The Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library is pleased to announce the recipients of the 2024-2025 travel grants. Our research centers annually award travel grants to students, scholars, and independent researchers through a competitive application process. We extend a warm congratulations to this year’s awardees. We look forward to meeting and working with you!

Archive of Documentary Arts

Elizabeth Barahona, Ph.D. candidate, Northwestern University, “Black and Latino Coalition Building in Durham, North Carolina 1980-2010.” (Joint award with the Human Rights Archive)

Diana Ruiz, Faculty, University of Washington, Seattle, “Apprehension through Representation: Image Capture of the US-Mexico Border.” (Joint award with the Human Rights Archive)

Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture

Mary Lily Research Travel Grants

Taylor Doherty, Ph.D. candidate, University of Arizona, Department of Gender and Women’s Studies, “Minnie Bruce Pratt’s Anti-Imperialist Lesbian Feminist ‘Longed-for but Unrealized World.’”

Thalia Ertman, Ph.D. candidate, University of California, Los Angeles Department of History, “U.S. Feminist Anti-Nuclear Activism and Women’s Bodies, 1970s-1990s.”

Samuel Huber, Faculty, Yale University, Department of English. “A World We Can Bear: Kate Millett’s Life in Feminism.”

Alan Mitchell, Ph.D. candidate, Cambridge University, Faculty of Art History and Architecture, “Redefining Phoebe Anna Traquair through the lenses of historicism and intersectionality.”

Emily Nelms Chastain, Ph.D. candidate, Boston University, School of Theology, “The Clergywoman Question: The International Association of Women Preachers and Ecclesial Suffrage in American Methodism.”

Ana Parejo Vadillo, Faculty, School of Creative Arts, Cultures and Communications, Birkbeck, University of London, “Bound: The Queer Poetry of Michael Field.”

Carol Quirke, Faculty, American Studies, SUNY Old Westbury, “Feminism’s ‘Official Photographer:’ Bettye Lane, News Photography and Contemporary Feminism, 1969-2000.”

Paula Ramos, Independent Researcher, “Spatiality and gender: spatial circumstances of the creative process of feminist artists in the 1970s and 1980s.”

Dartricia Rollins, Graduate Student, University of Alabama, School of Library and Information Studies, “‘You Had to Be There:’ Charis’ 50-Year History as the South’s Oldest Independent Feminist Bookstore.”

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick Research Travel Grants

Ipek Sahinler, Ph.D. candidate, University of Texas Austin, “A Portrait of Young Women as Proto-Queer Thinkers: Eve Sedgwick vis-à-vis Gloria Anzaldúa.”

David Seitz, Faculty, Harvey Mudd College, “‘No Less Realistic’ but with ‘Different Ambitions’: Reparative Reading, Human Geography, and a Return to Sedgwick.

Doris Duke Foundation Travel Grants

Olivia Armandroff, Ph.D. candidate, University of Southern California, “Volcanic Matter: Land Formation and Artistic Creation.”

Cameron Bushnell, Faculty, Clemson University, Department of English. “‘The Invisible Orient’ in Orientalism Otherwise: Women Write the Orient.”

John Hope Franklin Center for African and African American History and Culture

Thomas Blakeslee, Ph.D. candidate, Harvard University, History Department, “Domestic Disturbances: The Resistant Masculinity of Black Fatherhood from Anti-Slavery to Civil Rights.”

Mara Curechian , Ph.D. candidate, School of English, University of St Andrews, “Acting Like Family: Performing Kinship in the Literature of the Civil War and Reconstruction.”

Michelle Decker, Faculty, Scripps College, English Department, George Washington Williams’s and Amanda B. Smith’s Appalachian Origins and African Explorations.”

Timothy Kumfer, Postdoctoral Fellow, Georgetown University, 2023-2024 Mellon Sawyer Seminar, “Counter-Capital: Grassroots Black Power and Urban Struggles in Washington, D.C.”

Hunter Moskowitz, Ph.D. candidate, Northeastern University, “Race and Labor in the Global Textile Industry: Lowell, Concord, and Monterrey in the Early 19th Century.”

Summer Sloane-Britt, Ph.D. candidate, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, “Visions of Liberation: Gender and Photography in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, 1960-1970.”

Mila Turner, Faculty, Clark Atlanta University, “Bridging Histories: Connecting the Atlanta Student Movement with College Student Activism throughout the Southeast”

Harry H. Harkins T’73 Travel Grants for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender History

Kadin Henningsen, Ph.D. candidate, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, “Walt’s Companions.”

Julie Kliegman, Author, book-length exploration of transgender pioneers.

John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History

John Furr Fellowship

Hannah Pivo, Ph.D. candidate, Columbia University, Department of Art History and Archaeology, “Charting the Future: Graphic Methods and Planning in the United States, c. 1910-60.”

Lewis Smith, Faculty, Brunel University London, Brunel Business School, Division of Marketing, “Marketing the State”: J. Walter Thompson Company and the Marketing of the Public Sector in Britain.”

