Post contributed by Laurin Penland, Library Assistant for Rubenstein Technical Services

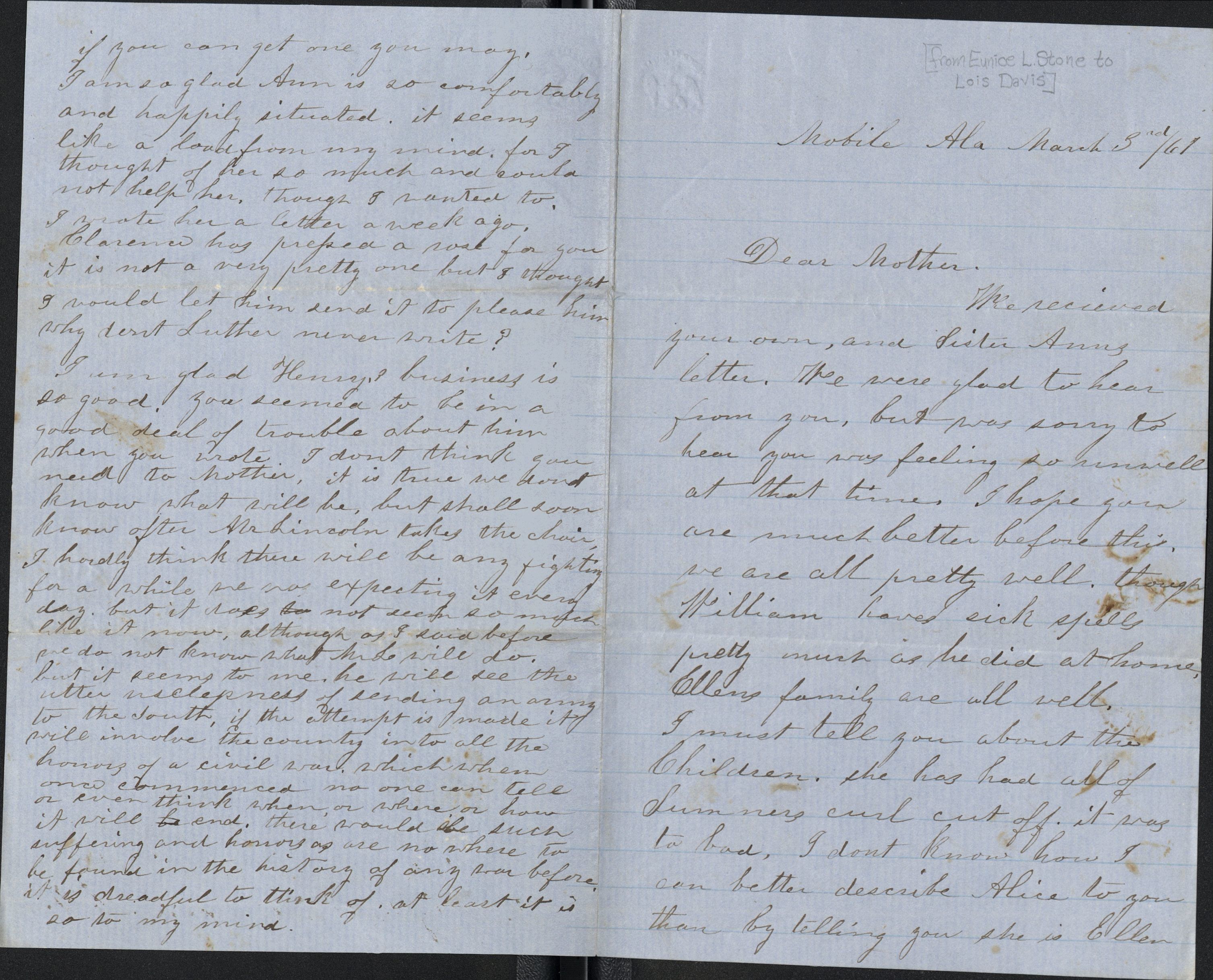

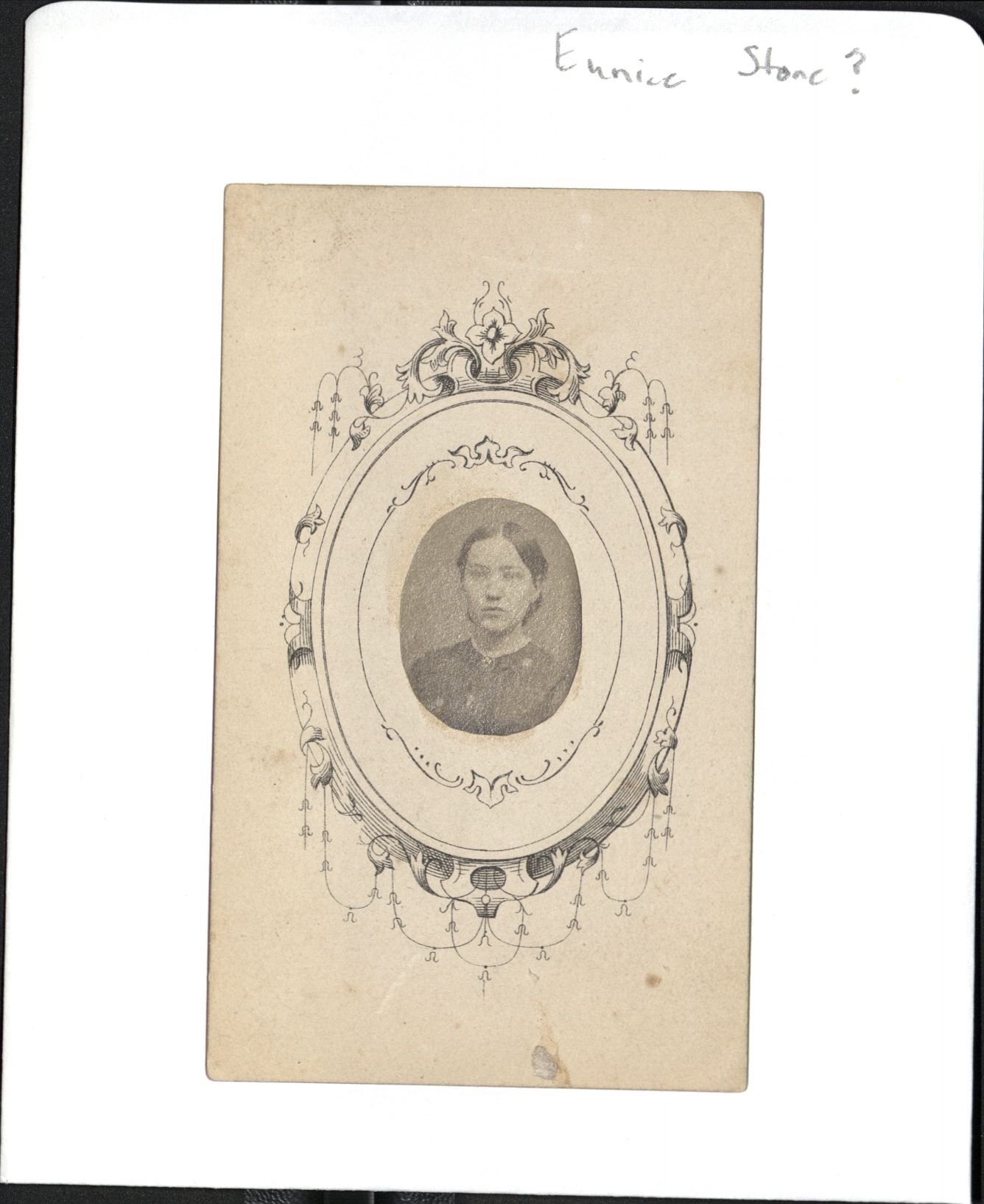

There is just too much to write about in the Lois Wright Richardson Davis family papers, a collection that tells the tale of a mother and her seven children divided by the American Civil War. For a relatively small collection (0.75 linear feet), the letters reveal many triumphs, trials, and heartbreaks, as well as many aspects of the historical and social contexts of their time. Two of Lois’s sons (and a stepson) fought for the Union, while two of her sons-in-law fought for the Confederacy. This split in the family came about just before the war, when two of Lois’s daughters (Ellen and Eunice) and their husbands decided to move from Massachusetts to Mobile, Alabama, where they hoped to find better employment prospects. Soon after they arrived, the war broke out and the sons and sons-in-law volunteered for opposing sides. Remarkably, the family members were not hostile toward one another in their letters, and often inquired after the health and safety of one another. Sometimes they even joked about their tragic situation. In one letter, daughter Eunice wrote from Mobile to her brother up North asking, “Are you coming down here to fight us?”

