We recently published a blog post outlining our recent decision to drop Basecamp as a project management platform. Several people have asked us to share our new solution(s), and we thought we would take the opportunity to explain at a high level how we approached migrating away from Basecamp.

When DUL decided we would not be renewing our Basecamp subscription, there were about 88 active projects representing work across the entire organization. The owners of these projects would have just over two months to export their content and, if necessarily, migrate it to a new solution.

Exporting Content

Our first step was to form a 3-person migration team to explore different options for exporting content from Basecamp. We identified two main export options: DIY exporting and administrator exporting. For both options, we proactively tested the workflow, made screencasts, and wrote tutorials to ensure staff were well-prepared for either option.

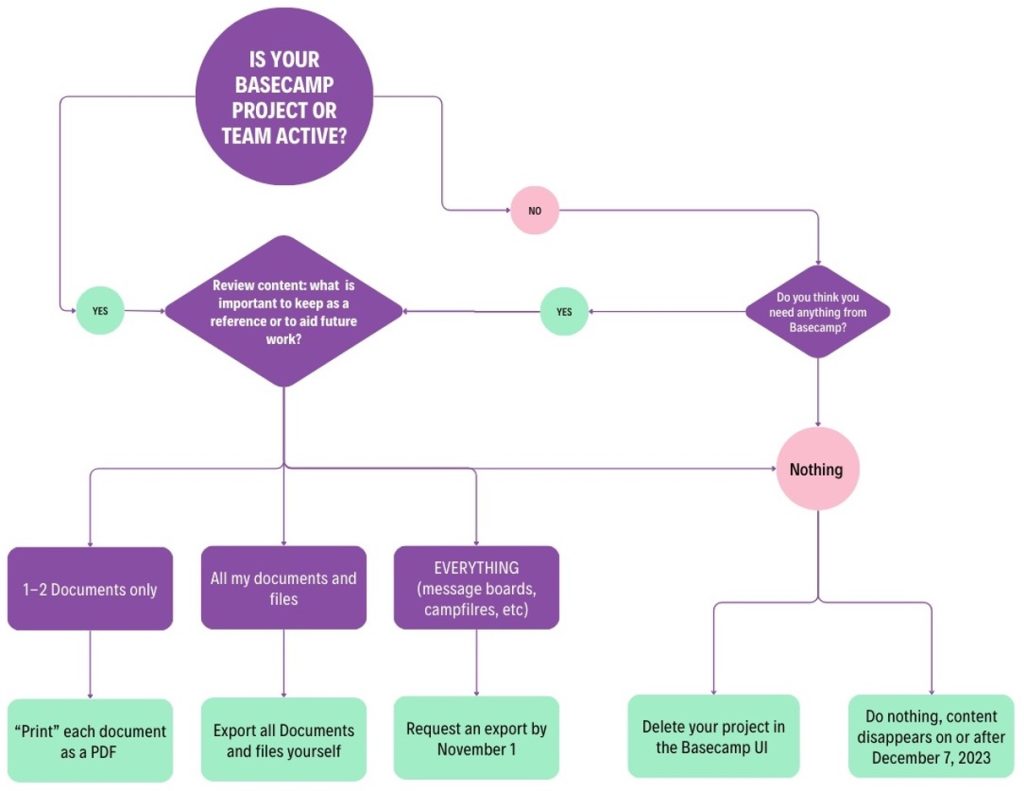

Before explaining the export options, however, we emphasized to staff that they should only export content that is needed for ongoing work or archival purposes. For completed projects that are no longer needed, we encouraged staff to “let it go.”

DIY exporting: We established that any member of a Basecamp project or team could export content from Basecamp. For projects that primarily used Basecamp to create documents or share files, we recommended they use the built-in export functionality within the Docs & Files section of the project. Project members could just go to Docs & Files, click the three dots menu in the upper-right corner, and select “Download this folder.” The download would include all of the same subfolders that were created in Basecamp. Basecamp documents would be saved as HTML files, and additional files would appear in their original format. One note, however, is that the HTML versions of the Basecamp documents would not include the comments added to those documents.

To export documents with their comments, or to export other Basecamp content like Message Boards or To-dos, another option was to save the individual pages as PDFs. While this took more time and didn’t work well for large and complicated projects, it had the added benefit of preserving the look-and-feel of the original Basecamp content. PDF was also preferable to HTML for some situations, like viewing the files in different file storage solutions.