Alvin Achenbaum Travel Grants

Warren Dennis, Ph.D. candidate, Boston University, “Hard Power Paths: Gender and American Energy Policy, 1960-2000.” (Joint award with History of Medicine with support from the Louis H. Roddis Endowment)

Dan Du, Faculty, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Department of History, “U.S. Tea Trade and Consumption after the American Revolution.”

Will Mari, Faculty, Louisiana State University, Manship School of Mass Communication, “Selling the computer to women media workers: gendered ads during the Cold War.”

Janine Rogers, Ph.D. candidate, University of California Los Angeles, Theater Department, “Performance, Militarization, and Materialisms: Canned Goods in Asian America”.

Foare

Jonathan MacDonald, Ph.D. candidate, Brown University, Department of American Studies, “Psychology Hits the Road: Driving Simulators, Billboards, and Hypnosis on the Highway.”

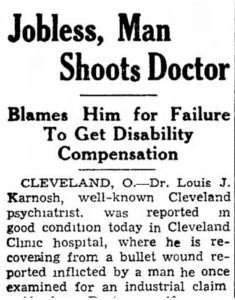

History of Medicine Collections

Warren Dennis, Ph.D. candidate, Boston University, “Hard Power Paths: Gender and American Energy Policy, 1960-2000.” (With support from the Louis H. Roddis Endowment; Joint award with the Hartman Center)

Ava Purkiss, Faculty, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Department of Women’s and Gender Studies, “After Anarcha: Black Women and Gynecological Medicine in the Twentieth Century.”

Baylee Staufenbiel, Ph.D. candidate, Florida State University, Department of History, “The Seven-Cell Uterus: De Spermate and the Anatomization of Cosmology.”

Brian Martin, Ph.D. candidate, University of Alabama, History Department, “Racial Theory and African American Medical Care in the U.S. Civil War.”

Human Rights Archive

Elizabeth Barahona, Ph.D. candidate, Northwestern University, “Black and Latino Coalition Building in Durham, North Carolina 1980-2010.” (Joint award with the Archive of Documentary Arts)

Diana Ruiz, Faculty, University of Washington, Seattle, “Apprehension through Representation: Image Capture of the US-Mexico Border.” (Joint award with the Archive of Documentary Arts)

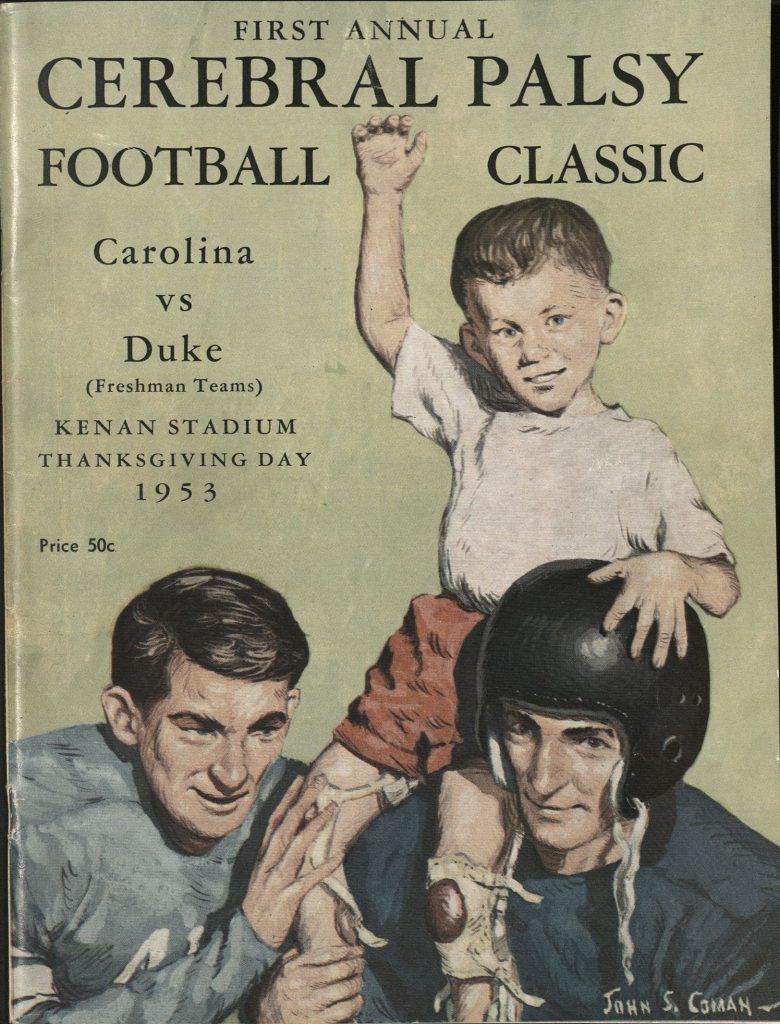

Kylie Smith, Faculty, Emory University. School of Nursing, Department of History, “No Place for Children: Disability, Civil Rights, and Juvenile Detention in North Carolina.”

Harrison Wick, Faculty, Indiana University of Pennsylvania (IUP) Special Collections and University Archives, “Examination of Primary Sources related to Social Justice and Latin American Immigration in the Human Rights Archive.”