The Hartman Center and the Rubenstein Library are pleased to announce the arrival of the records of Hammacher Schlemmer, the 177-year-old hardware merchants-turned-purveyors of unique, odd, and oddly practical items, sold through a variety of catalogs that themselves represent one of the historical high points of creativity in catalog design and direct-to-consumer merchandising. The company produced its first catalog in 1881 and is considered the oldest catalog-based retail company in the United States, pre-dating Sears and Montgomery Ward by several years.

Hammacher Schlemmer began as a supplier of tools and trade equipment in 1848 in the Bowery section of New York by Charles Tollner. In 1853 he hired a 12-year-old German immigrant, William Schlemmer, as an assistant. A few years later another German immigrant, Albert Hammacher, invested in the growing hardware store. Eventually Schlemmer bought Tollner’s stake in the company, and in 1883 the company was renamed Hammacher Schlemmer & Co., a name it maintained for a century and a half.

Originally Hammacher Schlemmer sold primarily tools, from files and saws to more complicated machinery like the Lougee hair picker (a cotton gin-like machine for combing horsehair used in upholstery stuffing). By the 1900s the company had expanded to offer specialized tools for automotive, piano-building, and other trades; in the 1930s the company began to transition from hardware to housewares and general retail merchandise.

Originally Hammacher Schlemmer sold primarily tools, from files and saws to more complicated machinery like the Lougee hair picker (a cotton gin-like machine for combing horsehair used in upholstery stuffing). By the 1900s the company had expanded to offer specialized tools for automotive, piano-building, and other trades; in the 1930s the company began to transition from hardware to housewares and general retail merchandise.

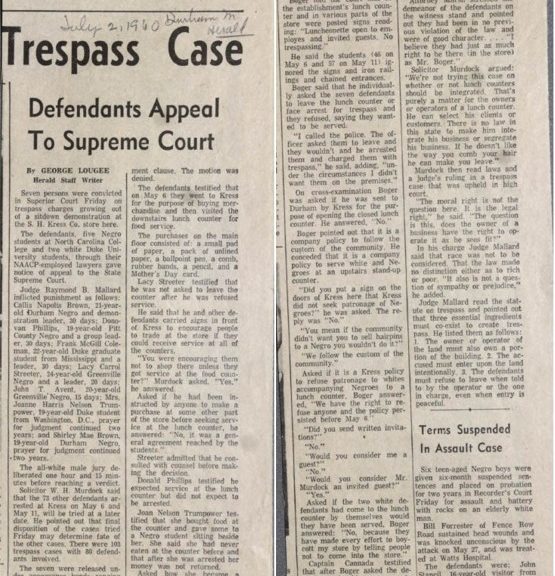

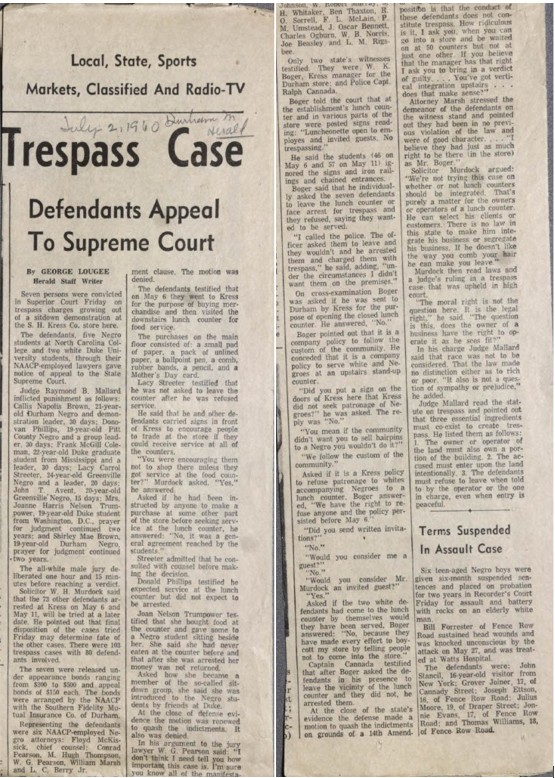

Hammacher Schlemmer maintained a store in the Bowery (and later branched to Chicago and Los Angeles), but an increasing percentage of sales came from its catalog operation. In the early days the catalogs doubled as selling aids for sales agents. They developed a reputation for detailed, useful print and finely rendered line drawings, as seen in this catalog entry for the Lougee hair picker:

With the transition to household goods (kitchen gadgets, furniture, cleaning implements and the like; a separate catalog for gourmet food products began in the 1930s) the catalog layouts shifted from line drawings to black-and-white (and later, color) photography. The catalogs for the centennial years 1947-1948 featured whimsical pastel drawings in color. By 1977 the catalogs would shift to an all-color layout.

The hardware line was dropped in the mid-1950s, and Hammacher Schlemmer turned to feature more high-end luxury goods, curated from other manufacturers’ items, as well as those developed by its own subsidiary, Invento, which was established in 1962. In 1983, the company established another subsidiary, Hammacher Schlemmer Institute, that focused on product testing and comparisons among competing products (similar to testing performed by groups such as Consumer Reports), later adding a Consumer Testing Panel for end-user testing and evaluation. In 1986, Hammacher Schlemmer began online sales in addition to its mail-order catalog operation. It joined SkyMall in 1991 as a charter member, advertising its products to airline passengers on U.S. domestic and selected international routes.

The catalogs featured a wild variety of products at every price point: slipper socks ($34.95); a walking stick with a built-in telescope ($89.95); a single-serving coffee maker ($199.95); a bamboo Tiki bar ($499.95); a leather chair in the shape of a baseball glove ($6,200); a full-scale working replica of the original 1966 Batmobile ($200,000); and a two-person fully functional electric submarine ($1.5 million). These products lived side-by-side in the page layouts of the catalog, a million-dollar submersible or a $65,000 robot next to entries for compression socks, garden hoses, and pens.

Along the way, Hammacher Schlemmer was instrumental in introducing a number of household items that started out as novelties and moved into mainstream popularity: pop-up toasters (1931); electric shavers (1934); steam irons (1948); telephone answering machines (1968); Mr. Coffee (1973); and the Cuisinart (1977), to name a few. Hammacher Schlemmer’s status as an American cultural icon is evidenced through parodies of the company’s catalog offerings that appeared in places such as the pages of Readers Digest and on the Family Guy television cartoon.

The Hammacher Schlemmer records should be available for researchers in the Rubenstein Library by late 2025. The collection offers a rich resource for scholars interested in topics as varied as advertising history; direct marketing; catalog design; line art; and the evolution of a historically important American retail establishment.