Administrator exporting: If a team really needed a complete export of the current Basecamp content, an administrator for the Basecamp account could generate a full export. This type of export generated an HTML-based set of files that included all components of the project and any comments on documents. Every page available in Basecamp in the browser became a separate HTML file. With this export, however, the HTML files that were created for Docs & Files were stored in the same directory, all in a bunch. End users could still see subfolders when navigating the HTML files in a web browser, but the downloaded files weren’t organized that way anymore.

We decided not to track the DIY exporting but needed to organize the requests for administrator exporting as only a few accounts were “Basecamp Owners.” To organize and facilitate this process, we created an online request form for staff to complete.

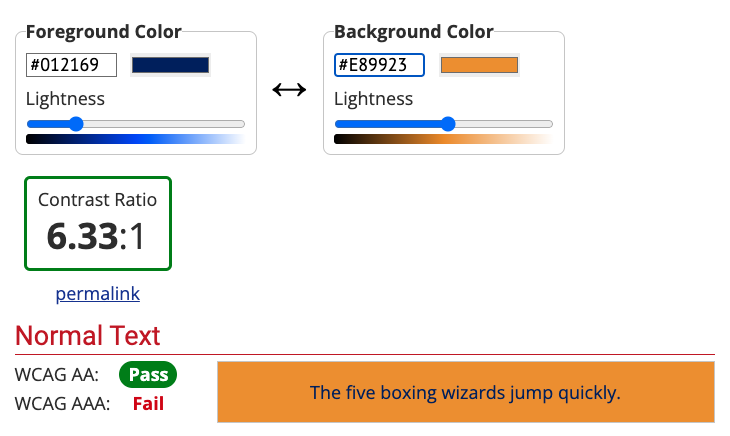

To help folks decide what they needed, we created a visual decision tree representing export options.

Alternative Project Management Tools

We realized early on that it was out of scope to complete a formal migration from Basecamp to one specific, alternate tool. We didn’t have staff capacity for that kind of project, and we weren’t inclined to prescribe the same solution for every project or team. To promote reliability and additional support systems, we encouraged teams to take advantage of enterprise solutions already supported by Duke University. The primary alternatives supported by Duke at this time were Box and MS Teams. Box had been in use in the Libraries for several years, but MS Teams was newer and not used in as widespread a manner across all staff.

