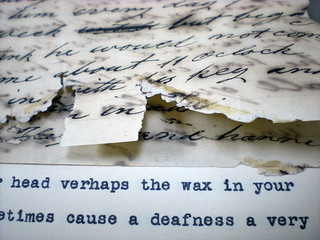

Conservation Services has been working closely with staff from our Digital Production Center this week to train in the operation of our new multispectral imaging equipment and learn about image processing. During the calibration and testing of the machine we took the opportunity to re-image the illuminated manuscript leaf which I posted on back in the summer. The palimpsest is so clearly legible in these new photos! We are very excited by the possibilities that this new imaging equipment opens for learning more about our collection materials.

Conservation Services has been working closely with staff from our Digital Production Center this week to train in the operation of our new multispectral imaging equipment and learn about image processing. During the calibration and testing of the machine we took the opportunity to re-image the illuminated manuscript leaf which I posted on back in the summer. The palimpsest is so clearly legible in these new photos! We are very excited by the possibilities that this new imaging equipment opens for learning more about our collection materials.

Category Archives: Digital Production Center

Revealing Hidden Texts

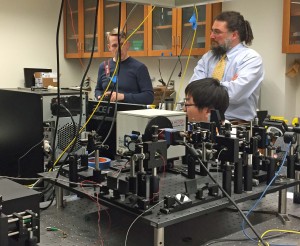

For months a group of DUL staff including Mike Adamo and Molly Bragg from the Digital Production Center, Josh Sosin and Ryan Baumann from the Duke Collaboratory for Classics Computing, and myself have been discussing the potential use of multi-spectral imaging (MSI) in our work. This week, Mike Toth and Bill Christens-Berry of R.B. Toth Associates were on campus to facilitate two days of MSI imaging.

Day 1: An alternative to scanning mice eyes

Mr. Toth’s sister, Dr. Cynthia Toth, is an ophthalmologist at the Duke Eye Center. She uses optical coherence tomography (OCT) to scan premature infants’ eyes to detect neurological and visual problems. Dr. Toth and Mr. Toth coordinated time with Dr. Sina Farsiu and his graduate student Guorong Li to image a few papyri from the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Dr. Farsiu uses OCT in his research. When he isn’t kindly imaging papyri, he is scanning mice eyes. Dr. Farsiu also coordinated time in Dr. Adam Wax’s lab in the Biomedical Engineering Department where we used their OCT scanner to image the papyri using a slightly different set up. Dr. Wax’s team is usually scanning rat esophagi and mice eyes, so a day with papyri was a bit out of their wheelhouse but everyone seemed to enjoy the collaboration. The Raleigh News & Observer was there as well and posted this story.

Mike Adamo from the DPC and I escorted the Rubenstein collection materials to the Duke Eye Center and the Biomedical Engineering lab. My role was to provide safe transportation across campus, and to handle the fragile items. Having researched OCT, I felt that this was a safe, non-destructive imaging technique for the papyri. It’s hard to say what the outcome of the OCT scanning will be, but it has potential to reveal hidden media, which is exciting to think about.

Day 2: MSI Scanning in DPC

On Wednesday, Toth and Christens-Berry set up their MSI equipment in the DUL Digital Production Center. Their system scans at a variety of UV and IR wavelengths. The Library was interested in testing a range of problems to see what this system could reveal. The materials we scanned included several papyri with obscured text, two early Hebrew manuscripts whose writing is almost completely obscured by the condition of the gevil, a bound book with a Latin manuscript paste-down that is obscured by a previously adhered bookplate, and a Greek manuscript that was scraped and written over. All of these items present common problems for researchers using ancient texts.

|

|

Proof of Concept

The work that we did on Tuesday and Wednesday was meant to provide “proof of concept” for the conversations that must happen regarding funding, staffing, training, workflows and service expectations if the Library were to develop an MSI scanning workflow.

Conservation is excited about MSI for its potential to discover more about the materials we work on. Having the ability to image in both UV and IR would expand our knowledge of the materials, expose information we can’t see with the naked eye, and enable us to envision better treatments. I think we are all excited for its potential to provide access to materials that right now cannot be easily used or read, such as the Hebrew manuscripts and the hidden texts on the papyri cartonnage. We literally had a “Holy [Cow]” moment when we saw these materials give up their secrets. It gave me goosebumps.

