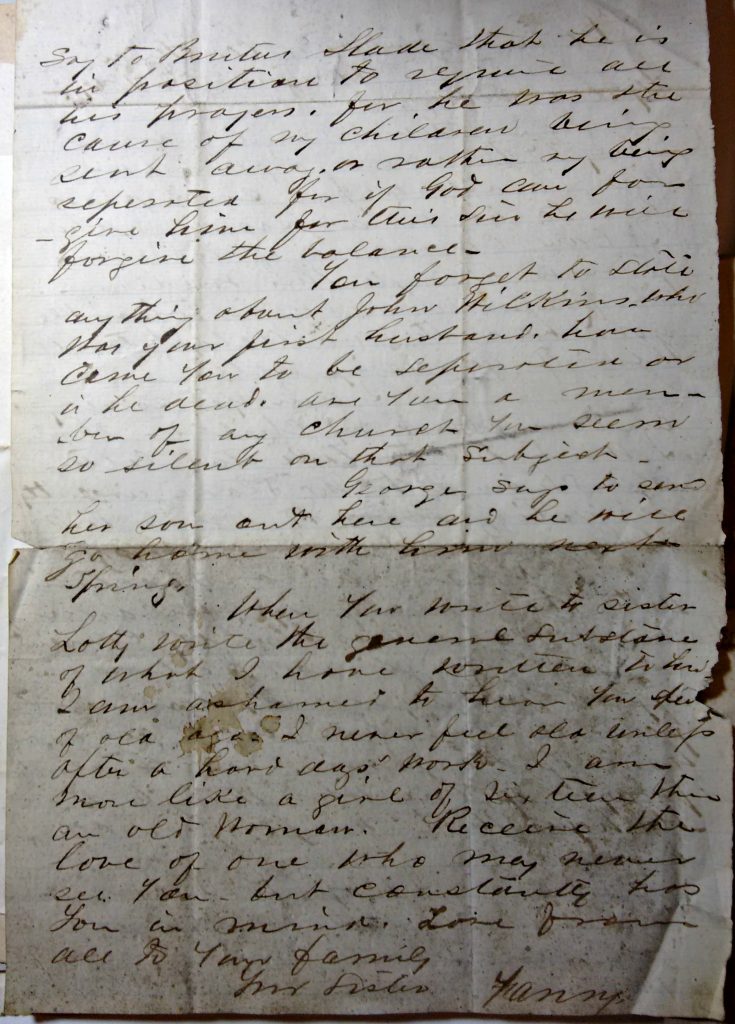

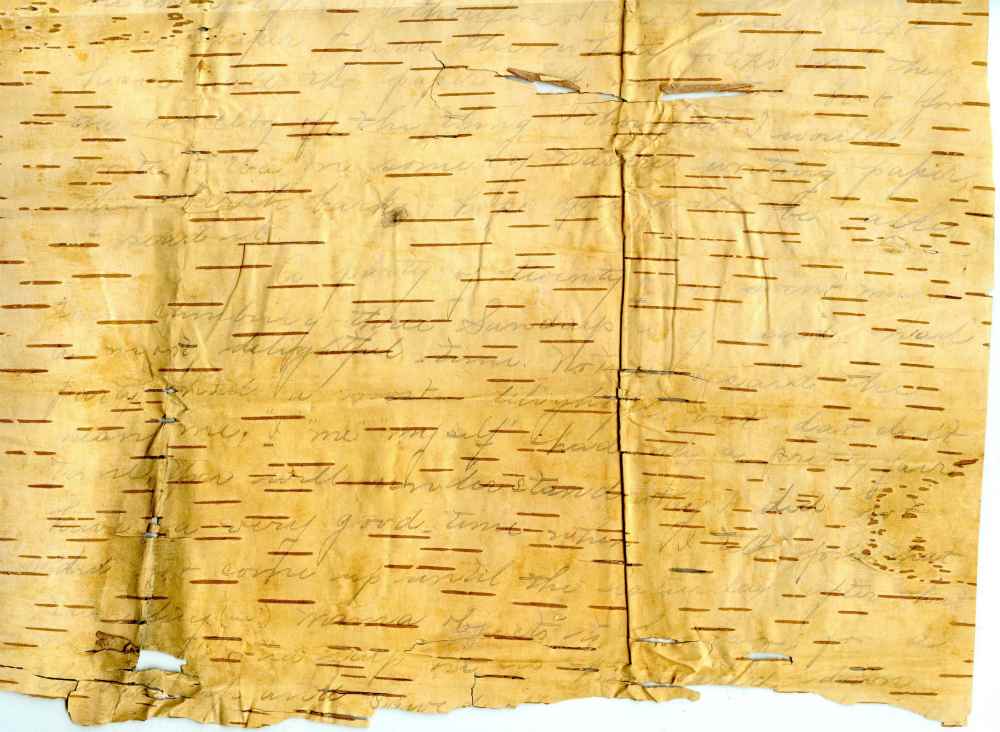

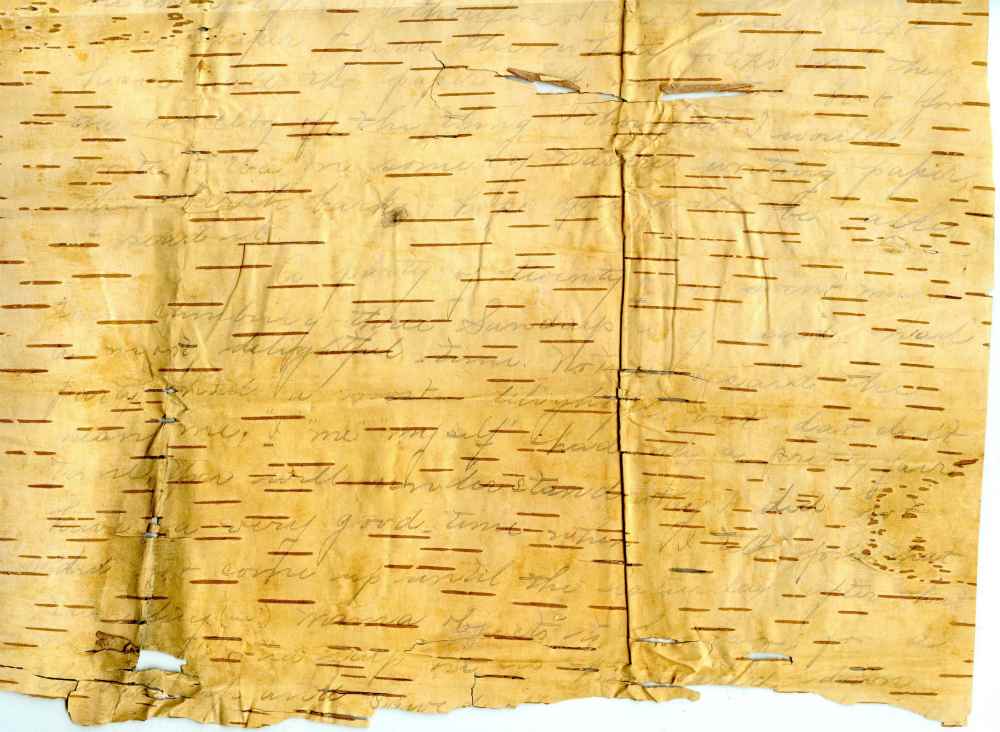

I wanted to share one of the most powerful letters I’ve seen while working here at the Rubenstein Library: a letter from Fanny, a former slave, writing from Texas in 1867 (149 years ago today!). Here’s the letter. (Click to enlarge; transcript below.)

Texana, Jackson Co., Texas, August 5th, 1867

Dear Sister,

Your kind favor of a July 3rd to hand a few days ago, it affords me such pleasure to be in a position where I can converse, if not in person through this medium. it found us all in tolerable good health and delighted to hear of [your?] being well.

I am yet so very anxious about my children that I want you to take this letter and show it to Mr Slade urgently requesting him to write to Mr J. Paul Jones (to above address.) stating all he knows in connection with the sale of my children and Mr Jones has kindly consented to write for me. He could not afford me a greater pleasure or favor and in return beg to assure him of the fervent and constant prayer of one who though humble hopes that her prayers are heard.

I hope to have a longer letter the next time for paper must be scarce in your section.

Say to Brother Slade that he is in position to require all his prayers, for he was the cause of my children being sent away, or rather my being separated, for if God can forgive him for this sin he will forgive the balance —

You forget to state anything about John Wilkins, who was your first husband. how came you to be separated or is he dead. are you a member of any church you seem so silent on that subject.

George says to send his son out here and he will go home with him next spring.

When you write to sister Lotty write the general substance of what I have written to her. I am ashamed to hear you [?] of old age. I never feel old unless after a hard day’s work. I am more like a girl of sixteen than an old woman. Receive the love of one who may never see you, but constantly has you in mind. Love from all to your family.

