Post contributed by Liz Adams, Rare Materials Cataloger

“I don’t know when I’ve ever been so flattered to see so many people getting up this early in the morning.”

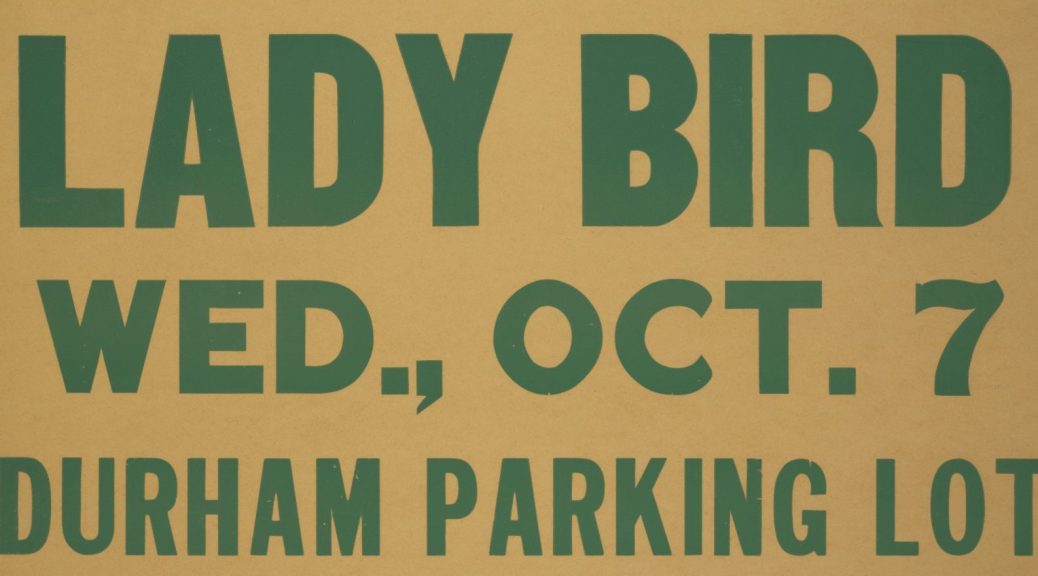

Lady Bird Johnson wasn’t exaggerating when she stumped for her husband’s presidential campaign in front of a crowd of 12,000 Durhamites on Wednesday, October 7th, 1964. It was 6:45 AM when a group of “early birds for Lady Bird” congregated to meet her at the Durham Parking Lot, brandishing free coffee and donuts. It was 7:04 AM when North Carolina politicians—including Terry Sanford (the governor and future president of Duke)—began their remarks. And it was 7:11 AM when the woman of the hour spoke behind Thalhimer’s department store in downtown Durham, highlighting the “present prosperity” of North Carolina, Lyndon B. Johnson’s familial connections to the state, and the Great Society he planned for the country.

To understand why Lady Bird Johnson stopped in Durham 56 years ago, we need to frame our story: It was 1964, and the Civil Rights Act (CRA) had just gone into effect on July 2nd. According to Hersch & Shinall (2014), the CRA “sought to improve access to voting, public accommodations, and employment as well as improve the overall status of individuals discriminated against on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, and national origin” (p. 425). At its heart, the CRA sought to create equalities where none existed, especially for Black Americans. It was and is an important, imperfect piece of legislation, one that only passed after years of tragedy and occasional triumph, including the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, the March on Washington, and the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Jr. Relying on an uneasy coalition of Republican and Democrat votes, Lyndon B. Johnson plowed the CRA through Congress. Southern Democrats and the Republican nominee for president, Barry Goldwater, stood in opposition (Hersch & Shinall, 2014).

Lady Bird Johnson believed in the CRA and her husband. Just as relevant to our story, she was also a native Texan and is quoted saying—in a piece for PBS NewsHour by Judy Woodruff—that she was “proud of the South” and “proud that [she was] part of the South” (2014). Lady Bird Johnson thus knew she needed to act. And so as Meredith Hindley documents in “Lady Bird Special,” on October 6th, she climbed aboard a train named the Lady Bird Special and embarked on a Whistle Stop Tour, a four-day trip winding through eight Southern states. Liaising with local politicians and their partners, she shored up support for the CRA, defended her husband’s past decisions, and fought for his future plans. In total, she gave 47 speeches and traveled over 1600 miles. Occasionally her path intersected with Lyndon B. Johnson’s campaign trail, but for the most part, she travelled alone or with her daughters. Finally, on October 9th, 1964, the Lady Bird Special arrived in New Orleans, La., and the President and First Lady of the United States reunited (Hindley, 2013).

28 days later, on Tuesday, November 3rd, 1964, Americans went to the polls. In a landslide victory, Lyndon B. Johnson won 44 states (and Washington, D.C.), 15 million more votes than Barry Goldwater, and 486 Electoral College votes (Levy, 2019). And although five of the six states he lost were in the South, there was a southern state he didn’t lose: North Carolina (Levy, 2019).

Interested in hearing Lady Bird Johnson’s speech in Durham? The Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library has made the audio recording available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7fyDOFkmGg8

Citations

Hersch, J., & Shinall, J. B. (2014). Fifty Years Later: The Legacy of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2523481

Hindley, M. (2013, May/June). Lady Bird Special. Humanities, the Magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities, 34(3). https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2013/mayjune/feature/lady-bird-special

Lady Bird’s Whistle Stop: Durham, NC: 10/7/64, 7:04 AM, Sound Recordings of Lady Bird Johnson’s Whistle Stop Campaign Tour, 10/6/1964-10/9/1965, Records of the White House Communications Agency, LBJ Presidential Library, viewed via YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7fyDOFkmGg8

Levy, M. (2019, October 27). United States presidential election of 1964. In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 6, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/event/United-States-presidential-election-of-1964

NewsHour, P. (2014, October 06). Remembering Lady Bird Johnson’s whistle-stop tour for civil rights. Retrieved October 06, 2020, from https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/remembering-lady-bird-johnsons-whistle-stop-tour-civil-rights