Mike Adamo wrote a blog post for Bitstreams describing their side of this project.

1091 Project: Secret Lives of Conservation Labs

This month on the 1091 Project we are talking tours. I recorded eight official tours so far this fiscal year. These included tours for library donors and prospective donors; the Library Council, a group of faculty that meet with the library’s Executive Group during the school year; and most recently to the Alumni Association during the annual Alumni Weekend. That tour consisted of about 20 people, but we have had as much as twice that on large tours.

This month on the 1091 Project we are talking tours. I recorded eight official tours so far this fiscal year. These included tours for library donors and prospective donors; the Library Council, a group of faculty that meet with the library’s Executive Group during the school year; and most recently to the Alumni Association during the annual Alumni Weekend. That tour consisted of about 20 people, but we have had as much as twice that on large tours.

We also give a lot of informal, spur of the moment tours that don’t make it to the “official” record. These tours are generally for new staff and interns, faculty and visiting scholars, and other interested individuals. This year we gave a tour for artist Bea Nettles, and Henry Wilhelm, of Wilhelm Imaging Research, and John Baty, a conservation scientist. Wilhelm and Baty also toured LSC and DPC.

Tours are an important development tool. They are also a chance to educate people about the work we do, why the work is important and how it relates to the mission of the Library. I love to see people’s faces light up when they realize that you can wash paper or resew a book and make it whole again. Of course the best part is showing off our highly skilled and talented staff.

I know some labs include tours in their yearly stats. I report our big tours in our fiscal year report, but I don’t record every tour we give. I would love to hear your experience with documenting tours and/or how you report tours to your administration in your year-end reports.

Let’s head to Parks Library Preservation to see what they do with tour groups.

Cleaning Radio Haiti Reel-to-Reel Tapes

This week we worked with Craig Braeden from Rubenstein Library and Zeke Graves from the Digital Production Center to test a cleaning workflow for moldy reel-to-reel audio tapes we recently received from Haiti.

Conservation doesn’t have expertise in cleaning magnetic media, so this was a chance to learn more about these materials and to do some cross training.

The method is simple enough. While the tape is running you gently hold a piece of Pellon to the tape to remove the mold. What is more difficult is learning to evaluate the tape to be sure it isn’t too fragile for this treatment, holding the tape with just enough pressure to clean it but not too much to damage it while it is moving through the deck, and watching for splices. Craig brought over an old deck and we set it up in the fume hood in Conservation. Zeke helped clean and repair the tape when we encountered previous splices.

Craig has posted a brief video on the Devil’s Tale about this collection and what it will take to clean, digitize and make it accessible.

Last Chance To See “What’s Missing From Your Video History”

This week will be your last opportunity to see our exhibit “What’s Missing From Your Video History” sponsored by the Preservation Department and the Digital Scholarship and Production Services.

This week will be your last opportunity to see our exhibit “What’s Missing From Your Video History” sponsored by the Preservation Department and the Digital Scholarship and Production Services.

Audio-visual materials’ rapid deterioration (relative to print media), its wide adoption for commercial and personal use, and the range of formats and playback equipment that rose and fell around analog videotape, have profound implications for preserving those pieces of our 20th century history that were captured on videotape.

The exhibit is on Perkins Lower Level 1, outside the Digital Production Center, near room 023. Open during library hours.

New Exhibit: What’s missing from your video history?

Written by Liz Milewicz, Ph.D, Head of Digital Scholarship and Production Services. Exhibit curated by Liz Milewicz and Winston Atkins, Preservation Officer.

Calling up my favorite Bert and Ernie sketches on YouTube makes it seem like there’s no problem with accessing my video history. But a brief glance behind the institutional curtains of digital preservation casts a cloud on how often I’ll be able to revisit such happy scenes.

Calling up my favorite Bert and Ernie sketches on YouTube makes it seem like there’s no problem with accessing my video history. But a brief glance behind the institutional curtains of digital preservation casts a cloud on how often I’ll be able to revisit such happy scenes.

Audio-visual materials’ rapid deterioration (relative to print media), its wide adoption for commercial and personal use, and the range of formats and playback equipment that rose and fell around analog videotape, have profound implications for preserving those pieces of our 20th century history that were captured on videotape.

