Post contributed by Sagan Thacker, recent graduate of the University of North Carolina at Asheville BA in History. Read more in their senior thesis, “‘Something to Offend Everyone’: Situating Feminist Comics of the 1970s and ‘80s in the Second-Wave Feminist Movement,” forthcoming in the University of North Carolina at Asheville Journal of Undergraduate Research and available to read here.

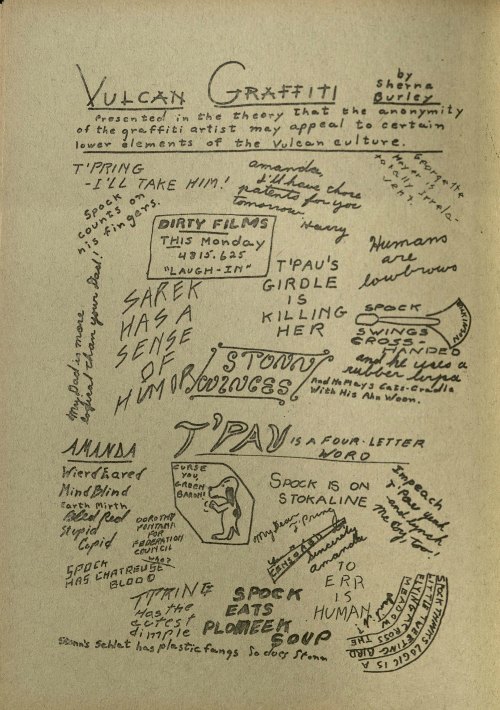

In January 2020, I traveled from Western North Carolina to the Sallie Bingham Center to study feminist newspapers in two of the Bingham Center’s incredible collections: the Women’s and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Movements (LGBT) Periodicals and Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance Periodicals collections. I was looking for material about feminist underground comics of the 1970s and ‘80s—books such as Wimmen’s Comix and Tits and Clits. I wanted to determine what feminists of the time period thought about the comics, and whether they viewed them as serious literature or just mindless entertainment.

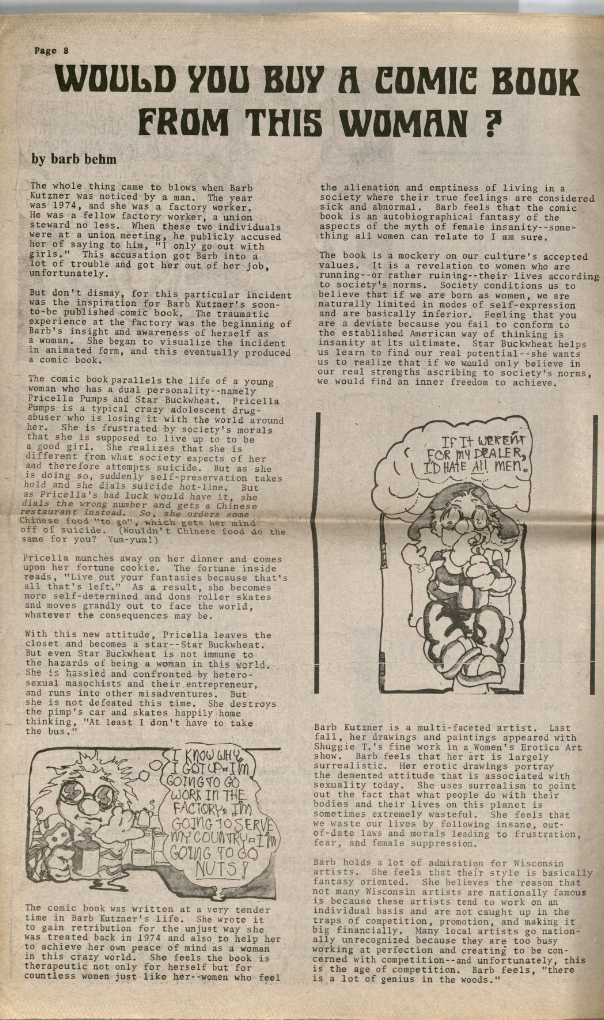

I soon found several articles that turned popular notions of comics on their heads. Most notable was a February 1976 article from the Milwaukee, Wisconsin, newspaper Amazon: A Feminist Journal. Written by Barb Behm about the now obscure Pricella Pumps/Star Buckwheat Comic Book by Barba Kutzner (1976), the article cogently praised the book’s relatability and satire of American society and its metaphorical significance for all women. Behm touted Kutzner’s protagonist as both a character with which women could heartily identify and a way to break free from the oppressive system and celebrate non-normativity.

