Today we will take a detailed look at how the Duke Chronicle, the university’s beloved newspaper for over 100 years, is digitized. Since our scope of digitization spans nine decades (1905-1989), it is an ongoing project the Digital Production Center (DPC), part of Digital Projects and Production Services (DPPS) and Duke University Libraries’ Digital Collections Program, has been chipping away at. Scanning and digitizing may seem straightforward to many – place an item on a scanner and press scan, for goodness sake! – but we at the DPC want to shed light on our own processes to give you a sense of what we do behind the scenes. It seems like an easy-peasy process of scanning and uploading images online, but there is much more that goes into it than that. Digitizing a large collection of newspapers is not always a fun-filled endeavor, and the physical act of scanning thousands of news pages is done by many dedicated (and patient!) student workers, staff members, and me, the King Intern for Digital Collections.

Pre-Scanning Procedures

Many steps in the digitization process do not actually occur in the DPC, but among other teams or departments within the library. Though I focus mainly on the DPC’s responsibilities, I will briefly explain the steps others perform in this digital projects tango…or maybe it’s a waltz?

Each proposed project must first be approved by the Advisory Council for Digital Collections (ACDC), a team that reviews each project for its strategic value. Then it is passed on to the Digital Collections Implementation Team (DCIT) to perform a feasibility study that examines the project’s strengths and weaknesses (see Thomas Crichlow’s post for an overview of these teams). The DCIT then helps guide the project to fruition. After clearing these hoops back in 2013, the Duke Chronicle project started its journey toward digital glory.

