The Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library is pleased to announce the recipients of the 2025-2026 travel grants. Our research centers annually award travel grants to students, scholars, and independent researchers through a competitive application process. We extend a warm congratulations to this year’s awardees. We look forward to meeting and working with you!

The travel grants for the Archive of Documentary Arts and Human Rights Archive have been paused for the 2025-2026 cycle.

Doris Duke Archives

Joan Marie Johnson, Northwestern University, “Doris Duke and the Business of Philanthropy”

Richard Treut, “Doris Duke’s Stewardship of Duke Farms”

Elon Clark History of Medicine Travel Grants

Jessica Brabble, Ph.D. Candidate, College of Willilam & Mary, “Her Best Crop: Eugenics, Agricultural Programming, and Child Welfare, 1900-1964”

Michael Ortiz-Castro, Lecturer, Department of History, Bentley University, “Acts of Citizenship: Belonging and Biology in the Post-Reconstruction US.”

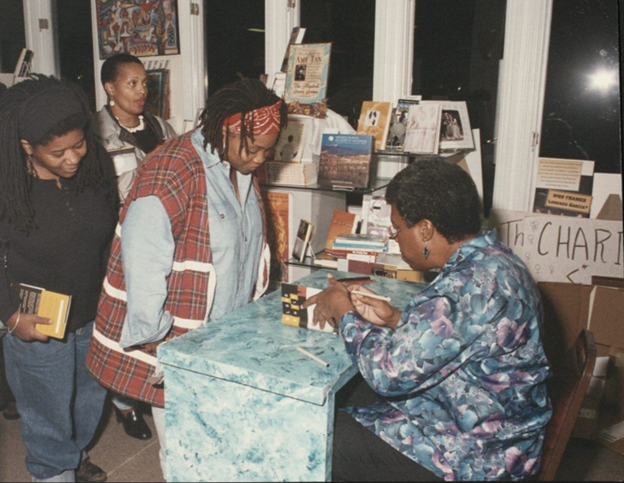

John Hope Franklin Research Center

Irene Ahn, Faculty, American University, “Bridging Divides through Local Reparations: Examining How Communities Repair Racial Injustices”

Emmanuel Awine, Ph.D. Candidate, Johns Hopkins University, “The Socio-Political History of the Raided Communities in Northern Ghana and Southern Burkina Faso 1800-2000”

Carlee Migliorisi, M.A. Candidate, Monmouth University, “Asbury Park Uprising: Race, Riots, and Revenue”

Maria Montalvo, Faculty, Emory University, “Imagining Freedom”

Michael Ortiz, Faculty, Bentley University, “Acts of Citizenship: Belonging and Biology in the Post Reconstruction US”

Summer Perritt, Ph.D. Candidate, Rice University, “A Southern Reclamation: Understanding Black Identity and Return Migration to the American South in the Post-Civil Rights Era, 1960-2020”

McKenzie Tor, Ph.D. Candidate, University of Missouri, “The Black Temperance Movement in Nineteenth Century America”

Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History

John Furr Fellowship for JWT Research

Raffaella Law, “Global Branding, Local Tastes: Nestle and the Rise of Internet-Age Food Advertising in the 1990s”

Joseph Semkiu, “Wartime Advertising and Radio Voices: Selling Masculinity On and Off the Radio to the 1940s US Home Front”

Alvin A. Achenbaum Travel Grants

James Bowie, “The 20th-Century Development of the Logo as a Cultural Object”

Bryce Evans, “Marketing Abundance: JWT’s Creative and Strategic Approach to the Pan Am Account”

Townsend Rowland, “Supplementation, Radiation, Mutation: Food and Scientific Authority in Postwar America”

Mark Slater, “Big Tobacco and Blackness: American Advertising, Black Culture, and Cigarettes in Post-WW2 America”