“Generation Loss,” a new exhibit that I’ve co-curated with Winston Atkins, Preservation Officer, presents just a few of the many videotape formats introduced during the 20th century and collected in Duke University Libraries, as well as the signs of their deterioration and the factors that contribute to their loss. Because some of these signs are only visible when the tape is played, much of this loss goes unseen and unknown until someone tries to play the tape. The video display in this exhibit demonstrates some of common signs of audio-visual deterioration.

The exhibit is open during regular Perkins/Bostock hours. We are located on the Lower Level (same level as the Link), by Perkins Room 023. Come and have a look!

1091 Project: Digitization and Conservation

Welcome to this month’s 1091 Project wherein Parks Library Preservation and Preservation Underground talk about how we collaborate with our respective digitization programs.

Welcome to this month’s 1091 Project wherein Parks Library Preservation and Preservation Underground talk about how we collaborate with our respective digitization programs.

Where Digitization Happens

At Duke Libraries digitization happens in three departments:

- Winston Atkins, head of the Preservation Department, advises on and coordinates preservation reformatting projects for both born digital collections and analog materials (especially non-print materials such as moving image).

- The staff in the Digital Production Center (DPC) is part of the Digital Scholarship and Production Services Department headed by Liz Milewicz. DPC digitizes print, manuscript and A/V materials for both library-driven projects and individual patron requests. They use a variety of imaging hardware in their workflow, choosing the appropriate one based on the size, condition and type of material they are imaging.

- Internet Archive has one operator and overhead-scanning equipment on site to digitize print materials from special collections.

Conservation Services works to some extent with all three of these workflows to be sure our materials are safe and in good condition for imaging.

Project Evaluation Prior To Imaging

We review projects under consideration for digitization to be sure the materials are stable enough for reformatting. We meet with DPC and library staff to look at the collection (or a representational portion of it if it is very large) to determine what kind of materials they are, what their condition is, and what treatment may be needed prior to digitization.

Treatment Before And After Imaging

Our main concern is that damaged materials are stabilized prior to reformatting so they can be handled without further deterioration. The most common problems that we treat before imaging include:

- page tears or losses

- mis-folds or detached pieces of fold-outs

- loose or detached pages

- old repairs (if they obscure text)

- uncut pages

- old Mylar encapsulations sealed with tape

We don’t normally fix binding problems such as loose or missing spines or boards until after imaging if the book can be handled carefully as is. But if we feel a book should be repaired first, we will consult with the librarians and decide on a treatment plan prior to sending it to DPC.

After imaging we will do any repairs or put those items into our repair request database to do at a later date. We will also provide a custom enclosure for anything that is fragile or needs protection, just as we would for any other treatment in the lab.

An example of a pre-imaging workflow is the ongoing broadside project. Decades ago it was standard practice to tape the edges of the broadsides to protect them from tearing (we obviously don’t do that anymore). Over the years, the adhesive has made the paper very brittle, yet it is still sticky. DPC cannot image through Mylar so the old, double-stick tape encapsulations must be removed. Because of time and resource limitations we do not remove the old tape, but we do repair any heavily damaged broadsides with paste and Japanese tissue so that they are in one piece and readable. When DPC is finished with them, we re-encapsulate the taped broadsides with our ultrasonic welder so that they do not stick to other broadsides in the folder (no more tape!).

Collaboration During Imaging

The Internet Archive is scanning an incredible number of items every day. The most often requested repairs for this workflow is cutting pages that were never cut by the publisher, or reattaching a loose page. We try to turn these around quickly to keep this workflow moving, especially if it is a patron request.

Sometimes a page or fold-out will get torn or come loose during scanning or a book is discovered to have uncut pages. DPC will bring it next door and we will quickly turn these repairs around so we don’t hold up their workflow.

Sometimes the materials themselves pose a handling challenge and we will help physically handle the books or manuscripts during imaging. Digitizing the Ethiopic scrolls is a good example of this sort of collaboration. Because these vellum scrolls were so long they could not be imaged in one shot, and they were so tightly wound that they would roll up on their own if not weighted down.We had to devise a method to hold sections of the scrolls open while also allowing us to unroll and re-roll as we digitized.

Training

As you can imagine there is a huge volume of materials being imaged every day here in the basement of the library. Because there is so much going through DPC and Internet Archive, we simply cannot review every binding or manuscript page prior to imaging. We work very closely with the staff to be sure that they know what sort of damage to look for, how to handle fragile materials, and when to ask for assistance. We want them to feel that they have the information they need to safely handle materials, and in turn we trust their judgment to know when they should come next door to see us. I think we have a really good working relationship in this way.