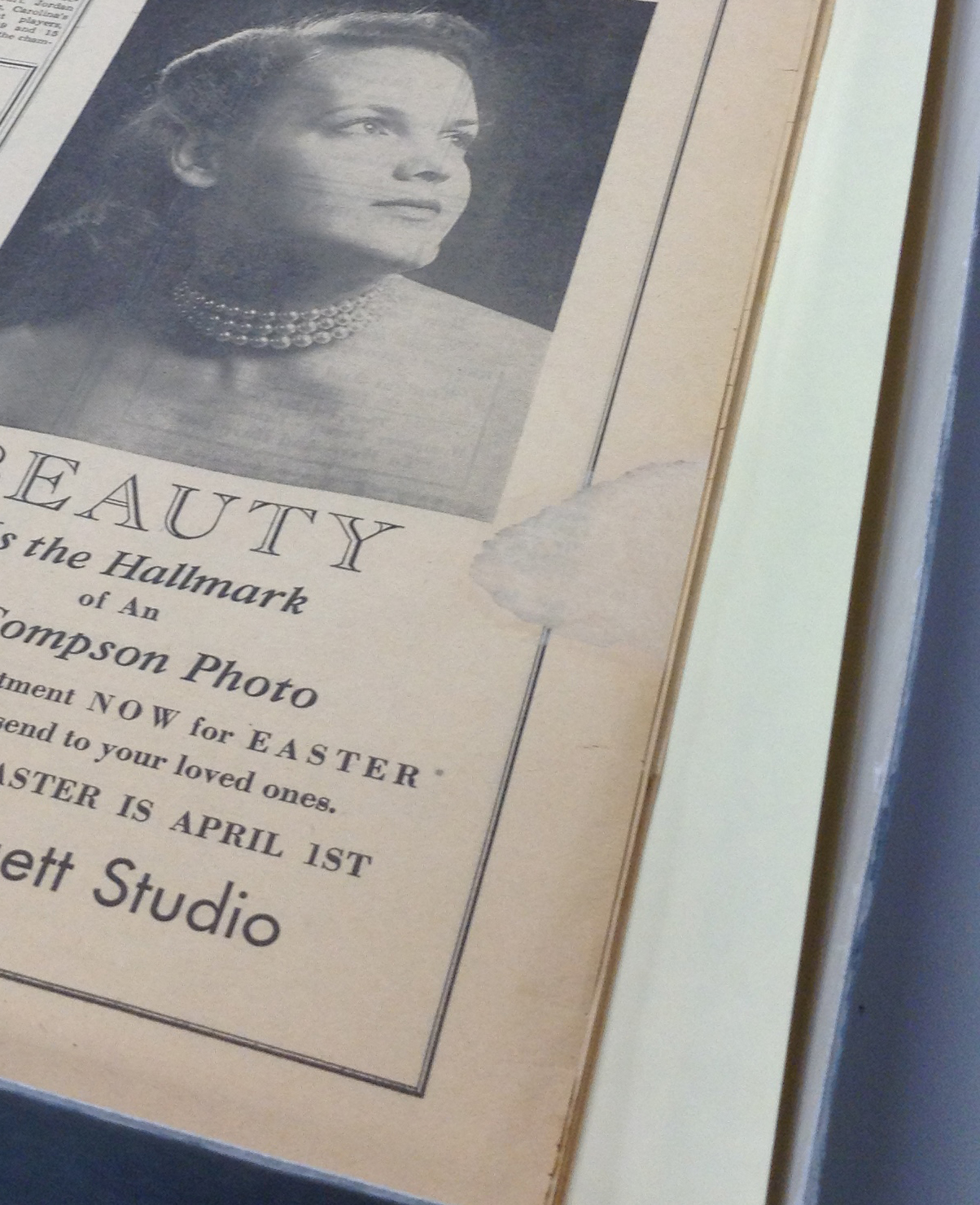

We pull 10 years’ worth of newspapers at a time from the University Archives in Rubenstein Library. Only one decade at a time is processed to make the 80+ years of Chronicle publications more manageable. The first stop is Conservation. To make sure the materials are stable enough to withstand digitizing, Conservation must inspect the condition of the paper prior to giving the DPC the go-ahead. Because newspapers since the mid-19th century were printed on cheap and very acidic wood pulp paper, the pages can become brittle over time and may warrant extensive repairs. Senior Conservator, Erin Hammeke, has done great work mending tears and brittle edges of many Chronicle pages since the start of this project. As we embark on digitizing the older decades, from the 1940s and earlier, Erin’s expertise will be indispensable. We rely on her not only to repair brittle pages but to guide the DPC’s strategy when deciding the best and safest way to digitize such fragile materials. Also, several volumes of the Chronicle have been bound, and to gain the best digital image scan these must be removed from their binding. Erin to the rescue!

Now that Conservation has assessed the condition and given the DPC the green light, preliminary prep work must still be done before the scanner comes into play. A digitization guide is created in Microsoft Excel to list each Chronicle issue along with its descriptive metadata (more information about this process can be found in my metadata blog post). This spreadsheet acts as a guide in the digitization process (hence its name, digitization guide!) to keep track of each analog newspaper issue and, once scanned, its corresponding digital image. In this process, each Chronicle issue is inspected to collect the necessary metadata. At this time, a unique identifier is assigned to every issue based on the DPC’s naming conventions. This identifier stays with each item for the duration of its digital life and allows for easy identification of one among thousands of Chronicle issues. At the completion of the digitization guide, the Chronicle is now ready for the scanner.

