Post contributed by Jessica Janecki, Rare Materials Cataloger

The Project

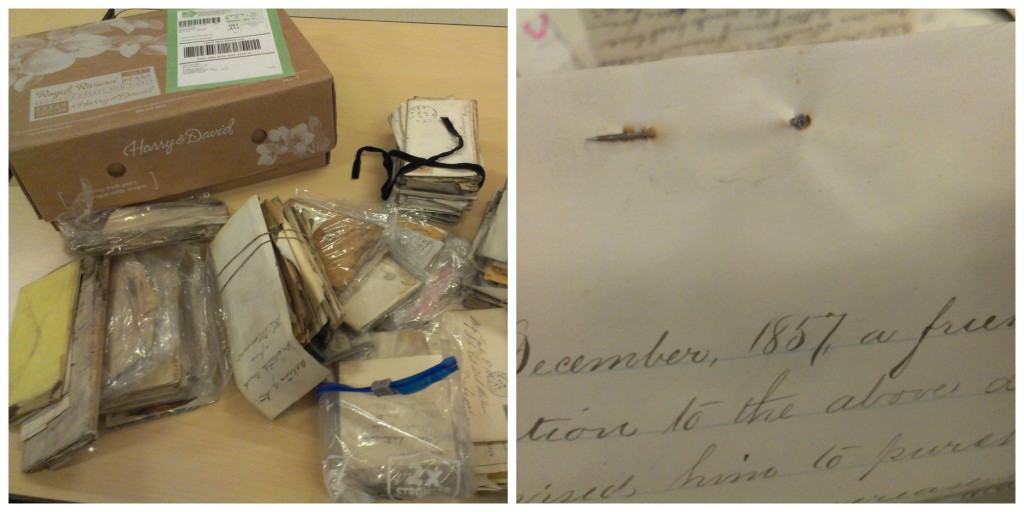

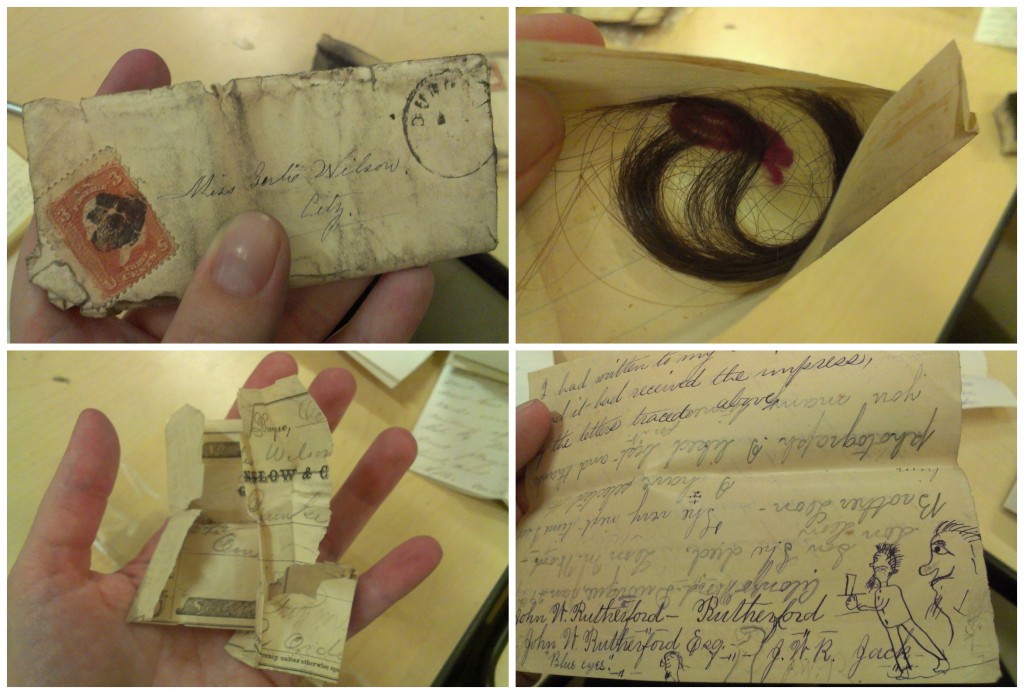

Over 200 items—bills of sale, rental agreements, “free papers,” and even one arrest warrant—make up the American Slavery Documents collection held in the Rubenstein. In Technical Services, rare materials catalogers are in the process of individually cataloging the documents in the collection.