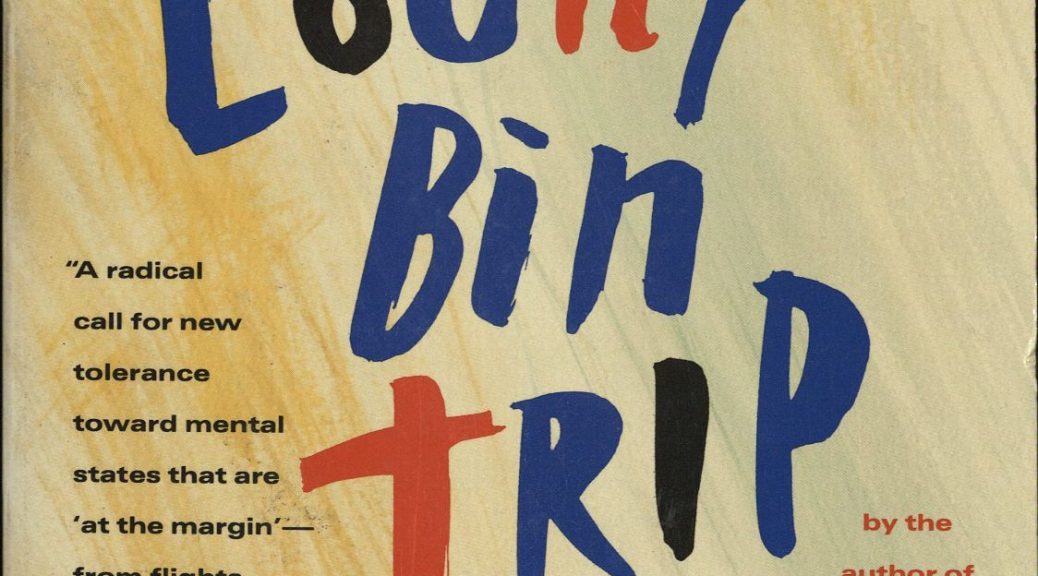

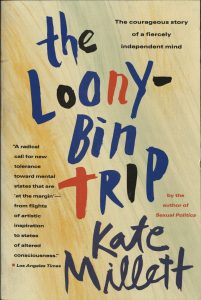

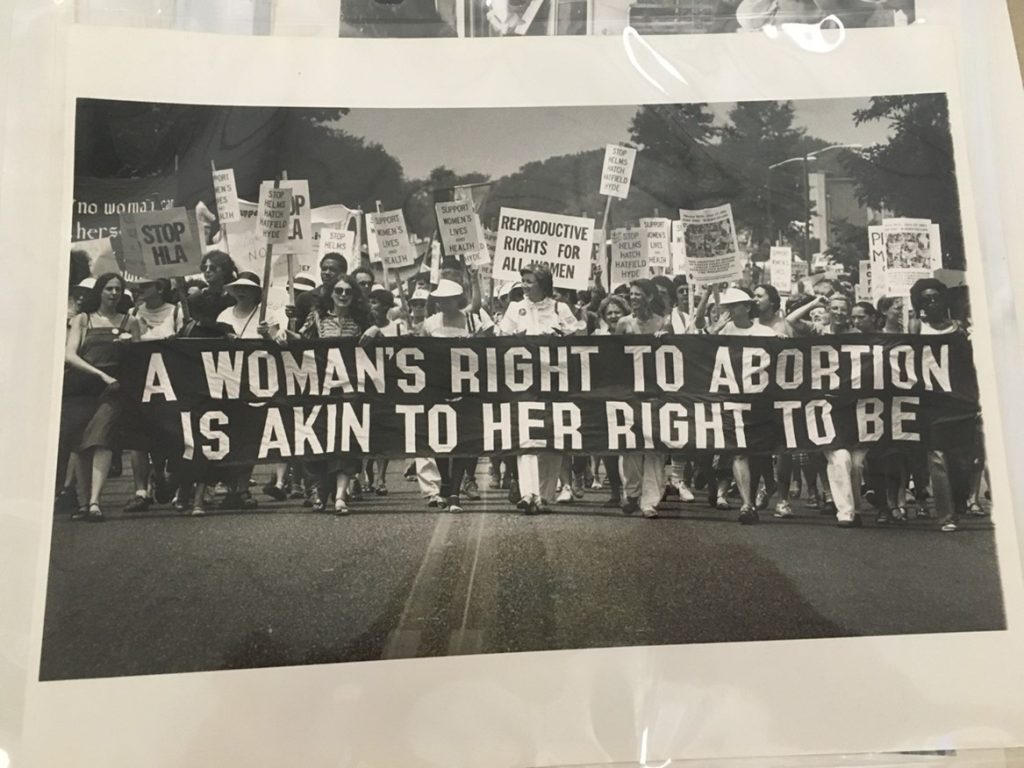

Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture Travel Grant Awardees

Mary Lily Travel Grant

Daniel Belasco, Independent Researcher, Al Held Foundation, “Total Revolution: The Origins of the Feminist Art Movement, 1963-1969”

Ayumi Ishii and Kate Copeland, Independent Researchers, Pacific Northwest College of Art, “Compleat and Infallible Recipes”

Chloe Kauffman, Graduate Student, University of Maryland, College Park, “’If women are curious, women also like to speak’: Unmarried Women, Sexual Knowledge, and Female Mentorship in the Eighteenth-Century Anglo-Atlantic”

Lucy Kelly, Graduate Student, University of Sussex, Sussex Center for American Studies, “’I want to fight the fight. I want my rightful place’: Queer Worldmaking in the American South, 1970-2000”

