Post authored by Jen Jordan, Digital Collections Intern.

Hello, readers. This marks my third and final blog as the Digital Collections intern, a position that I began in June of last year.* Over the course of this internship I have been fortunate to gain experience in nearly every step of the digitization and digital collections processes. One of the things I’ve come to appreciate most about the different workflows I’ve learned about is how well they accommodate the variety of collection materials that pass through. This means that when unique cases arise, there is space to consider them. I’d like to describe one such case, involving a pretty remarkable collection.

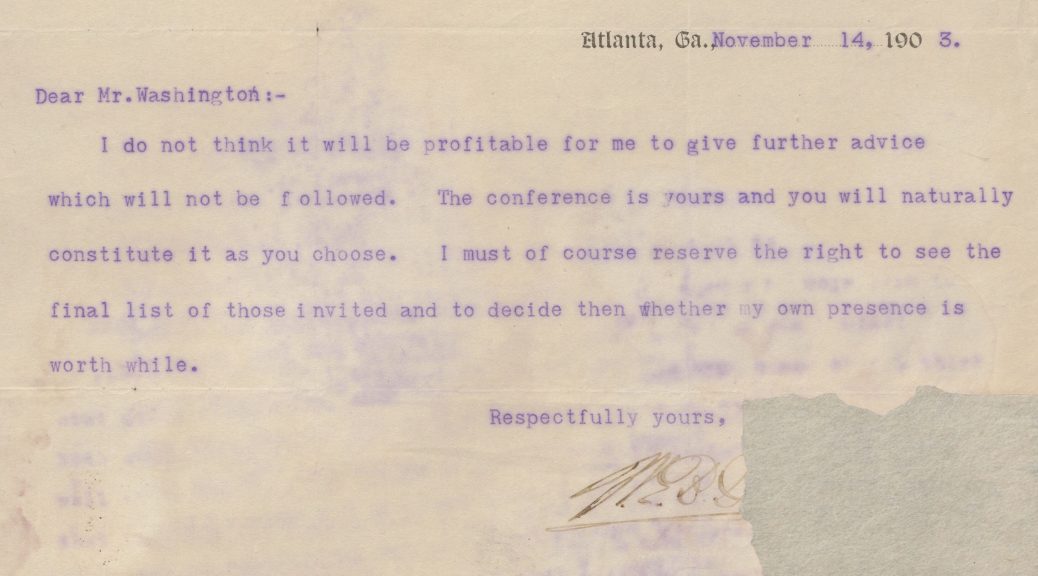

In early October I arrived to work in the Digital Production Center (DPC) and was excited to see the Booker T. Washington correspondence, 1903-1916, 1933 and undated was next up in the queue for digitization. The collection is small, containing mostly letters exchanged between Washington, W. E. B. DuBois, and a host of other prominent leaders in the Black community during the early 1900s. A 2003 article published in Duke Magazine shortly after the Washington collection was donated to the John Hope Franklin Research Center provides a summary of the collection and the events it covers.

Arranged chronologically, the papers were stacked neatly in a small box. Having undergone undergone extensive conservation treatments to remediate water and mildew damage, each letter was sealed in a protective sleeve. As I scanned the pages, I made a note to learn more about the relationship between Washington and DuBois, as well as the events the collection is centered around—the Carnegie Hall Conference and the formation of the short-lived Committee of Twelve for the Advancement of the Interests of the Negro Race. When I did follow up, I was surprised to find that remarkably little has been written about either.

As I’ve mentioned before, there is little time to actually look at materials when we scan them, but the process can reveal broad themes and tone. Many of the names in the letters were unfamiliar to me, but I observed extensive discussion between DuBois and Washington regarding who would be invited to the conference and included in the Committee of Twelve. I later learned that this collection documents what would be the final attempt at collaboration between DuBois and Washington.

Once scanned, the digital surrogates pass through several stages in the DPC before they are prepared for ingest into the Duke Digital Repository (DDR); you can read a comprehensive overview of the DPC digitization workflow here. Fulfilling patron requests is top priority, so after patrons receive the requested materials, it might be some time before the files are submitted for ingest to the DDR. Because of this, I was fortunate to be on the receiving end of the BTW collection in late January. By then I was gaining experience in the actual creation of digital collections—basically everything that happens with the files once the DPC signals that they are ready to move into long term storage.

There are a few different ways that new digital collections are created. Thus far, most of my experience has been with the files produced through patron requests handled by the DPC. These tend to be smaller in size and have a simple file structure. The files are migrated into the DDR, into either a new or existing collection, after which file counts are checked, and identifiers assigned. The collection is then reviewed by one of a few different folks with RL Technical Services. Noah Huffman conducted the review in this case, after which he asked if we might consider itemizing the collection, given the letter-level descriptive metadata available in the collection guide.