An important part of the cataloging process involves researching the names we find in the documents so that we can correctly identify people and either associate them with their Library of Congress Name Authority File heading or create an authorized heading for them. In attempting to describe enslaved or formerly enslaved persons, the majority of whom did not have last names, we tried to do as much research as possible (is the Sue mentioned in one document the same Sue mentioned in another document? If not, how can we distinguish them?) Our hope is that by identifying and describing these individuals researchers may be able to connect them to other parts of their stories that may be contained in other repositories.

However, even with the addition of subject headings, authorized name headings, genre/form terms, and other helpful metadata, there are just some things that cannot be easily encapsulated in a catalog record. One example is the story of Lott and Frankey.

Lott and Frankey

![Transcript of recto: To all whom these presents shall come, know ye that for divers good causes and considerations me hereunto moving, but more especially in consideration of the sum of forty two pounds to me in hand paid by Lott (the waggoner) who was liberated by my deceased father Edward Carter, esq., as well as in consideration of the meritorious services of she, the wife of the said Lott, named Frankey, I have emancipated and set at liberty, and by these presents do emancipate and set at liberty my said negro slave Frankey, giving her all the privileges and [?] to which emancipated slaves are entitled under the laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia, given under my hand and seal, at the county of Albemarle, in the state of Virginia, this 25th day of June in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and one. Signed, sealed, and delivered in the presence of [blanks for witnesses] William Champe Carter Hand-written record of emancipation](http://blogs.library.duke.edu/rubenstein/files/2020/12/Frankey_Deed_of_Manumission.jpg)

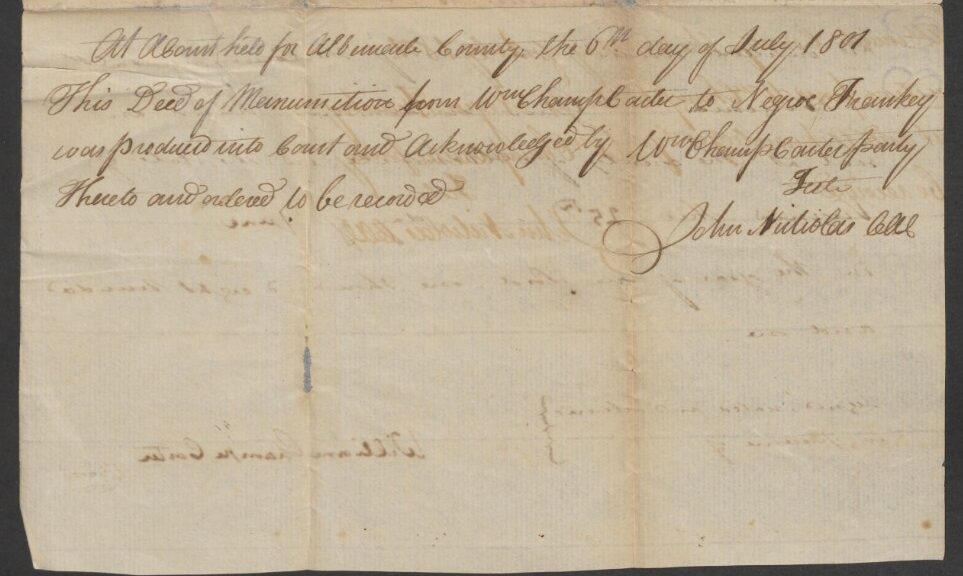

To begin this project of individually cataloging the American Slavery Documents collection, I deliberately chose one of the happier document types: this deed of manumission freeing an enslaved woman named Frankey. It is dated June 25, 1801 and was recorded at the court of Albemarle County, Virginia by clerk of court John Nicholas.

In it, William Champe Carter, Frankey’s enslaver, declares:

…in consideration of the sum of forty two pounds to me in hand paid by Lott (the waggoner) who was liberated by my deceased father Edward Carter, esq., as well as in consideration of the meritorious services of she, the wife of the said Lott, named Frankey, I have emancipated and set at liberty, and by these presents do emancipate and set at liberty my said negro slave Frankey…

In other words, Frankey’s husband Lott purchased her freedom for 42 pounds.