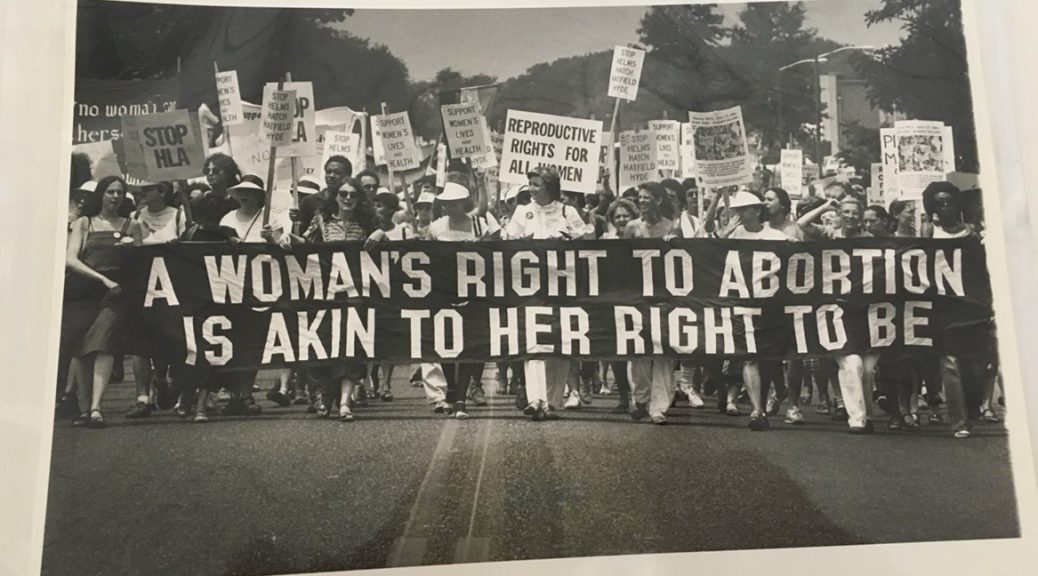

Lina-Marie Murillo, Faculty, University of Iowa, Gender, Women’s and Sexuality Studies, and History, “The Army of the Three and the Untold History of America’s Abortion Underground”

Melissa Thompson, Graduate Student, West Virginia University, “Redefining and Recreating the Meaning of Family, 1929 – 2010s”

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick Travel Grant

Stephanie Clare, Faculty, University of Washington, Seattle, “Eve’s Pandas: Queer Futurity and the More-Than-Human”

Julien Fischer, Postdoctoral Fellow and Lecturer, Stanford University, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, “Writing the Incurable: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick on Love and the Impossible”