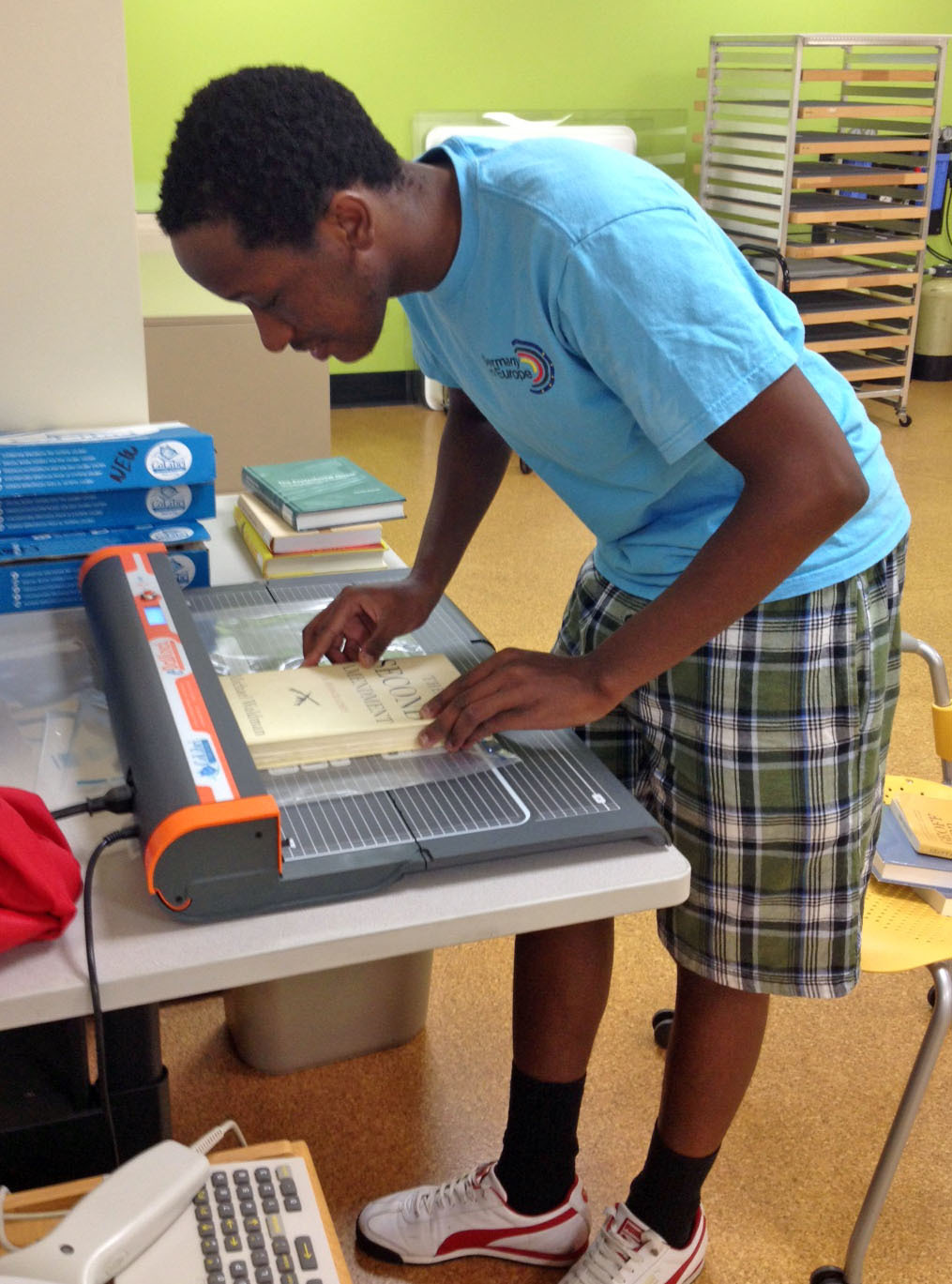

The Perkins Library has a great number of collections of Arabic books like the ones you see below.

