Post contributed by Brooke Guthrie, Research Services Librarian.

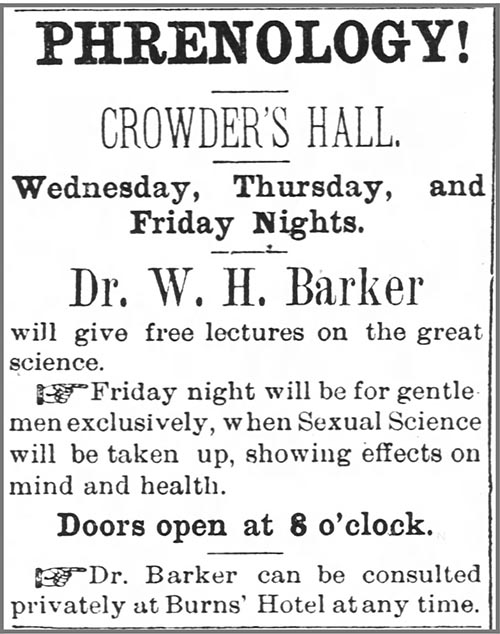

During the 1870s and 1880s, Dr. W. H. Barker traveled around North Carolina giving public lectures and, according to an 1873 article in The New Berne Times, “feeling the heads of the people.” This may seem strange, but Dr. Barker was no ordinary physician. He was a phrenologist and, as a phrenologist, touching heads was his specialty.

In the nineteenth century, the shape of a head was thought to reveal a lot about a person’s strengths and weaknesses. The size of various bumps or “organs” on your head could determine whether you, for instance, were combative, prone to secretiveness, or endowed with good digestive power. Phrenology began in Europe, but proved most popular in America. Phrenologists like Dr. Barker took advantage of the craze and began to offer professional readings to average people in small towns.

Phrenology was such an accepted “science” that practitioners were occasionally called as expert witnesses in court cases. Dr. Barker was subpoenaed in 1885 to testify at the murder trial of Ben Richardson. According to newspaper accounts, Dr. Barker was there “to determine Richardson’s insanity from a phrenological standpoint.” He also examined a state senator and concluded that the politician would do well in his job.

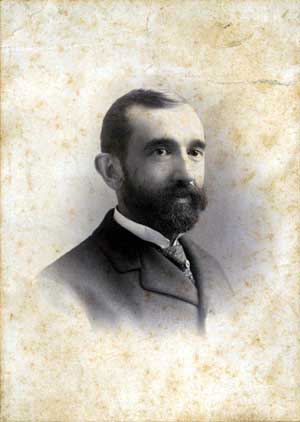

Dr. Barker was a respected practitioner. The Charlotte Observer stated in 1876 that Barker was “not a strolling humbug,” but rather a “gentleman of scientific attainment.” When Barker, a native of Carteret County, died in 1886, obituaries were published in several newspapers commenting on Barker’s wonderful skill and natural phrenological ability. Dr. Barker analyzed many heads during his career. Announcements for his lectures and head readings appear in newspapers across the state. Demand was so high that he often stayed in a town for weeks at a time speaking to large crowds and examining heads for several hours each night.

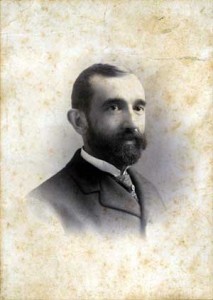

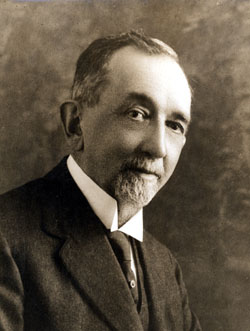

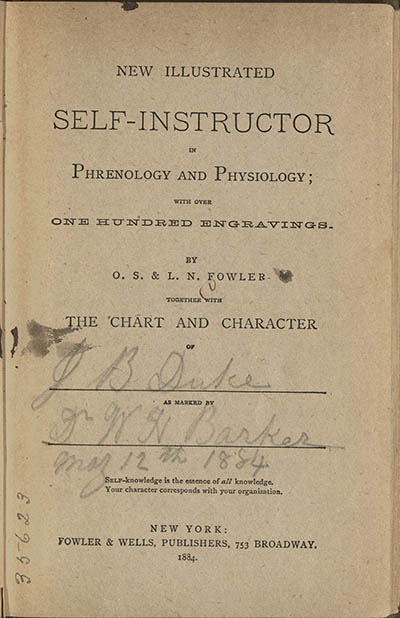

In May 1884, Barker analyzed a pair of rather famous heads: those belonging to Washington Duke and his youngest son, James Buchanan Duke. In the 1880s, the Duke family’s tobacco company was thriving. James B. Duke had turned the firm of W. Duke Sons & Co. toward the mass manufacture and mass marketing of cigarettes. Barker’s phrenology readings were taken the same year that W. Duke, Sons and Company opened a factory in New York and eight years before, with the financial help of the Dukes, Trinity College would move to Durham. Perhaps Washington, then in his mid-sixties, and his son, in his late twenties, saw a phrenology reading as a way to celebrate the family’s successes.

|

|

|

Dr. Barker recorded his assessment of the Dukes in New Illustrated Self-Instructor in Phrenology and Physiology. This small book, written by O. S. and L. N. Fowler, two of America’s foremost phrenologists, provides a chart for a personal phrenology exam along with a detailed explanation of how certain head “organs” correspond to certain traits. The Rubenstein Library has two copies of New Illustrated Self-Instructor, one for the analysis of each Duke.

