This week was a very busy week in Conservation. We had the floors cleaned and sealed. “Easy enough,” you say? It literally took one week, a moving company, the flooring company, Facilities, Housekeeping, Facilities and Distribution Services, and of course a lot of work from Conservation staff.

Phase 1: Move half of all the things!

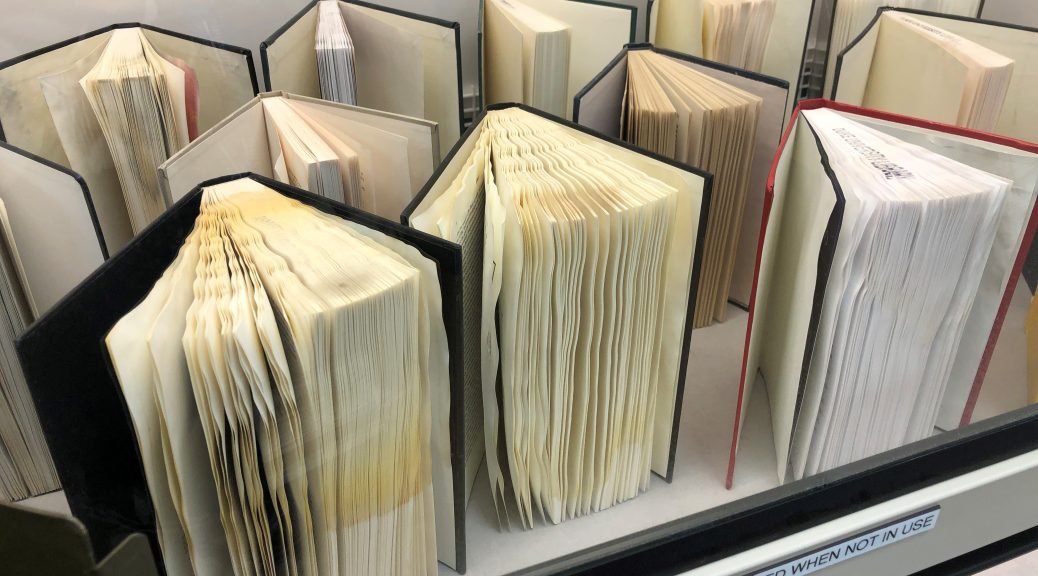

Before the equipment could be moved, lab staff had to shift all the books onto carts, label all the equipment and furniture, move sensitive equipment like the encapsulator, etc. Once that was done, the movers came and shifted half the lab to one end.

The fun part was uncovering the floors that have never seen light. This is what the cork looked like when it was installed in 2008!

Even with the light differences you can really see how the cleaning and sealing has improved the look of the floors. They feel so much better, too.

Phase 2: Move all the things to the other side of the room!

Once the first half of the cork floors were cleaned, all the furniture and equipment had to move to the opposite side of the room. We decided not to move heavy things like the two board shears and the flat files.

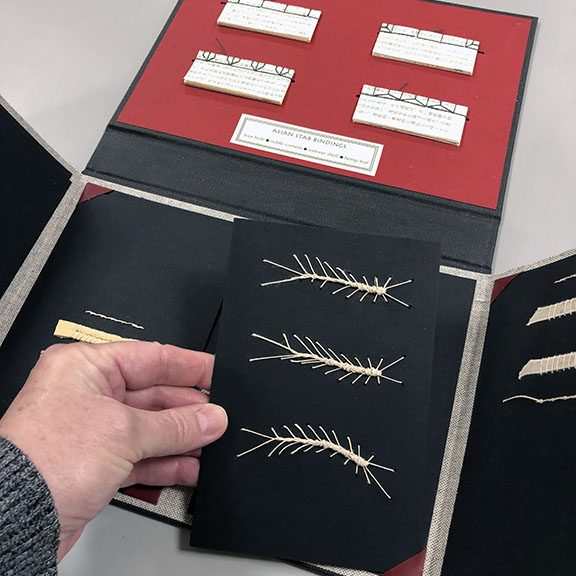

Mid-week we helped move some paintings. We also worked on several projects that were not located in the lab including some work for the Lilly renovation and helping in Technical Services with some boxing.

Phase 3: Move all the things back, then move some more things!

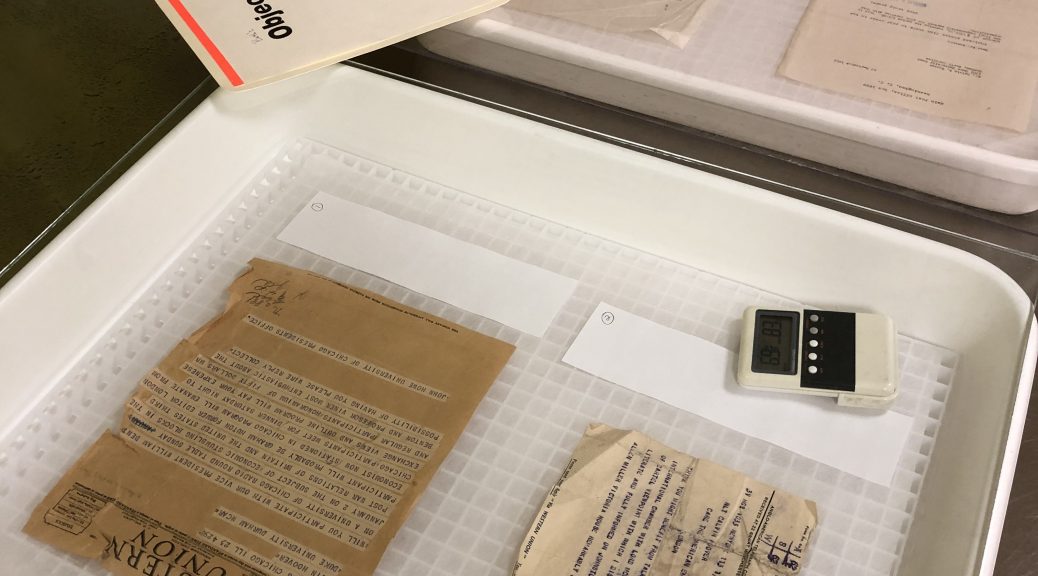

Lastly, the floors in the store room and photo documentation room got cleaned. To facilitate that work we moved what we could out of those rooms into the lab.