These books are especially striking due to the eye-catching uniformity of their spines. Outside of how aesthetically pleasing they are, there is an added benefit to the fact that all the books are identical in design. Take a look at this collection of books below. Do any of them look different than the rest?

If you happened to notice the fourth book from the left in particular, then you can see what I meant earlier by “an added benefit”. Thanks to the collections precise design, it’s all the more obvious when something isn’t quite right.

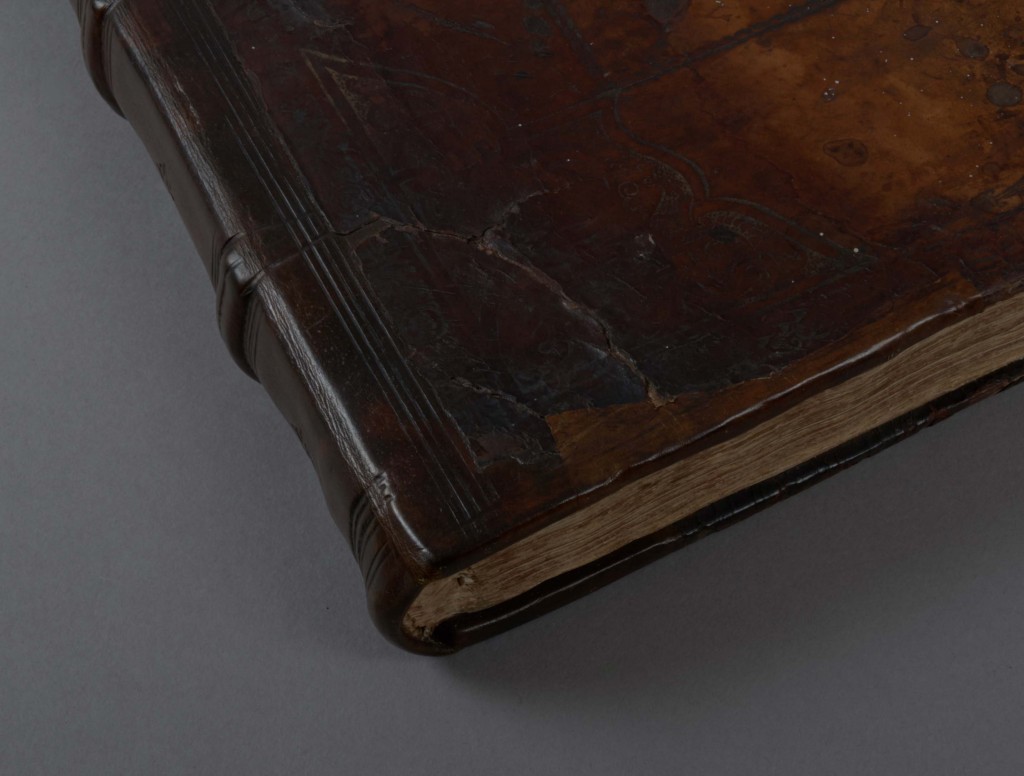

In this case, this poor book seems to have been crushed under something as well as torn along the spine. We certainly can’t leave the book to be handled by patrons in this state, so back to the lab it goes.

