As Curator for the History of Medicine Collections in the Rubenstein Library, I often feel I have one of the best jobs in our library. I have the opportunity to work with wonderful people, but also remarkable rare books, manuscripts, and a wonderful collection of material objects.

Amputating saw

Over the years, a number of generous donors have given a variety of instruments and artifacts to the History of Medicine Collections. These items are often used in classroom instruction and teaching, and enrich and enliven exhibits and displays. The depth and breadth of this collection represents advances made in science and medicine, and reflect the importance of our historical understanding of material culture.

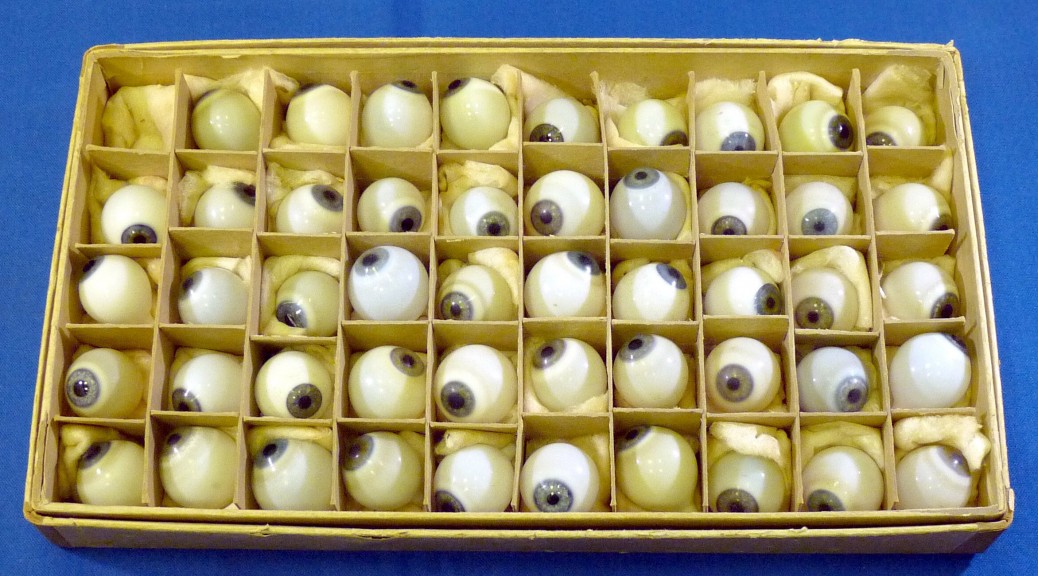

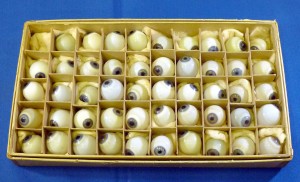

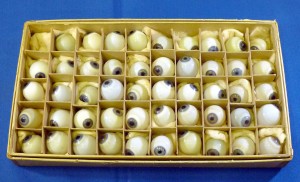

Glass eyeballs

Artifacts range in date from the 17th century to today, with many aspects of medicine highlighted in the collection: surgery, gynecology, pediatrics, and more. That “more” category includes items like our prosthetic glass eyeballs, the irises of which are all blue. These hand-blown glass items were intended to serve as prosthetic eyes. In a box reminiscent of a Whitman’s sampler, these eyes were made in a variety of sizes with differing tints of yellow and white. This box would have been used and carried by a traveling salesman of sorts – a person who visited doctors’ offices and sold them to patients in need.

A remarkable collection guide is now available to document the range of historical medical artifacts we have in our holdings.

Enema syringe

I’m often asked by students and researchers what my favorite item is. It really changes on a weekly basis. Currently, I’m intrigued by our range of microscopes. They are quite beautiful, span several centuries, and some include ivory specimen slides – with specimens!

Box mount microscope

Screw barrel microscope

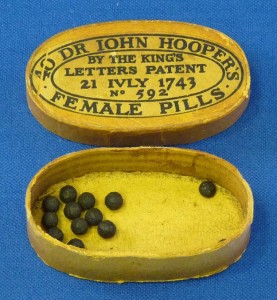

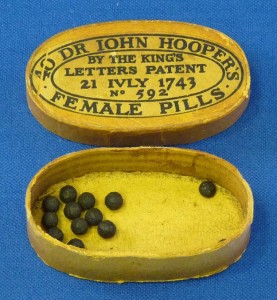

Some of my other favorites? Female pills and dental keys. Why were these female pills created and what are they? When I ask students, they often answer that it’s really just Midol.

Female pills

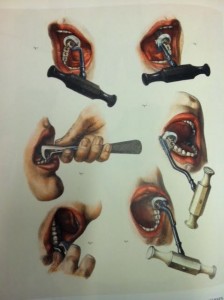

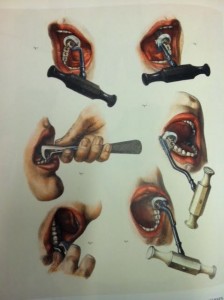

The dental keys really illustrate how medical technology has evolved in tooth extraction. The illustration below shows how a dental key would be used. This image is from the monumental work by J. M. Bourgery, Atlas of human anatomy and surgery, that includes a translation of his work and colored facsimiles. Of note, we also have the nine volume original work of Bourgery.

Dental key

A tremendous amount of thanks go out to so many people: our donors who have generously given such wonderful materials; previous staff of the History of Medicine Collections who researched these items, provided descriptions, and took photos that we can now share; and current staff from the Rubenstein Library’s technical services department and DUL digital projects – all who have made this guide possible.

What will your favorite item be?

Post by Rachel Ingold, Curator for the History of Medicine Collections in the Rubenstein Library.

![Maria Sibylla Merian. De europische insecten. Tot Amsterdam: by J.F. Bernard, [1730].](https://blogs.library.duke.edu/rubenstein/files/2016/01/merian.jpg)