I’d like to pause for a moment to discuss the tricky nature of “itemness,” and how the meaning can shift between RL and DCCS. If you reference the collection guide linked in the second paragraph, you will see that the BTW collection received item-level description during processing—with each letter constituting an item in the collection. The physical arrangement of the papers does not reflect the itemized intellectual arrangement, as the letters are grouped together in the box they are housed in. When fulfilling patron reproduction requests, itemness is generally dictated by physical arrangement, in what is called the folder-level model; materials housed together are treated as a single unit. So in this case, because the letters were grouped together inside of the box, the box was treated as the folder, or item. If, however, each letter in the box was housed within its own folder, then each folder would be considered an item. To be clear, the papers were housed according to best practices; my intent is simply to describe how the processes between the two departments sometimes diverge.

Processing archival collections is labor intensive, so it’s increasingly uncommon to see item-level description. Collections can sit unprocessed in “backlog” for many years, and though the depth of that backlog varies by institution, even well-resourced archives confront the problem of backlog. Enter: More Product, Less Process (MPLP), introduced by Mark Greene and Dennis Meissner in a 2005 article as a means to address the growing problem. They called on archivists to prioritize access over meticulous arrangement and description.

The spirit of folder-level digitization is quite similar to MPLP, as it enables the DPC to provide access to a broader selection of collection materials digitized through patron requests, and it also simplifies the process of putting the materials online for public access. Most of the time, the DPC’s approach to itemness aligns closely with the level of description given during processing of the collection, but the inevitable variance found between archival collections requires a degree of flexibility from those working to provide access to them. Numerous examples of digital collections that received item-level description can be found in the DDR, but those are generally tied to planned efforts to digitize specific collections.

Because the BTW collection was digitized as an item, the digital files were grouped together in a single folder, which translated to a single landing page in the DDR’s public user interface. Itemizing the collection would give each item/letter its own landing page, with the potential to add unique metadata. Similarly, when users navigate the RL collection guide, embedded digital surrogates appear for each item. A moment ago I described the utility of More Product Less Process. There are times, however, when it seems right to do more. Given the research value of this collection, as well as its relatively small size, the decision to proceed with itemization was unanimous.

Itemizing the collection was fairly straightforward. Noah shared a spreadsheet with metadata from the collection guide. There were 108 items, with each item’s title containing the sender and recipient of a correspondence, as well as the location and date sent. Given the collection’s chronological physical arrangement, it was fairly simple to work through the files and assign them to new folders. Once that was finished, I selected additional descriptive metadata terms to add to the spreadsheet, in accordance with the DDR Metadata Application Profile. Because there was a known sender and recipient for almost every letter, my goal was to identify any additional name authority records not included in the collection guide. This would provide an additional access point by which to navigate the collection. It would also help me to identify death dates for the creators, which determines copyright status. I think the added time and effort was well worth it.

This isn’t the space for analysis, but I do hope you’re inspired to spend some time with this fascinating collection. Primary source materials offer an important path to understanding history, and this particular collection captures the planning and aftermath of an event that hasn’t received much analysis. There is more coverage of what came after; Washington and DuBois parted ways, after which DuBois became a founding member of the Niagara Movement. Though also short lived, it is considered a precursor to the NAACP, which many members of the Niagara Movement would go on to join. A significant portion of W. E. B. DuBois’s correspondence has been digitized and made available to view through UMass Amherst. It contains many additional letters concerning the Carnegie Conference and Committee of Twelve, offering additional context and perspective, particularly in certain correspondence that were surely not intended for Washington’s eyes. What I found most fascinating, though, was the evidence of less public (and less adversarial) collaboration between the two men.

The additional review and research required by the itemization and metadata creation was such a fascinating and valuable experience. This is true on a professional level as it offered the opportunity to do something new, but I also felt moved to understand more about the cast of characters who appear in this important collection. That endeavor extended far beyond the hours of my internship, and I found myself wondering if this is what the obsessive pursuit of a historian’s work is like. In any case, I am grateful to have learned more, and also reminded that there is so much more work to do.

Click here to view the Booker T. Washington correspondence in the Duke Digital Repository.

*Indeed, this marks my final post in this role, as my internship concludes at the end of April, after which I will move on to a permanent position. Happily, I won’t be going far, as I’ve been selected to remain with DCCS as one of the next Repository Services Analysts!

Sources

Cheyne, C.E. “Booker T. Washington sitting and holding books,” 1903. 2 photographs on 1 mount : gelatin silver print ; sheets 14 x 10 cm. In Washington, D.C., Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004672766/

One thought on “Respectfully Yours: A Deep Dive into Digitizing the Booker T. Washington Collection”

Comments are closed.