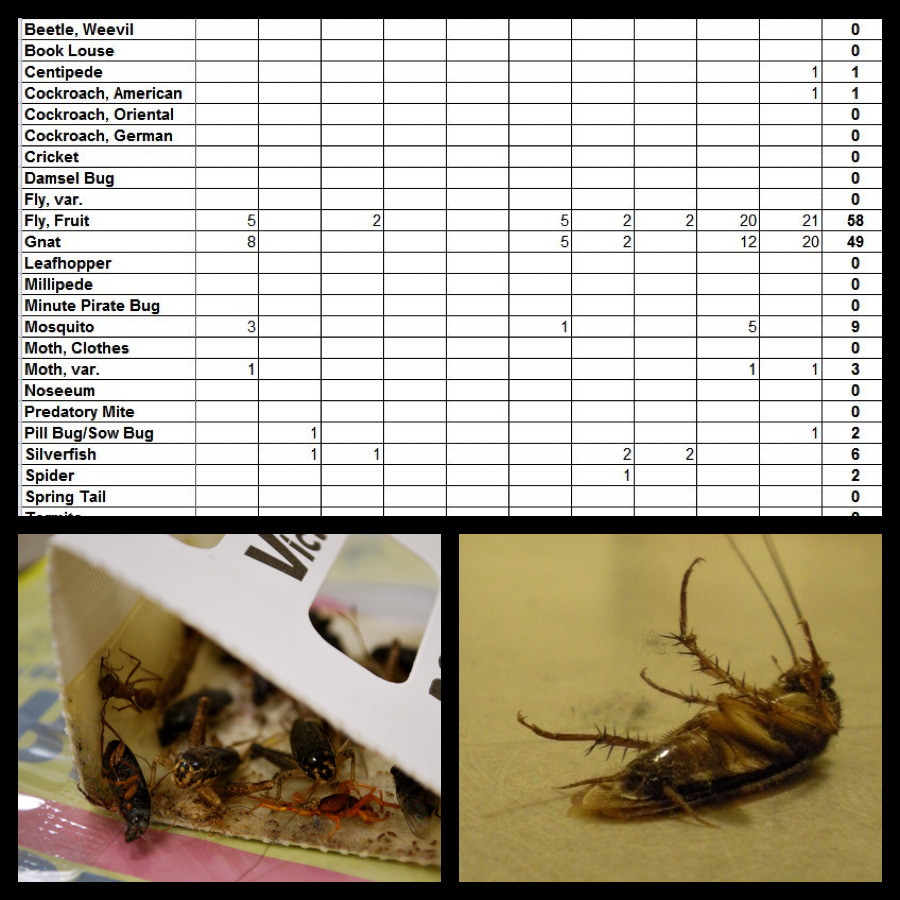

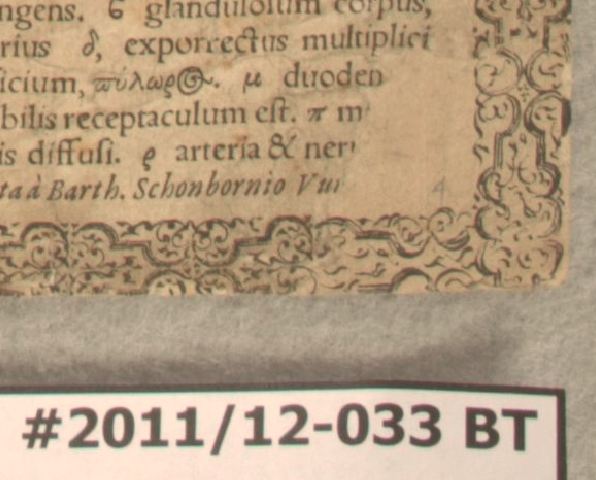

At this point, I had assumed the only problem I was dealing with was the crushed spine of the covers/textblock. Unfortunately for me, I didn’t realize that this book had been through more than just some extreme pressure. Right as you open the book to its title page, you’re greeted by discolored paper and some significant black speckling. The spotting continues a good 20 or so pages.

These are the tell-tale signs that not only did the book get wet at some point, but mold had made itself at home here as well.

Now, luckily this isn’t a terrible amount of mold to be dealing with. However, it does mean I have to add several more steps to my treatment before I can tackle the original issue of the crushed spine.

The Solution

Let’s say there hadn’t been any mold in this book. What would my treatment have looked like?

First, I would remove the covers so I could assess the damage done to the spine of the textblock. Once I had addressed that, I would prepare the textblock as I normally would for a recase. Finally, I would repair the covers by making a new spine piece to replace the damaged one, and reattached the textblock to the case.

Now, I will have to remove all of the mold first before I can start anything else.