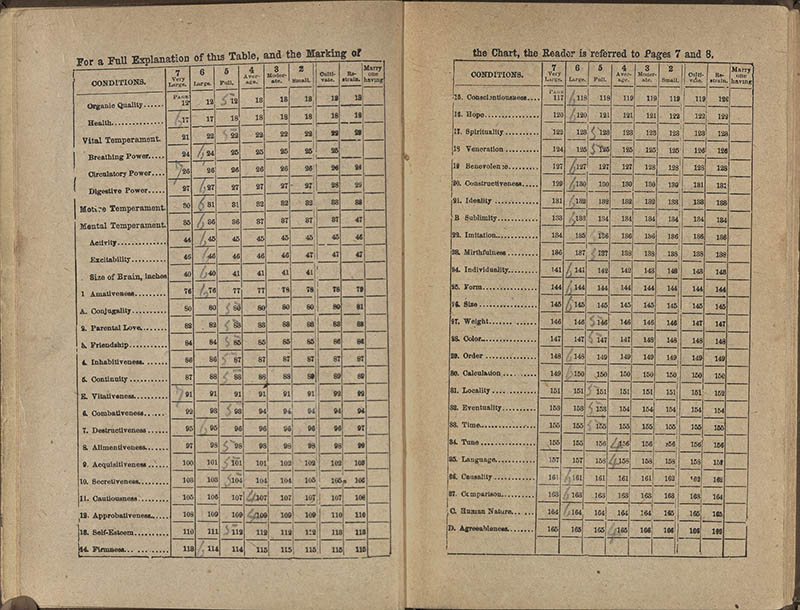

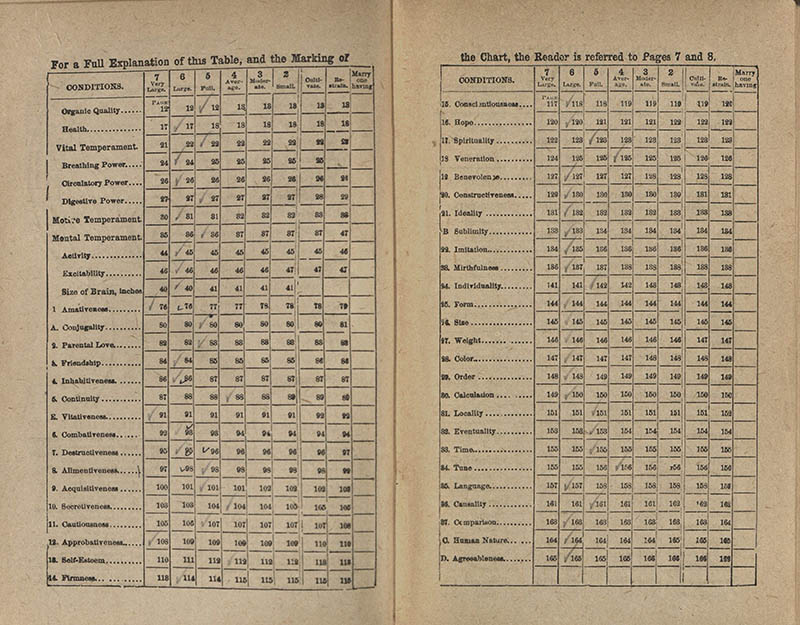

The next two images are charts from New Illustrated Self-Instructor showing the readings of Washington and James B. Duke. The far left column of the chart lists the “conditions” that can be measured with phrenology. The next six columns allow Dr. Barker, after feeling and measuring each Duke’s head, to note the size of the skull portion that corresponds to each condition. Washington Duke, for instance, was marked as having a “large” organ for firmness. (James B. Duke was also “large” in this area.)

The readings reveal quite a bit about the Dukes. Washington Duke is slightly less cautious than his son. The organ associated with vitativeness is very large in both men, indicating that they “shrink from death, and cling to life with desperation.” James B. Duke ranks higher in the condition of approbativeness, suggesting that the son is “over-fond of popularity” and ostentatious. Perhaps fittingly, approbativeness is described as the main organ of the aristocracy. Fortunately for Washington Duke, a man older than his son by several decades, he has higher circulatory and digestive power. Both rank as “full” in the parental love category indicating that they “love their own children well, yet not passionately.” One wonders what James B. Duke thought of this assessment of his father’s parenting skills.

The readings of both men are overwhelmingly positive. They are, apparently, below average in no way. It is certainly possible that both men were well-endowed in all qualities, but it also just as likely that Dr. Barker, a businessman himself, would want to flatter his wealthy clients. We can only guess at the response Dr. Barker would have received if he had concluded that the Duke men were weak and dull with low self-esteem.

After 1884, the Duke family continued to prosper. James B. Duke formed the American Tobacco Company in 1890 and the family soon entered the textile business. Duke-led companies would, by the early 1900s, control the national tobacco market and the Dukes would make an enormous fortune in a variety of industries. Washington Duke died in 1905 at the age of 84. In 1924, James Buchanan Duke established The Duke Endowment, with Trinity College as one of its main beneficiaries, and the school was renamed in honor of Washington Duke and his family.

While Duke University saw enormous growth in the twentieth century, critiques of phrenology appeared as early as the 1840s and its popularity waned in the following decades. Now considered a pseudoscience, phrenology is often associated with racist and sexist theories.