This month on the 1091 Project we highlight those materials that come to the lab that some would say are explicit or offensive and shouldn’t be in a library, but in the context of our collections they are important materials that deserve the same attention as any other. These materials cross multiple academic themes including political science, art and art history, religion, social science, etc. I am a firm believer in collecting these things because they are an important window into our culture and society. Yet if a VIP tour is coming through the lab, I don’t necessarily want to have them out on the bench.

This month on the 1091 Project we highlight those materials that come to the lab that some would say are explicit or offensive and shouldn’t be in a library, but in the context of our collections they are important materials that deserve the same attention as any other. These materials cross multiple academic themes including political science, art and art history, religion, social science, etc. I am a firm believer in collecting these things because they are an important window into our culture and society. Yet if a VIP tour is coming through the lab, I don’t necessarily want to have them out on the bench.

Some materials in the Human Rights Archives fit this description because those fighting against human rights often use hate speech and violence to express their viewpoint. We recently worked on a collection of materials from a deceased member of a certain fraternal hate organization. This collection included his membership card and several group photographs from conventions of the membership. These pictures are not dissimilar from what a group picture taken at a library convention looks like, except of course for the clothing they are wearing, which is rather distinctive. These materials are unsettling to me not in content per se but in the their ordinariness.

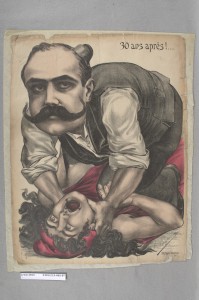

Last month Grace worked on preparing the Musee de Horreurs for digitization and exhibit. This collection of political caricatures was published in 1889-1900 in response to the Dreyfus Affair. While many of these materials are disturbing to see, they contain information that, in the context of the collection, sheds light on many aspects of French society at the turn of the 20th century. As objects they are beautifully rendered and printed, as social commentary they are incredibly effective albeit quite offensive.

For the past few months we have been making enclosures for the Sallie Bingham Center’s Drewey Wayne Gunn and Jacques Murat Collection of Gay American Pulps. These materials date primarily from the 1970’s and were printed on low quality paper with very cheaply produced paperback bindings. The content, though sexually graphic, makes sense in the context of the Bingham Center’s collection and is very valuable to researchers. We are not boxing these materials because of what they are but because, like any other brittle paperback, they need enclosures to keep them protected on the shelf and during transportation.

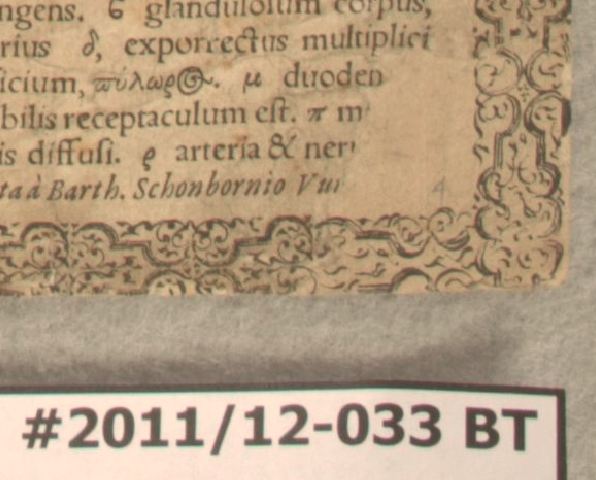

HOM provides us with a lot of extraordinarily graphic material that is also historic and very educational on many levels. I think my favorite items that have been in the lab recently are the medical flap books. Erin worked on these to get them ready for exhibit, and her treatments generated what we like to call, “the best before treatment image ever.”

Context is everything but we can still have a sense of humor about the collections we encounter! Let’s see what materials Parks Library Preservation is working on that are similar to these.