Those floors are now nicely cleaned thanks to Housekeeping. They have never looked this shiny even when they were new!

We are so happy to have this work done. We know it took a lot of coordination and time, and the disruption was real for all the departments involved. Thanks to everyone who helped make this happen!

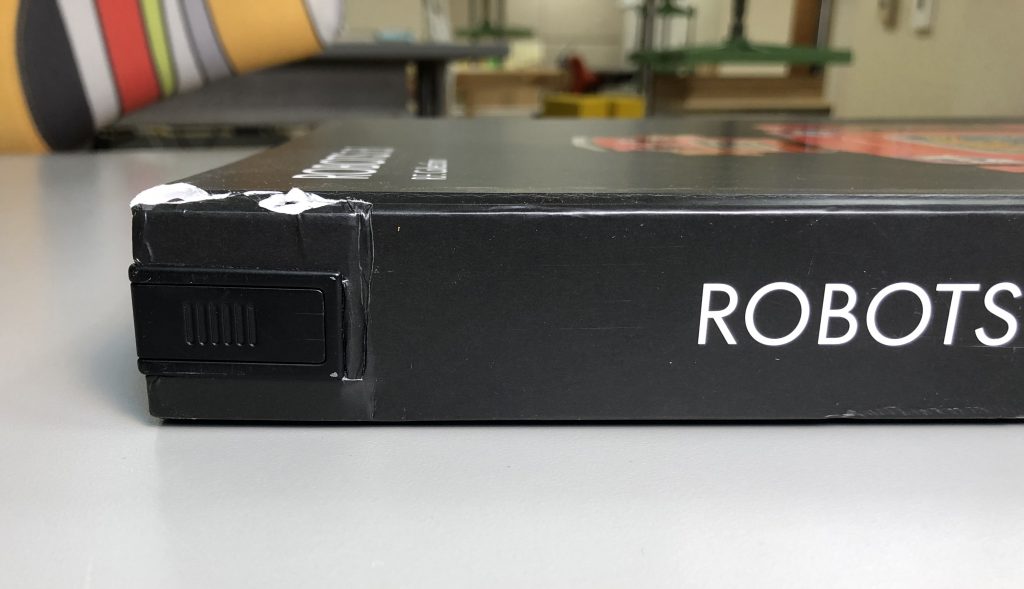

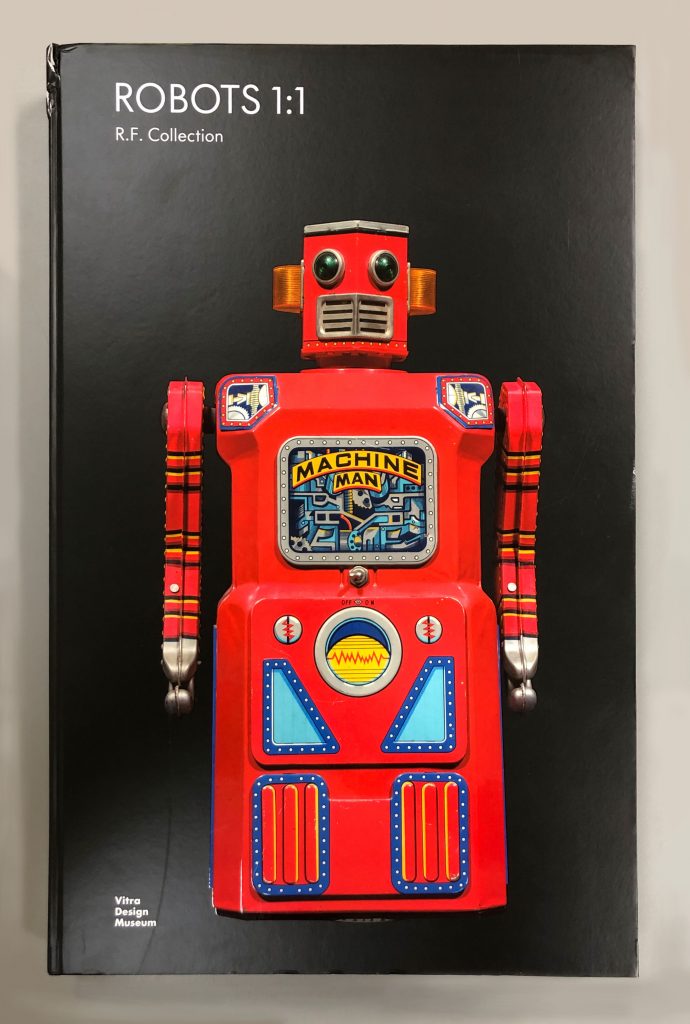

The unique feature of this book, however, is a USB memory stick that has been integrated into the headcap. The stick contains a film by Luka Dogan, showing a selection of the robots in action.

The unique feature of this book, however, is a USB memory stick that has been integrated into the headcap. The stick contains a film by Luka Dogan, showing a selection of the robots in action.