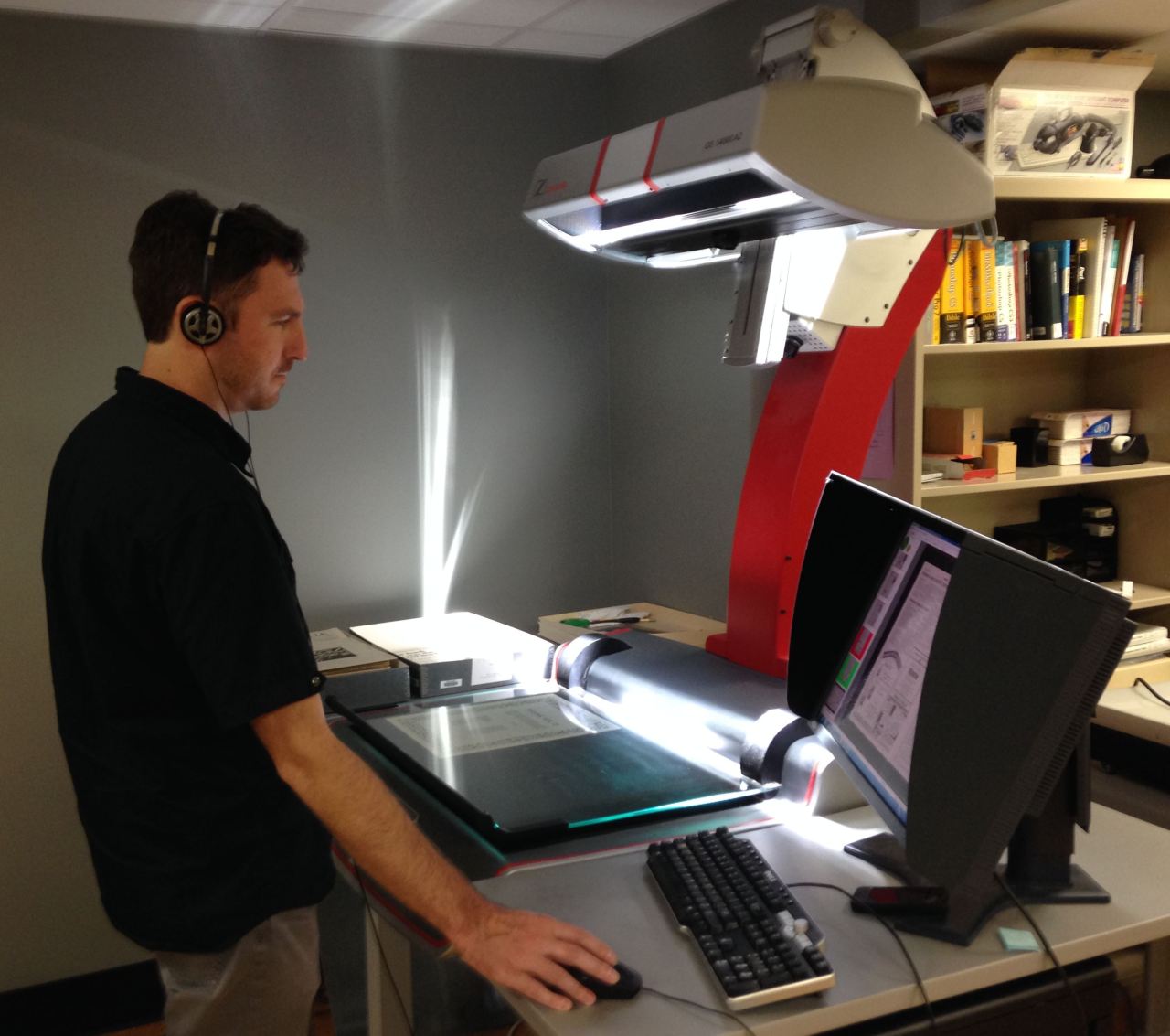

Based on the dry and powdery consistency of the mold, I can tell that it is no longer active and can be safely cleaned by hand. To do so, I used a soot sponge to manually clean the mold and debris off of every page.

You can see the immediate difference before and after using the sponge on the old mold, both on the pages and the sponge itself.

The soot sponge is mostly likely also picking up dirt and dust on the pages as well, but regardless it’s clear the book needed a good cleaning.

Now that the textblock is free of the residual mold, I can finally get to the treatment I had planned at the start. This book will be back on the shelves and ready for patrons in no time!