Please visit Parks Library Preservation to see how they collaborate with digital projects.

Repairing de Bry, One Piece At A Time

Written by Erin Hammeke, Conservator for Special Collections.

I recently completed the treatment of three separate volumes from Theodor de Bry’s account of the Americas, and I thought I would share an anecdote from the treatment of one of the volumes, Das vierdte Buch von der Neuwen Welt (Frankfurt, 1594).

This item has an engraved map of the Florida coast and Gulf of Mexico bound in at the front of the text. The curators informed me that this map was missing about a half of the complete printed map, the whole right side. They felt that it would be useful to indicate to researchers just how much of the map was missing by doing a repair and fill to the original dimensions of the plate.

This item has an engraved map of the Florida coast and Gulf of Mexico bound in at the front of the text. The curators informed me that this map was missing about a half of the complete printed map, the whole right side. They felt that it would be useful to indicate to researchers just how much of the map was missing by doing a repair and fill to the original dimensions of the plate.

An interesting thing happened. There was a small fragment, apparently tucked in with the map that I assumed belonged along the torn edge, but upon closer inspection, did not appear to line up with any part of the map along that edge.

Lucky for us, UNC Wilson Library has a version of this volume with a complete map. We contacted our conservation colleagues at UNC and arranged to see the map at their conservation lab. I took an image of the fragment with me to see if we could place it while we were there, but we couldn’t, so, we took a digital photograph of their map in its entirety and headed back to our lab.

I blew up the digital image and printed it out to the actual dimensions of the original, and I superimposed this printout onto our partial map on a light table. I was surprised to find that the small fragment actually belonged near to the center of the missing portion of the plate.

After some head-scratching, the curators and I decided that it was best to adhere the fragment in its rightful place. Again, using the light-table and printout as a guide, I adhered it precisely where it belonged.

I was pleased to be able to share this project with scholars who use these works at a recent symposium dedicated to the latest issue of the Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies. And I am happy to say that all three of the treated volumes were recently digitized by the Digital Production Center and are now available through the library’s catalog.

Here is a picture of the map after washing, lining, repairing, and adhering the loose fragment with paste.

Learning On The Job

Recently Alex from the Digital Production Center came by to ask if I could fix a cassette tape. The tape broke while they were digitizing it, and they just needed it to hold together long enough to record Side B. I know a lot about the chemical and physical make-up of magnetic tapes, but I have never had to actually fix one before.

Recently Alex from the Digital Production Center came by to ask if I could fix a cassette tape. The tape broke while they were digitizing it, and they just needed it to hold together long enough to record Side B. I know a lot about the chemical and physical make-up of magnetic tapes, but I have never had to actually fix one before.

Librarian skills activate! I searched the professional literature and the internet to no avail. There are a lot of DIY articles on the web, but we try to hold ourselves to a higher standard in our lab whenever possible. I finally called a friend who actually does this for a living.

Hannah Frost, Manager of the Stanford University Media Preservation Lab, walked me through how to repair the tape and assured me that I had the skills necessary to do it correctly. In the end the repair took less than ten minutes, and now I know how to do this the next time it happens.

Hannah Frost, Manager of the Stanford University Media Preservation Lab, walked me through how to repair the tape and assured me that I had the skills necessary to do it correctly. In the end the repair took less than ten minutes, and now I know how to do this the next time it happens.

The thing about working in a library is that we collect everything from the usual stuff like paper and skins but we also have poison arrows, glass plate negatives, hair, textiles, paintings, glass eyeballs and magnetic media. I can’t tell you how important it is for a library conservator to create a large network of friends and colleagues who specialize in areas that are not your own. Sooner or later you will find yourself working on something completely different and unknown, and you need to know who to call. Thanks Hannah, I owe you a drink at the next AIC conference.

Building the Broadside Digital Collection

We are currently digitizing our broadside collection. Before they go to the Digital Production Center, Conservation must prepare them by removing the old encapsulations and making sure they can be handled. There is additional information on this project over at the Digital Collections Blog.

Building the Broadsides Collection, Pt. 1

Building the Broadsides Collection, A large-scale digitization approach

Wow! This Job Sure Keeps Us Hopping

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=heo_NcFnnfY