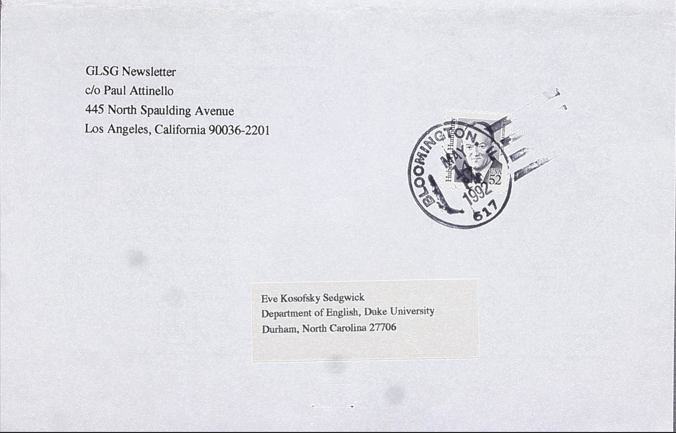

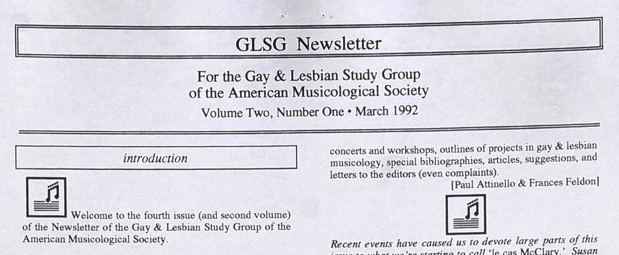

Contributed by David K. Seitz, associate professor of cultural geography, Harvey Mudd College: Recipient of an Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick Research Travel Grant, 2024-25, supported by the Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick Foundation

The intellectual and creative legacy of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick is so multi-layered and wide-ranging that even such adjectives scarcely do it justice. But across the many webs and folds of experience and knowledge that Sedgwick’s work interweaves, it is difficult to miss the recurrence of a particular charismatic megafauna: the giant panda.

Pandas, art historian Jason Edwards observes, were “were crucial to Sedgwick’s late style,” appearing in several of her books, poems, and craft works from 1996 onward. But Sedgwick’s panda-love, Edwards points out, began much earlier, as an attachment formed in childhood and sustained in the exchange of countless panda cards over the course of her remarkable marriage to optometry professor Hal Sedgwick. Eve Sedgwick noticed all kinds of queer possibilities and pleasures in pandas – their ambiguous gendering, cozy contentment, shyness, roundness – and in the cross-cultural encounters convened around them, as in China’s practice of “panda diplomacy.”

I came to the Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library under the auspices of the Sallie Bingham Center with a particular interest in Sedgwick’s attention to questions of race, class, and empire. Although I certainly imagined that such questions might come up in her correspondence with Richard Fung, the acclaimed Chinese-Trinidadian-Canadian queer experimental filmmaker, I had not anticipated the place of the panda in such exchanges.

In March 1991, Fung visited Duke under Sedgwick’s auspices, screening his 1990 film My Mother’s Place and lecturing on questions of race, gender, and sexuality in Chinese and Caribbean diasporas. There, he met Sedgwick’s student, José Esteban Muñoz, who would later analyze “My Mother’s Place” in his germinalbook Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Politics of Performance. Upon returning home to Toronto, Fung chose an apposite thank-you note for Eve Sedgwick’s hospitality: a pop-up card of two pandas in playful repose, sold to benefit the World Wildlife Fund.

The card must have delighted Eve, both in its imagery and in its three dimensionality, given her interest in the aesthetics of texture and touch. Fung’s postscript – “Which do you think is the girl panda and the boy panda? How do you know?” – subtly extended his longstanding, both serious and playful criticisms of Western stereotypes about Asian genders and sexualities, and must also have affected her. Two years later, in Tendencies, Sedgwick listed Fung among queer artists of color who “do a new kind of justice to the fractal intimacies of language, skin, migration, state.”

Fung’s panda card underscores the wisdom of Edwards’s advice against dismissing Sedgwick’s panda-love as “childish” or “peripheral” to her intellectual and creative contributions. If anything, the card offers an apt metaphor: it is the surprises that “pop up” in Sedgwick’s archive and in all archival encounters that often prove the most informative.

Further Reading:

Edwards, Jason, ed. Bathroom Songs: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick as a Poet, (Santa Barbara, California: Punctum Books, 10 Nov. 2017) doi: https://doi.org/10.21983/P3.0189.1.00.

Edwards, Jason. Queer and Bookish: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick as Book Artist, (Santa Barbara, California: Punctum Books, 03 Mar. 2022) doi: https://doi.org/10.53288/0328.1.00.

Fung, Richard, dir. My Mother’s Place (Toronto, Canada: V-Tape, 1990).

Hu, Jane. “Between us: A queer theorist’s devoted husband and enduring legacy.” The New Yorker, (9 Dec. 2015): https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/between-us-a-queer-theorists-devoted-husband-and-enduring-legacy.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Politics of Performance, (Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1 May 1999).

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. A Dialogue on Love, (Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press, 9 Jun. 2000).

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Tendencies, (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, Oct. 1993) doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822381860.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. The Weather in Proust, ed. Jonathan Goldberg, (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, Dec. 2011) doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822394921.

Given this context, it was newsworthy when Wilhelmina Reuben, a member of Duke’s first class of Black undergraduates, was

Given this context, it was newsworthy when Wilhelmina Reuben, a member of Duke’s first class of Black undergraduates, was