This source was instrumental in showing that feminist underground comics, far from being tangential and lowbrow parts of the second-wave feminist movement, were instead an important part of the intellectual discourse within feminism. By finding a critic who enthusiastically engaged with the work on a level beyond its perceived lowbrow status, it became clear that some feminists viewed comics as a valid and direct medium to write and engage with feminism on a level that would not be widespread until the zine revolution of the late 1980s and early ‘90s. This reframing of comics’ literary history deepens our understanding of second-wave feminism and gives a more nuanced portrait of its discursive diversity.

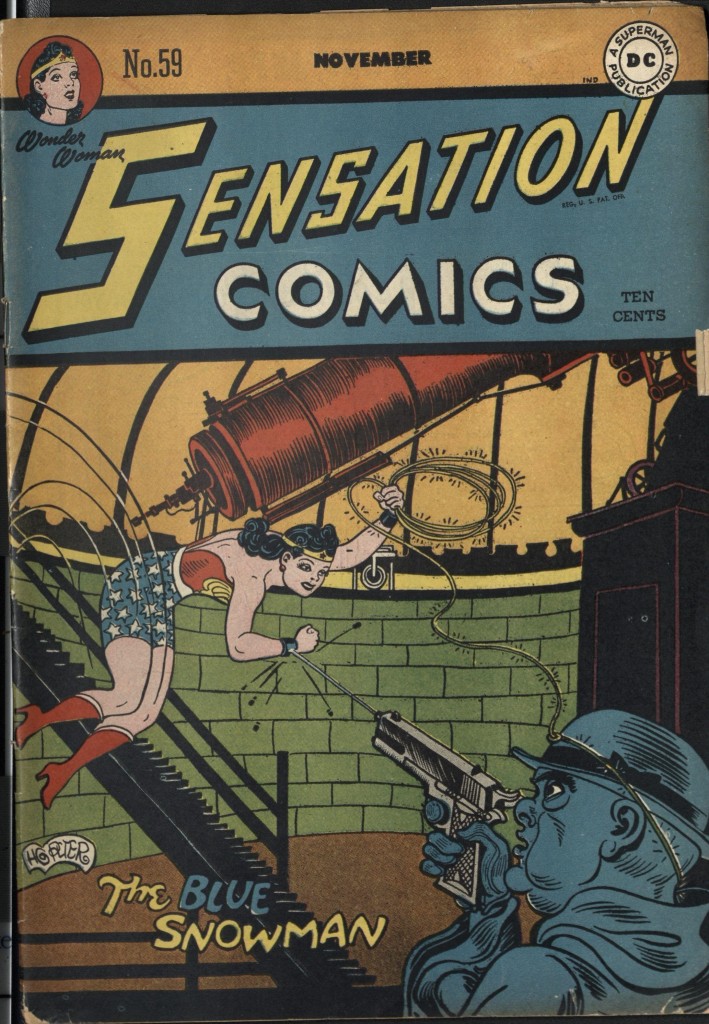

We write a lot about Wonder Woman. We write about her role(s) in nation making and myth making, her background tinged with exceptionalism and her femininity. We write about her big-screen potential, her small-screen potential, and any other mediums she might translate well to. (A serialized podcast, anyone?) What we don’t write about, or at least what we don’t write about often, are her foes—those vanquished, occasionally obliterated super villains who dared to mess with the princess of the Amazon. They are pushed to the periphery, partly hidden behind Diana Prince’s bright sun. Sometimes, however, a villain grinds his/her way back into the orbit, demanding that we take notice. The Blue Snowman is one of those villains.

We write a lot about Wonder Woman. We write about her role(s) in nation making and myth making, her background tinged with exceptionalism and her femininity. We write about her big-screen potential, her small-screen potential, and any other mediums she might translate well to. (A serialized podcast, anyone?) What we don’t write about, or at least what we don’t write about often, are her foes—those vanquished, occasionally obliterated super villains who dared to mess with the princess of the Amazon. They are pushed to the periphery, partly hidden behind Diana Prince’s bright sun. Sometimes, however, a villain grinds his/her way back into the orbit, demanding that we take notice. The Blue Snowman is one of those villains.