The bulk of the letters shared between the family members describe their experiences during the “fatal conflict” and offer valuable first-hand narratives about important battles and skirmishes. For instance, in a letter from 1863, Charles Henry, who was Lois’s eldest son and who was a soldier in the Union Army, wrote home about a harrowing battle at Sabine Pass.

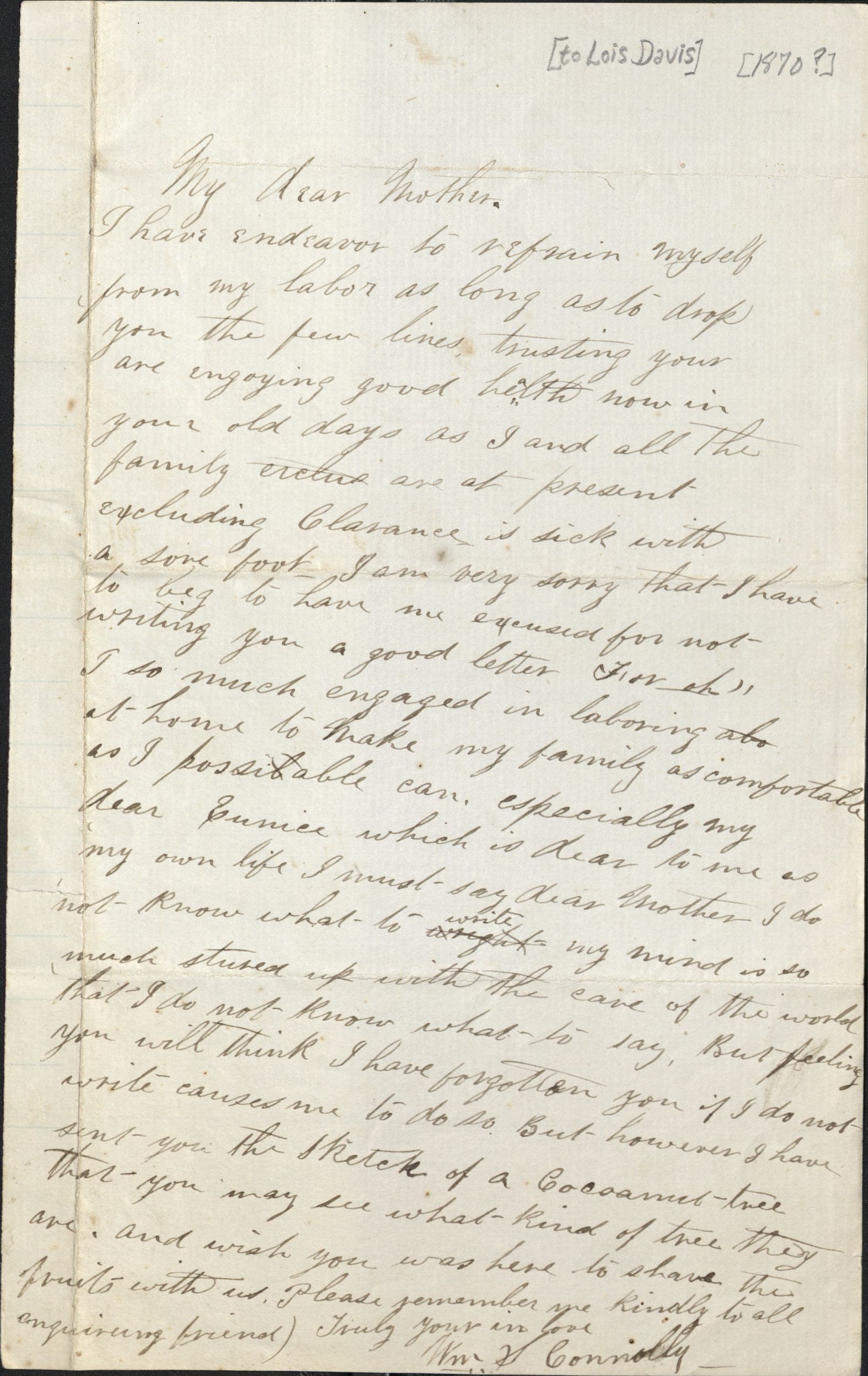

However, it would be remiss to categorize these letters as simply being about the Civil War. The family members were excellent writers, and their descriptions offer insights across many categories of human experience. For instance, the historian Martha Hodes, who wrote her dissertation on interracial romantic relationships, was drawn to Eunice’s story. During the war, Eunice’s first husband died of cholera in the Confederate Army. She struggled for many years with poverty and illness, but she remarried to a successful Afro-Caribbean sea merchant, William Smiley Connolly. They married in Massachusetts in 1869, and she moved with him and her two children to Grand Cayman. The letters document their loving relationship and their life on the island. Unfortunately, the letters also reveal that Eunice, William, and their children were killed in a hurricane.