From this deed we know nothing else about Frankey other than her name, the name of her husband, and that in June 1801 she lived in Albemarle County, Virginia. In my research I have not been able to discover how she came to be enslaved by William Champe Carter, which of the many Carter family plantations she might have lived at, or even her approximate age.

The deed actually tells us more about Lott than Frankey. We learn that Lott had been enslaved by William Champe Carter’s father Edward Carter, who also emancipated him. When Edward Carter died in 1792, he left instructions in his will to emancipate Lott,[1] one of the few enslaved persons he mentioned by name in his will. We also learn Lott’s profession as William Champe Carter refers to Lott as “the waggoner,” which means wagon driver.

If Lott was a free man by 1792, what might he have been doing between his emancipation and when he purchased Frankey’s freedom in 1801? In the deed he is referred to as Lott “the waggoner,” suggesting that he found employment after his emancipation. I searched early Virginia property tax records (available here) and found 2 promising entries in Albemarle County. The first from 1795 reads: Negro Lott emancipated by Edwd Carter decd [ie deceased] 1 tithe 2 horses and the second from 1797 reads: Wagoner Lott free negro 1 tithe 1 horse. These entries show that the commonwealth of Virginia recognized Lott as a free man, and one who owned enough personal property to owe property taxes. The 1797 entry helpfully confirms that he worked as a wagon driver. That these tax records are from Albemarle County also shows that Lott stayed close to Frankey during the 9 years he worked to earn the 42 pounds to buy her freedom.

What happened to Frankey and Lott after 1801? In the tax records for 1803, 1805, 1806, and 1807 there are references to Lott Saunders, a “free negro.” Is this the same Lott? Unfortunately, we have no way of knowing for certain and after that the trail grows cold. Searching for any traces of Frankey are especially difficult as court documents from a lawsuit in 1821 between members of the Carter family show that at least two women still enslaved on Carter plantations were named Frankey.

If Frankey and Lott remained in Virginia after Frankey’s emancipation they would have faced challenges. William Champe Carter refers to the “privileges” to which “emancipated slaves are entitled under the laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia.” One of those “privileges” was constantly having to prove their freedom. The 1793 state law An Act for Regulating the Police of Towns in this Commonwealth, and to Restrain the Practice of Negroes Going at Large required free people of color to register with the towns where they worked or lived and pay a fee for a copy of their certificate of registration. This registration had to be renewed every year. If they could not produce their certificate they could be jailed indefinitely.

Future Connections

The story of Frankey and Lott is one of many glimpses of humanity and struggle (as well as oppression and cruelty) that can be found in the American Slavery documents collection. It is our hope that our efforts to individually catalog the documents will improve access and allow users to discover materials (and the lives that they reveal) by searching names, places, subjects, and document types in addition to browsing the digital collection. And in this process of discovery, connections will continue to be made, so that the humanity of lives lived, such as Frankey’s and Lott’s, will continue to be revealed and remembered.

Full transcription of Deed of Manumission

Transcript of recto:

To all whom these presents shall come, know ye that for divers good causes and considerations me hereunto moving, but more especially in consideration of the sum of forty two pounds to me in hand paid by Lott (the waggoner) who was liberated by my deceased father Edward Carter, esq., as well as in consideration of the meritorious services of she, the wife of the said Lott, named Frankey, I have emancipated and set at liberty, and by these presents do emancipate and set at liberty my said negro slave Frankey, giving her all the privileges and [?] to which emancipated slaves are entitled under the laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia, given under my hand and seal, at the county of Albemarle, in the state of Virginia, this 25th day of June in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and one.

Signed, sealed, and delivered in the presence of [blanks for witnesses]

William Champe Carter

Transcript of verso:

At a court held for Albemarle County the 6th day of July 1801 this deed of manumission from Wm Champe Carter to Negroe Frankey was produced into court and acknowledged by Wm Champe Carter party thereto and ordered to be recorded

Teste

John Nicholas

[1] The Carters of Blenheim: a genealogy of Edward and Sarah Champe Carter of “Blenheim” Albemarle County, Virginia. [Richmond, Va. : Garrett & Massie], 1955.