The Scanning Process

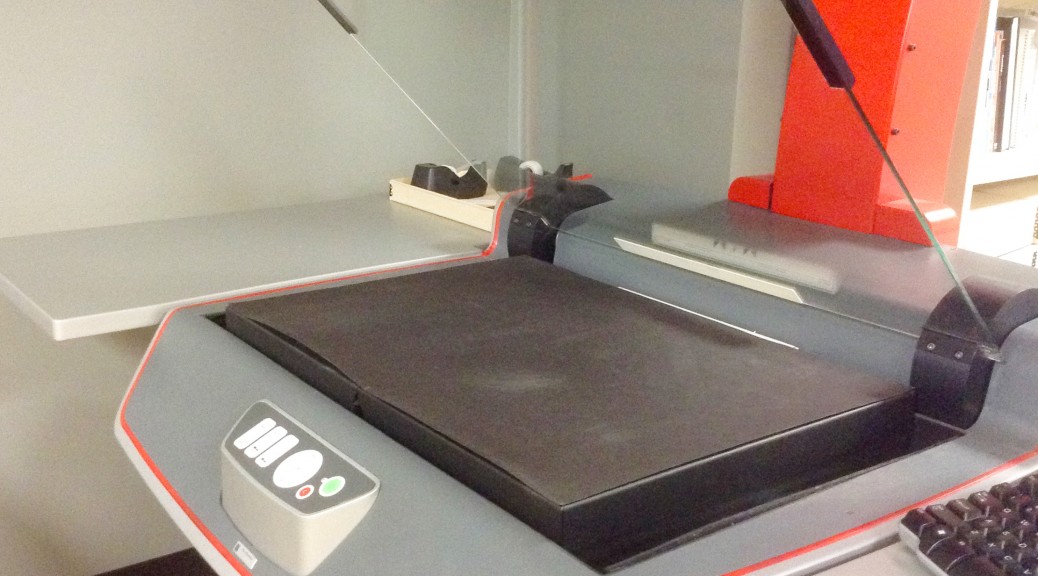

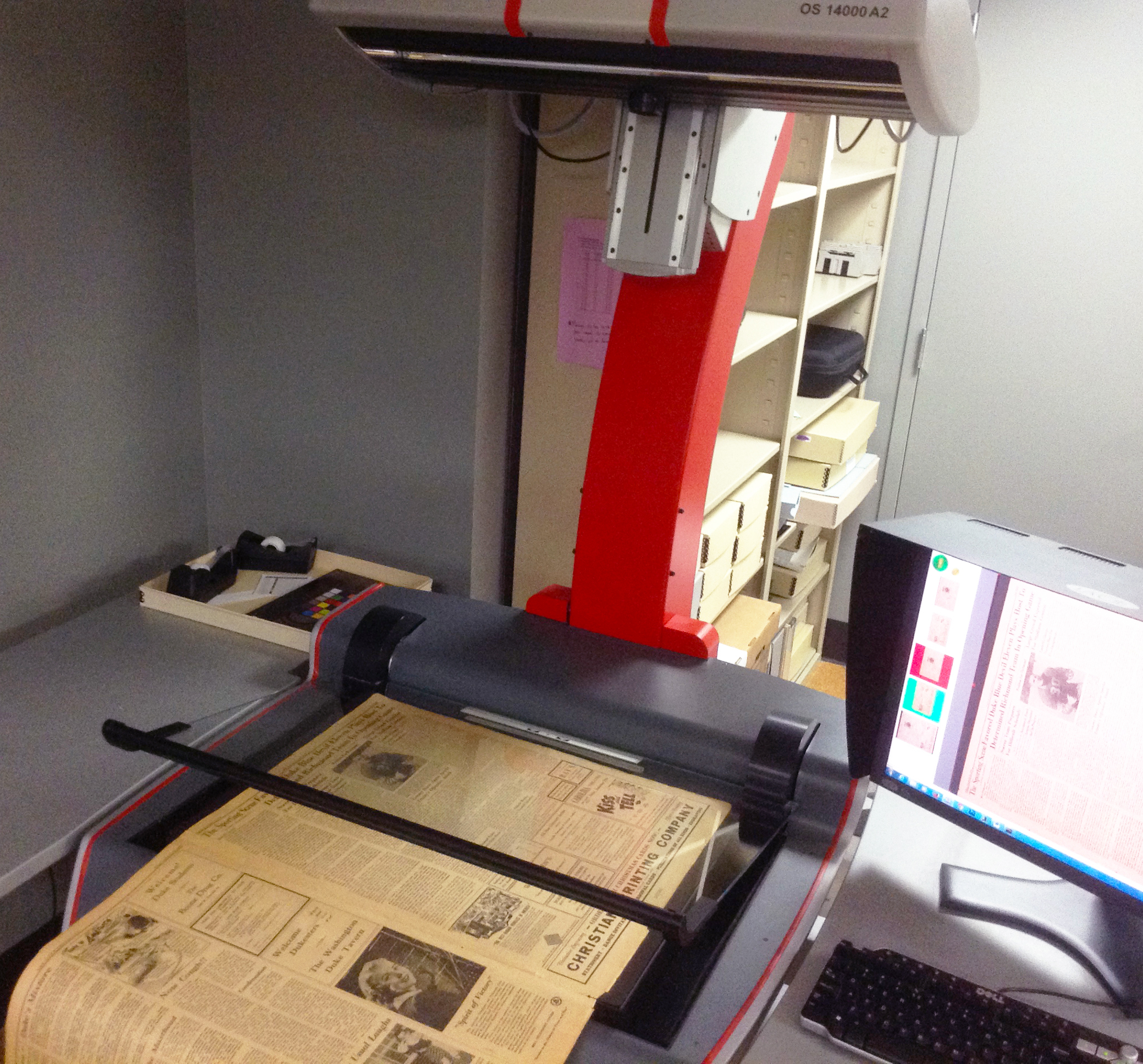

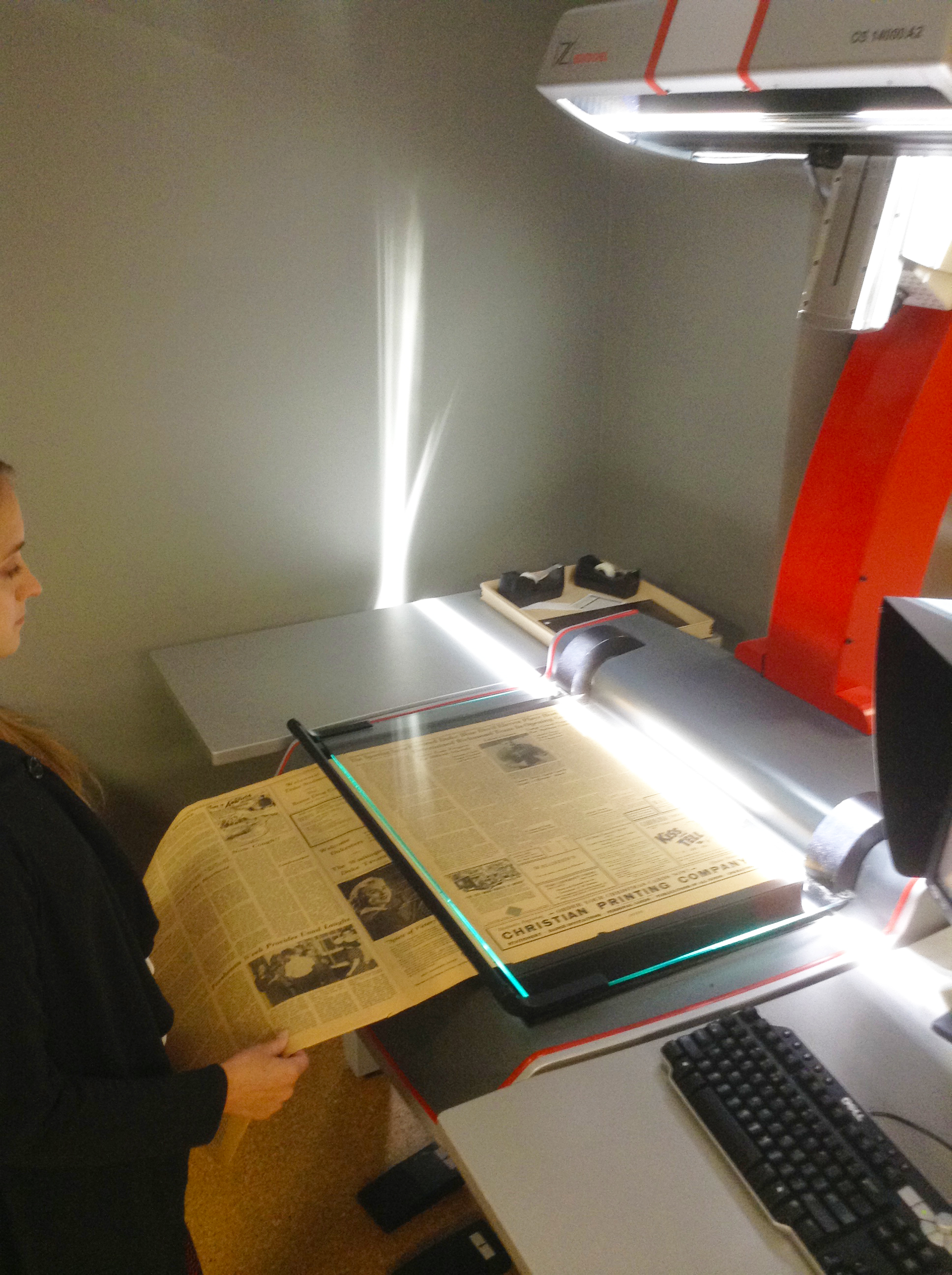

With all loose unbound issues, the Zeutschel is our go-to scanner because it allows for large format items to be imaged on a flat surface. This is less invasive and less damaging to the pages, and is quicker than other scanning methods. The Zeutschel can handle items up to 25 x 18 inches, which accommodates the larger sized formats of the Chronicle used in the 