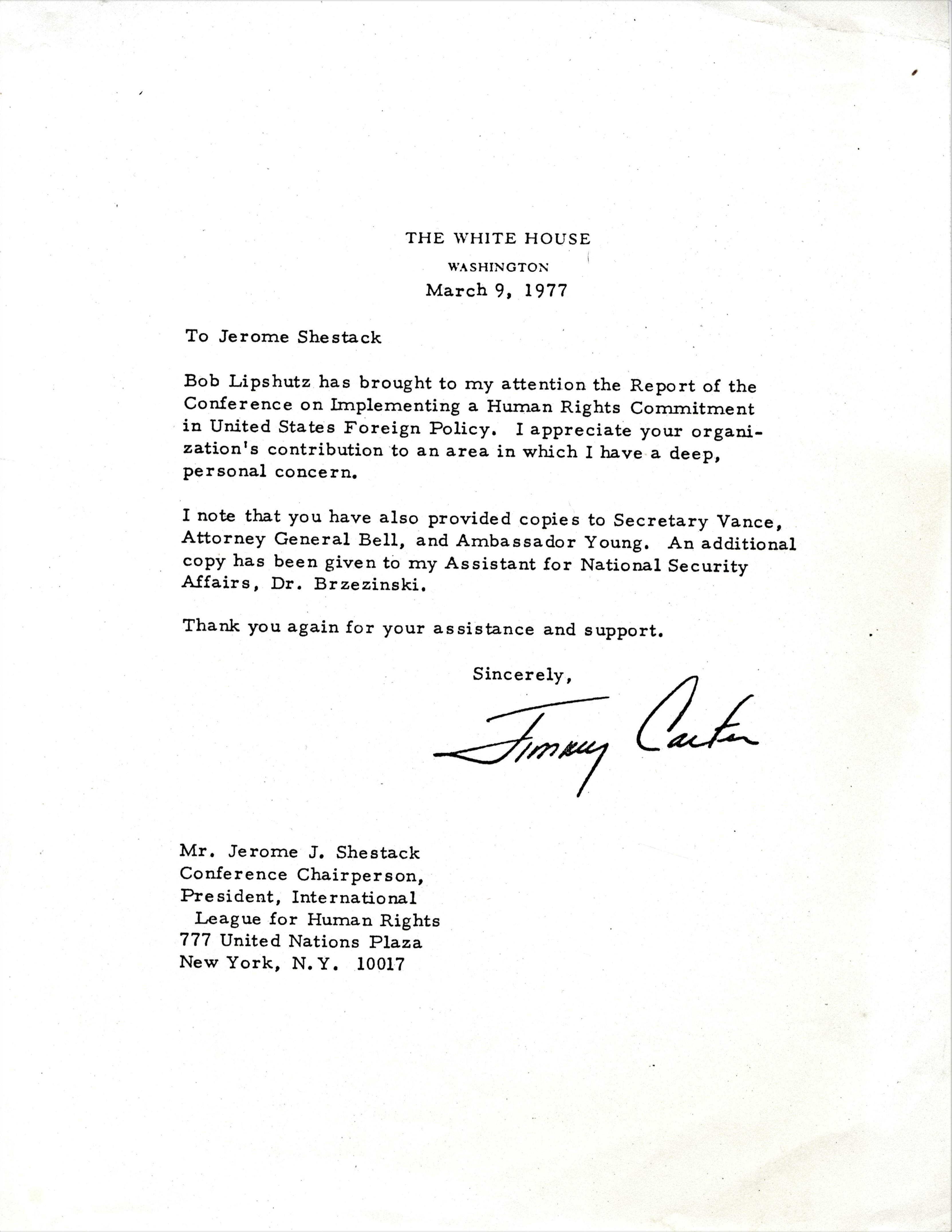

So, why am I writing about these letters now? I was searching through the old card catalog (now digitized into PDFs) at the Rubenstein for collections that may include materials about people of color. Sometimes in older collections, people of color were not included in the description, or the description that was included is outdated (and sometimes offensive). In my search, I stumbled upon the catalog record of the Lois Wright Richardson Davis papers, which mentioned William Smiley Connolly, the “black sea caption and shipowner.” Upon further inspection, it became clear that some of the description could be updated and that the letters were in over-stuffed folders, so I set out to reprocess the papers. Because one of the goals of reprocessing was to highlight certain voices that had been previously under-described, I created a collection guide with descriptions of each folder’s contents, making it easier for researchers to search for William Connelly’s letters and to find descriptions of African Americans. The collection provides valuable and often disheartening historical evidence of racism and slavery from the letter writers’ perspectives, as well as evidence of African-American contributions to the Union. I also made it more apparent that this collection not only emphasizes soldiers but also provides rich information about the lives of working-class women in the 19th century. As the years go by in the letters, the female correspondents covered many topics including illnesses, religious beliefs, child-rearing, single-motherhood, and employment. There are many surprises in the collection, many of which I tried to document in the collection guide, including one letter in particular that skims the surface of the complexity of gender.