Your sister,

Fanny

Unfortunately we don’t have the letter’s envelope, so I don’t know who Fanny’s writing to. Although she addresses her sister, I can’t be sure they’re actual relatives. I don’t know Fanny’s last name. I don’t know her sister’s name, or where her sister lives. I’m not sure which Mr. Slade she’s referring to, or where he lived (it could be North Carolina, Georgia, or somewhere else). There’s a lot I don’t know about the people in this letter. But, one thing is very clear: Fanny’s looking for her children. The Slades sold them away, or sold her away, at some point before 1865. This letter is concrete, powerful evidence of the devastating impact slavery had on African American families, with ramifications lasting long after the the end of the Civil War.

I found this letter breathtakingly sad. I couldn’t stop thinking about Fanny. Did she ever find her children? All I could know for sure was that her sister did show the letter to Mr. Slade — because now it is held in the Slade Family Papers. But, unfortunately, I found no further correspondence with Fanny or J. Paul Jones in the collection.

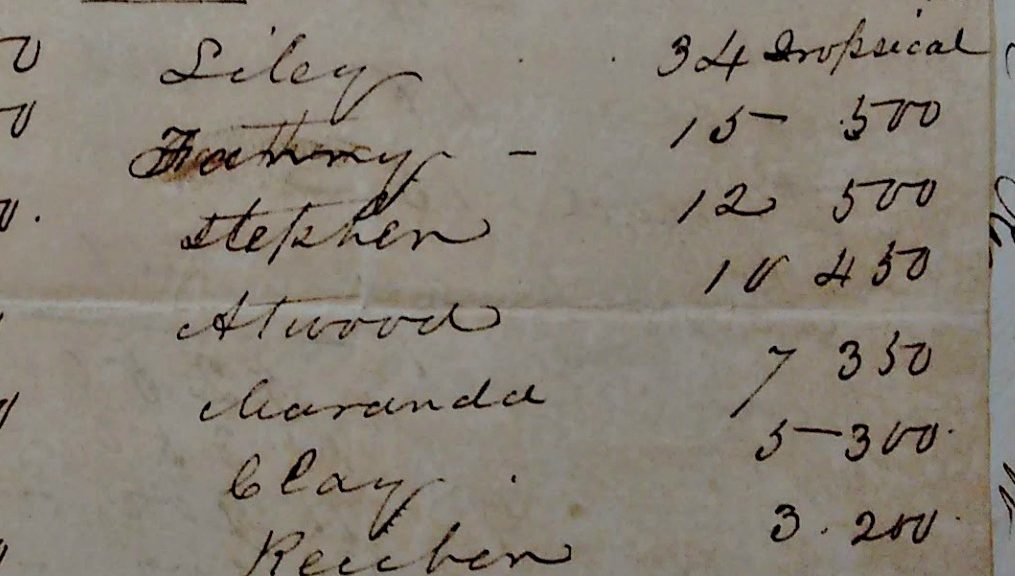

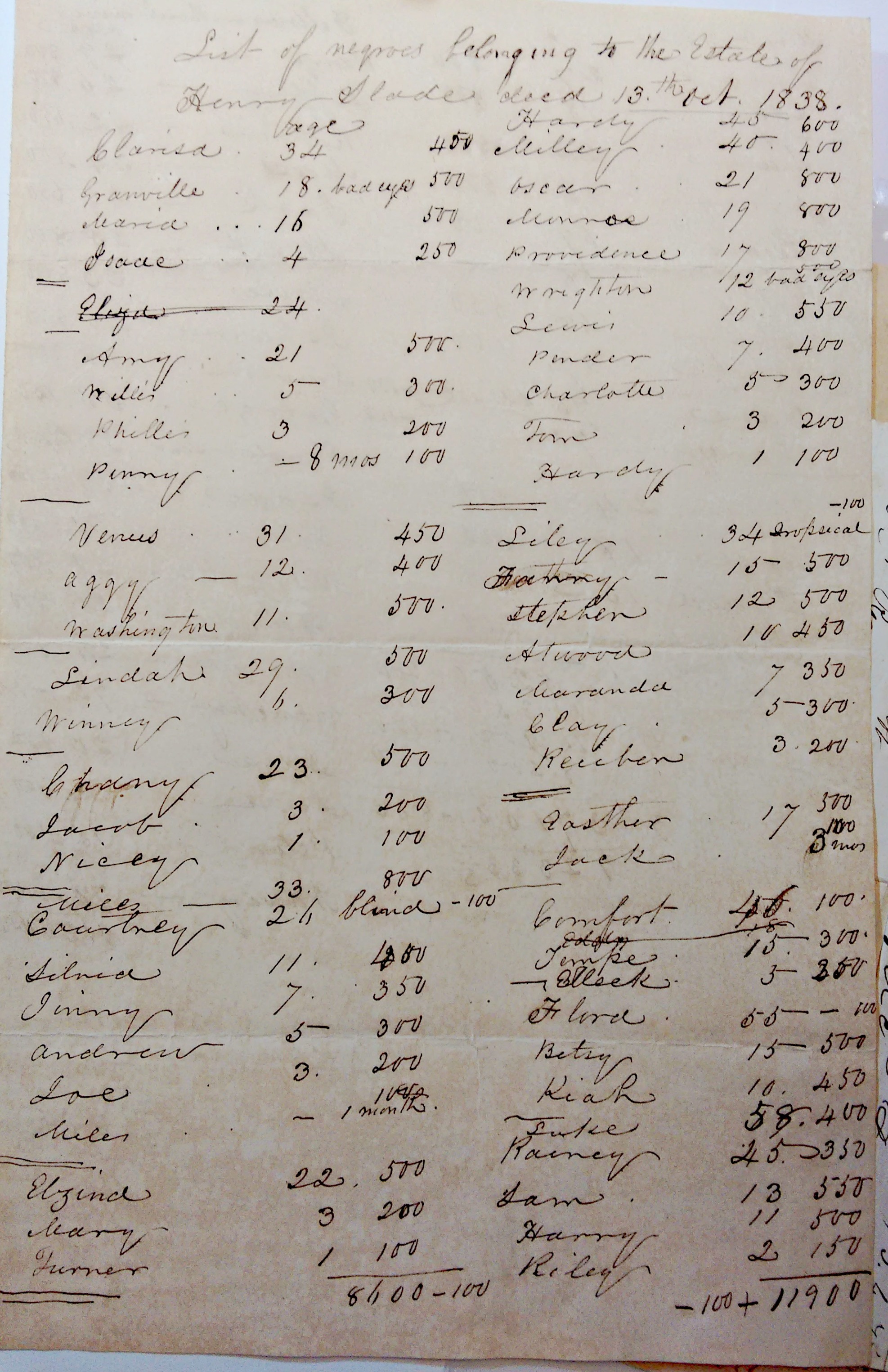

I decided to look for circumstantial evidence instead. I returned to the pre-war years of the Slade Family Papers to look for evidence of her existence in the plantation records. Despite being able to trace many of the slaves owned by the Slades from the 1830s through the 1860s, Fanny was a mystery. The only hint of a slave named Fanny lies in this estate inventory for Henry Slade, who died in 1838.