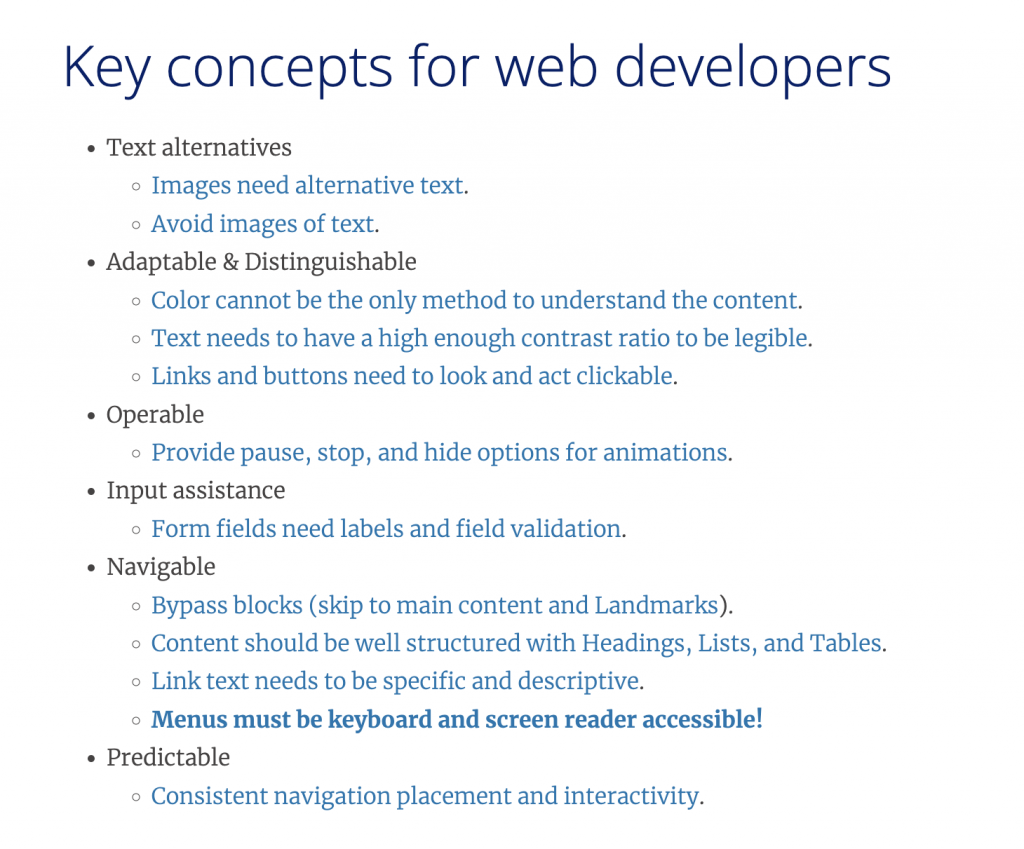

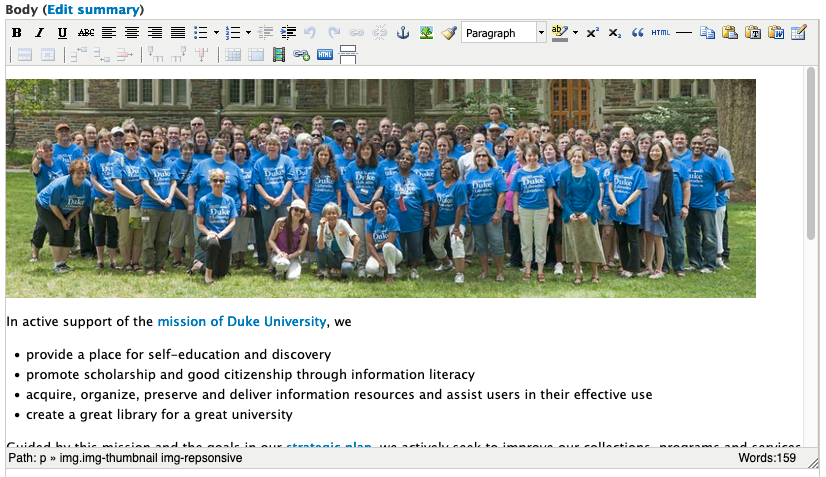

To help folks decide what tool they wanted to use, we created some documentation comparing the various features of Box and MS Teams with the functionality folks were used to in Basecamp. We also created screencasts that demonstrated how one can use Tasks in Box or the Planner app within Teams for managing projects and assignments.

| Basecamp | Teams | Box | Others |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campfire | Chat | Comments on Files, BoxNotes | |

| Message Board | Chat (can thread chats in Teams) | Comments on Files, Box Notes | |

| To-dos | Tasks by Planner and To Do | Task List | |

| Schedule | Channel Calendar, Tasks by Planner and To Do (timelines and due dates for tasks) | Task List (due date scheduling) | Outlook: Resource or Shared Calendar |

| Automatic Check-ins | |||

| Docs & Files | Files tab (add Shortcut to OneDrive for desktop access) | All of Box (add Box Drive for desktop access) | |

| Email Forwards | |||

| Card Table | Tasks by Planner and To Do | MeisterTask |

Managing Exported HTML Files

To be honest, having all our Basecamp created documents export as HTML files was challenging. In Box, the HTML files would just display the code view when opened online, and this was frustrating to our colleagues who use Box. While Teams would display the rendered web pages of the HTML files very well, any relative links between HTML files would be broken. For staff who wanted, essentially, a clone of their Basecamp project site, we directed them to use Box Drive or to sync a folder in their Team to OneDrive. When opened that way, the exported files would be navigable as normal, so we saw this as more of a challenge of guiding user behavior rather than manipulating the files themselves. Since we had encountered these issues in our preliminary testing of workflows and exports, we built that guidance into the first explanatory screencasts we made. Foregrounding those issues helped many people avoid them altogether.

Supporting Staff through the Transition

Overall, we had a very smooth transition for staff. In terms of time invested in this process, the Basecamp Migration Team spent a lot of time upfront preparing documentation and helpful how-to videos. We set up a centralized space for staff to find all of our documentation and to ask questions, and we also scheduled several blocks of open office hours to offer more personalized help. That work supported staff who were comfortable managing their own export, and the number of teams requiring administrator support or additional training ended up being manageable. The deadline for submitting requests for an administrator export was about one month before the cancellation date, but many teams submitted their requests earlier than that. All of these strategies worked well, and we felt very comfortable cancelling our account on the appointed day. We migrated out of Basecamp, and you can too!