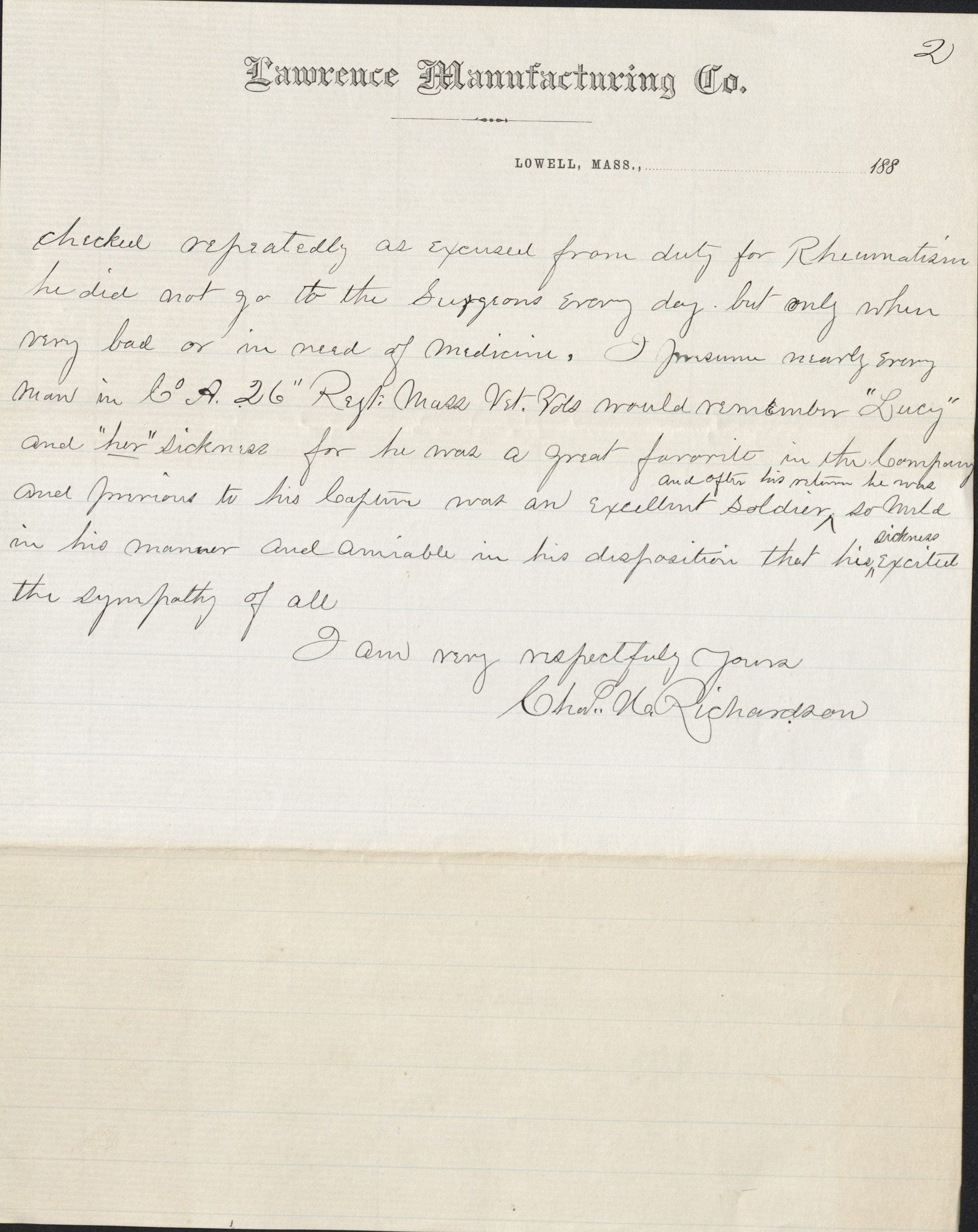

It is a letter written by Charles Henry after the war. He wrote many letters in support of veterans who were seeking pensions. One of these letters described a possibly gender-fluid, transgender, and/or gender-nonconforming soldier nicknamed “Lucy.” The letter piqued my interest because I am often looking for past evidence of LGBTQ folks in archival collections and am intrigued by situations when ordinary ways of describing sex and gender breakdown. As Charles Henry described “Lucy,” he slipped in and out of the language of the gender binary. It is difficult to tell if Charles Henry was making fun of “Lucy” in a derogatory way—for as I went through the collection, it became apparent that Charles Henry sometimes had a biting sense of humor—or if he was merely recalling a beloved fellow soldier who was “young, slim, smooth faced, and very feminine in his ways” (Charles Henry underlined certain words for emphasis). For the purposes of the letter, Charles Henry described “Lucy’s” rheumatism caused by the war and finished by saying, “I presume nearly every man in Co. A. 26th Regt. Mass. Vet. Vols would remember ‘Lucy’ and ‘her’ sickness for he was a great favorite in the company and previous to his capture was an excellent soldier and after his return he was so mild in his manner and amiable in his disposition that his sickness excited the sympathy of all.”

I could go on and on about these letters but am told that blog posts are to be somewhat brief. Plus, I want to save many of the invaluable epistolary moments of the collection for others to discover on their own. I hope that researchers, instructors, and students will continue to visit this collection and that they will be as captivated as I was by the lives that it reveals. You can learn more about the Lois Wright Richardson Davis family papers by visiting the collection guide and by visiting the Rubenstein’s reading room (open to the public). I also highly recommend Martha Hodes’s book about Eunice and William, The Sea Captain’s Wife: A True Story of Love, Race, and War in the Ninteenth Century.

Update: The Lois Richardson Davis family papers have been digitized. You can peruse the collection in the digital repository and also access digitized items in the collection guide.

reserved demonstrate the values that motivated him to join the Socialist Party, and later leave it. He eschewed party affiliation, rejecting Southern Democrats, who maintained anti-democratic policies such as the poll tax, and Socialists, whom he believed “moved so far to the leftward it is in danger of committing political ‘suicide.’”

reserved demonstrate the values that motivated him to join the Socialist Party, and later leave it. He eschewed party affiliation, rejecting Southern Democrats, who maintained anti-democratic policies such as the poll tax, and Socialists, whom he believed “moved so far to the leftward it is in danger of committing political ‘suicide.’”