1940s and 1950s. If bound issues must be digitized, due to the absence of a loose copy or the inability to safely dis-bound a volume, the Phase One digital camera system is used as it can better capture large bound pages that may not necessarily lay flat.

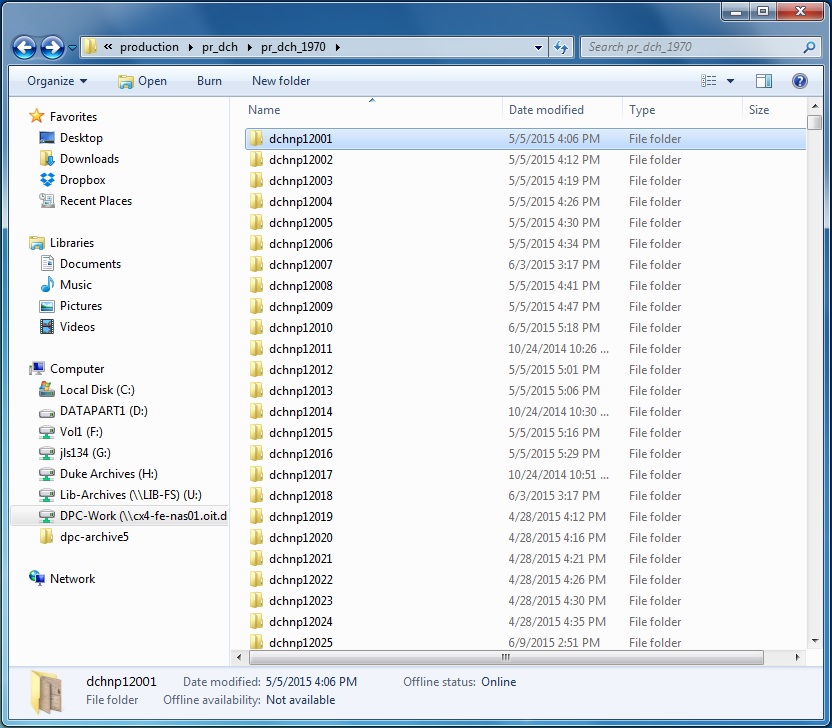

For every scanning session, we need the digitization guide handy as it tells what to name the image files using the previously assigned unique identifier. Each issue of the newspaper is scanned as a separate folder of images, with one image representing one page of the newspaper. This system of organization allows for each issue to become its own compound object – multiple files bound together with an XML structure – once published to the website. The Zeutschel’s scanning software helps organize these image files into properly named folders. Of course, no digitization session would be complete without the initial target scan that checks for color calibration (See Mike Adamo’s post for a color calibration crash course).