The majority of the papers in the collection stem from Thomas B. Slade and William Slade, two brothers who appear to have inherited the majority of Henry Slade’s estate. In 1838, Fanny was 15, and the estate inventory suggests she was unmarried and had no children. She is listed in what appears to be a family group with Liley (presumably her mother), Stephen, Atwood, Maranda, Clay, and Reuben. Fanny does not appear on William B. Slade’s slave census for 1850, and is not listed on his slave inventories for 1861 or 1864. My guess is that Henry Slade’s Fanny was separated from her mother and siblings shortly after 1838. I base this theory on an undated slave valuation scrap that I found tucked into William Slade’s account book.

It has the same names and similar ages as the Henry Slade estate inventory, except several slaves, including Fanny, are missing. I’m guessing this scrap represents the slaves that William Slade acquired as part of the settling of Henry’s estate around 1838. It’s possible that Fanny, Stephen, Atwood, and Maranda moved with Thomas B. Slade down to Georgia, where he ran the Clinton Female Seminary. It appears that Liley, Clay, and Reuben were transferred to William Slade and stayed in Martin County, North Carolina. Clay and Reuben continue to show up on William Slade’s accounts in the 1850s.

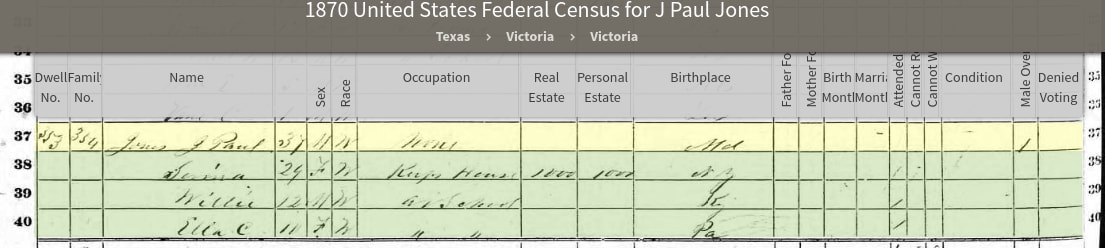

Since that 1838 Estate List is the only evidence of any Fanny I could find in the papers, I turned back to her 1867 letter. She lived in Texana, in Jackson County, Texas, and referenced J. Paul Jones, a literate man who was writing for her. I decided to look for a Fanny from Texana in the 1870 U.S. Census, using the library’s subscription to Ancestry.com. One problem I faced was the location, Texana, which is not referenced in the 1870 Census (too small, I suppose) and is now a ghost town under the Lake Texana Reservoir. I ended up using J. Paul Jones as a reference point. By 1870, he was living in Victoria, Texas, near enough to Jackson County for me to feel confident that it was him.