The scanner’s plate glass can now be raised with the push of a button (or the tap of a foot pedal) and the Chronicle issue is placed on the flatbed. Lowering the plate glass down, the pages are flattened for a better scan result. Now comes the excitement… we can finally press SCAN. For each page, the plate glass is raised, lowered, and the scan button is pressed. Chronicle issues can have anywhere from 2 to 30 or more pages, so you can image this process can become monotonous – or even mesmerizing – at times. Luckily, with the smaller format decades, like the 1970s and 1980s, the inner pages can be scanned two at a time and the Zeutschel software separates them into two images, which cuts down on the scan time. As for the larger formats, the pages are so big you can only fit one on the flatbed. That means each page is a separate scan, but older years tended to publish less issues, so it’s a trade-off. To put the volume of this work into perspective, the 1,408 issues of the 1980s Chronicle took 28,089 scans to complete, while the 1950s Chronicle of about 482 issues took around 3,700 scans to complete.

Every scanned image that pops up on the screen is also checked for alignment and cropping errors that may require a re-scan. Once all the pages in an issue are digitized and checked for errors, clicking the software’s Finalize button will compile the images in the designated folder. We now return to our digitization guide to enter in metadata pertaining to the scanning of that issue, including capture person, capture date, capture device, and what target image relates to this session (subsequent issues do not need a new target scanned, as long as the scanning takes place in the same session).

Now, with the next issue, rinse and repeat: set the software settings and name the folder, scan the issue, finalize, and fill out the digitization guide. You get the gist.

Post-Scanning Procedures

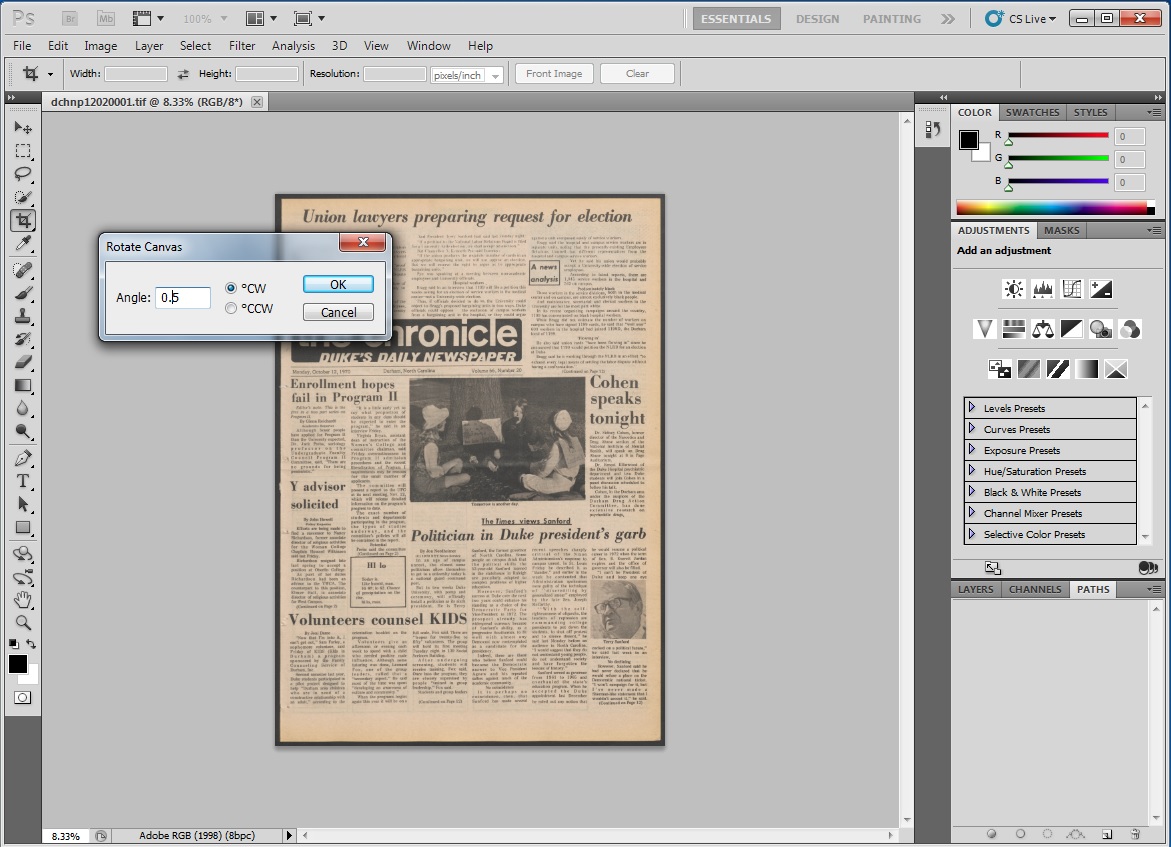

We now find ourselves with a slue of folders filled with digitized Chronicle images. The next phase of the process is quality control (QC). Once every issue from the decade is scanned, the first round of QC checks all images for excess borders to be cropped, crooked images to be squared, and any other minute discrepancy that may have resulted from the scanning process. This could be missing images, pages out of order, or even images scanned upside down. This stage of QC is often performed by student workers who diligently inspect image after image using Adobe Photoshop. The second round of QC is performed by our Digital Production Specialist Zeke Graves who gives every item a final pass.

At this stage, derivatives of the original preservation-quality images are created. The originals are archived in dark storage, while the smaller-sized derivatives are used in the CONTENTdm ingest process. CONTENTdm is the digital collection management software we use that collates the digital images with their appropriate descriptive metadata from our digitization guide, and creates one compound object for each Chronicle issue. It also generates the layer of Optical Character Recognition (OCR) data that makes the Chronicle text searchable, and provides an online interface for users to discover the collection once published on the website. The images and metadata are ingested into CONTENTdm’s Project Client in small batches (1 to 3 years of Chronicle issues) to reduce the chance of upload errors. Once ingested into CONTENTdm, the items are then spot-checked to make sure the metadata paired up with the correct image. During this step, other metadata is added that is specific to CONTENTdm fields, including the ingest person’s initials. Then, another ingest must run to push the files and data from the Project Client to the CONTENTdm server. A third step after this ingest finishes is to approve the items in the CONTENTdm administrative interface. This gives the go-ahead to publish the material online.

Hold on, we aren’t done yet. The project is now passed along to our developers in DPPS who must add this material to our digital collections platform for online discovery and access (they are currently developing Tripod3 to replace the previous Tripod2 platform, which is more eloquently described in Will Sexton’s post back in April). Not only does this improve discoverability, but it makes all of the library’s digital collections look more uniform in their online presentation.

Then, FINALLY, the collection goes live on the web. Now, just repeat the process for every decade of the Duke Chronicle, and you can see how this can become a rather time-heavy and laborious process. A labor of love, that is.

I could have narrowly stuck with describing to you the scanning process and the wonders of the Zeutschel, but I felt that I’d be shortchanging you. Active scanning is only a part of the whole digitization process which warrants a much broader narrative than just “push scan.” Along this journey to digitize the Duke Chronicle, we’ve collectively learned many things. The quirks and trials of each decade inform our process for the next, giving us the chance to improve along the way (to learn how we reflect upon each digital project after completion, go to Molly Bragg’s blog post on post-mortem reports).

If your curiosity is piqued as to how the Duke Chronicle looks online, the Fall 1959-Spring 1970 and January 1980-February 1989 issues are already available to view in our digital collections. The 1970s Chronicle is the next decade slated for publication, followed by the 1950s. Though this isn’t a comprehensive detailed account of the digitization process, I hope it provides you with a clearer picture of how we bring a collection, like the Duke Chronicle, into digital existence.