He was a relatively successful landowner originally from Maryland. I then narrowed the search with a birthplace of North Carolina and a race of Black or Mulatto. And I eliminated the Fannys who were too young in 1870 to have had children before 1865.

He was a relatively successful landowner originally from Maryland. I then narrowed the search with a birthplace of North Carolina and a race of Black or Mulatto. And I eliminated the Fannys who were too young in 1870 to have had children before 1865.

I ended up with two possible Fannys in Texas; but, neither matched the age of the Fanny on the Henry Slade estate inventory. The first, Fanny Ward, was 26 in 1870; her estimated birth year was 1844. At the time of the census she lived with Lucas Ward (30) and George Nicholson (62) in Matagorda County, Texas, near Jackson County. The letter mentions a George, which is why this Fanny seemed like a possibility. But I’m also thinking that Fanny Ward seemed too young to be referring to herself as an old woman in her letter to her sister. The other option in Texas was Fanny Oliver, from Victoria County, Texas, also near Jackson County. In 1870, Fanny Oliver was about 58 years old, and was married to John Oliver (62). The tone of the letter reads to me like an older adult woman; between these two Fannys, I was leaning toward Fanny Oliver.

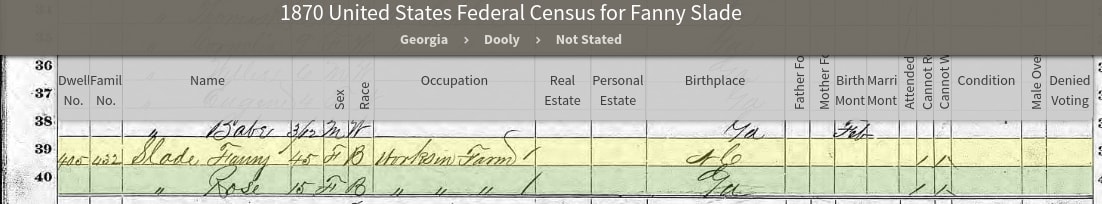

That of course presumed that Fanny still lived in Texas three years after she wrote her letter to Mr. Slade. I began to wonder if I had it wrong. Maybe by 1870, she had reconnected with her children and had returned to the East Coast. In looking around the 1870 census, I found several former Slade slaves who had taken the Slade name; I decided to see if there was a Fanny Slade living somewhere outside of Texas. It turns out yes, there were several Fanny Slades in 1870. I narrowed my census search to slaves born in North Carolina in or around 1820, and found the following:

Slade, Fanny. 45. F. Black. Works on Farm. Birthplace: NC. Cannot Read. Cannot Write.

Slade, Fanny. 45. F. Black. Works on Farm. Birthplace: NC. Cannot Read. Cannot Write.

And with her: Slade, Rose. 15. F. Black. Works on Farm. Birthplace: GA. Cannot Read. Cannot Write.

Circumstantial evidence suggests this is the right Fanny. She adopted the Slade last name. In 1870 she was 45, meaning that in 1867 she was 42 — she was old enough to have children pre-war. She would have been born around 1825, only 2 years off from the 1838 estate valuation from the Slade Family Papers, which put Fanny’s birth year as 1823. In 1870, Fanny Slade was living in Dooly County, Georgia, which was home to numerous other Slades, both black and white, in the 1870 Census. And most gratifying, in my mind, was to see that in 1870 she was living with Rose, a daughter, which suggests that her quest to be reunited with her children was partially successful.

It could be that I’m totally wrong; the Slade Family Papers are frustratingly silent and I’m out of ideas as to how to cross-reference this hypothesis. Too many blanks in the evidence means I have too many unanswered questions, the first being, What Happened to Fanny’s Other Children? I doubt we’ll ever know.

Letters from former slaves to their masters, like Fanny’s, are extraordinary documentary evidence of freedmen and women claiming their freedom and their rights. What’s amazing to me is that this letter was not only written, but has survived. So many former slaves did not have Fanny’s resources, especially friends like J. Paul Jones, to help her find her children. I hope that she at least found some answers, even if I never do.