Post contributed by Brooke Guthrie, Research Services Librarian.

You may have noticed (and we really hope that you have) that campus life is a bit different in Fall 2020. We’re all wearing masks, washing our hands, and obsessively monitoring our symptoms. We’ve also spent at least a few minutes speculating on the many unknowns—including the possibility of a coronavirus vaccine and how it might be distributed to the Duke community. The Duke Compact asks students, staff, and faculty to pledge to “Get the flu shot and other required vaccinations by designated deadlines.” And that made us wonder about the history of vaccinations at Duke.

You can learn a lot about Duke history from the Duke Chronicle and its predecessor, the Trinity Chronicle. Luckily for us, issues of the newspaper from 1905 to 2000 have been digitized by Duke University Libraries and can be fairly easily searched. Searching the newspaper reveals that campus-wide vaccination efforts are nothing new to Duke. Here are a few of the examples we found.

We’ll start by going way, way back to a time before Duke was called Duke. In 1914, during the Trinity College days, a vaccine against typhoid fever was offered to students, faculty, and their families. In addition to announcing the availability of the vaccine, the Trinity Chronicle published information on the effectiveness and safety of the vaccine as well as the number of deaths caused by typhoid in the state (about 1,200 each year). The article ends by noting that the administration “is anxious to see a large number of students avail themselves of the opportunity to obtain immunity from typhoid.”

A little over a decade later, in 1928, students were asked to get a smallpox vaccine. The very short announcement suggests that vaccination is no big deal: “the nurse will give the vaccines in a few minutes, and it will all be over.” Although noting that there were no serious cases on campus, the article says that six students were confined and lists their names. (Reporting campus illnesses and including the names of the ill was a fairly common practice back then.)

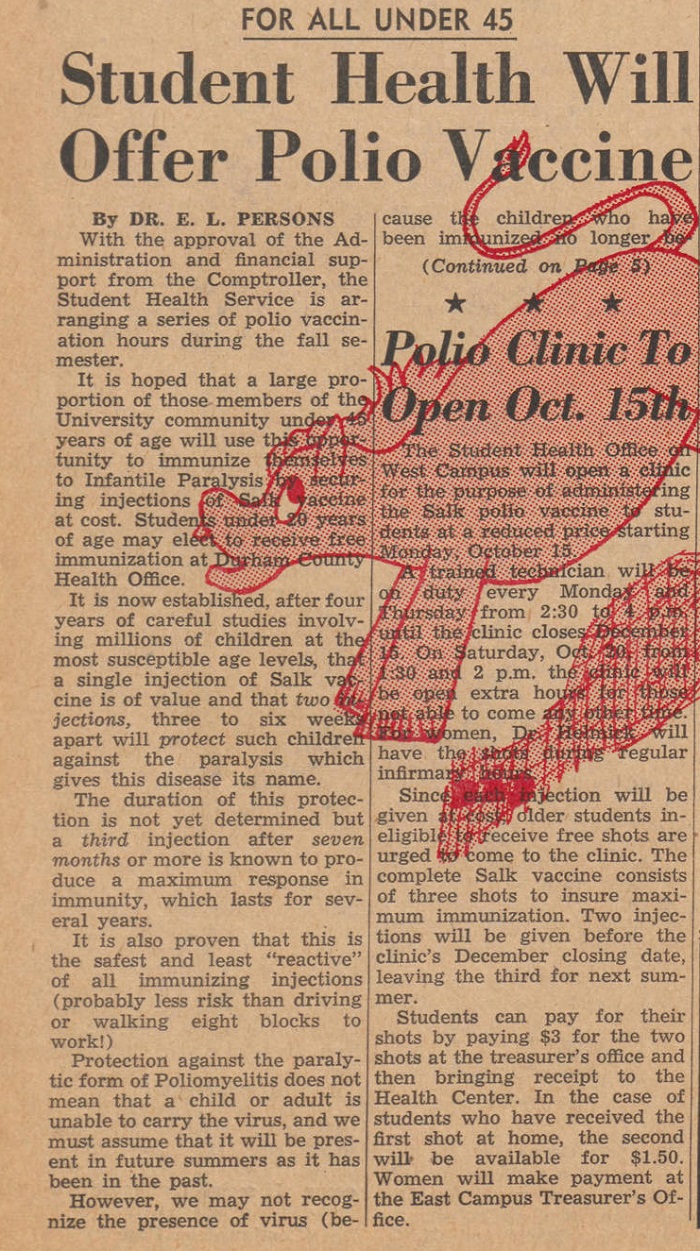

Polio was perhaps one of the most troubling diseases in the mid-twentieth century and the widespread concern was justified. In 1948, the worst year for polio in North Carolina, 2,516 cases and 143 deaths were reported in the state. In October of 1950, a Duke undergraduate named Daniel Rathbun died after contracting polio and spending two weeks in an iron lung at Duke Hospital. When a polio vaccine became available in 1955, vaccination campaigns were held throughout the country. In October of 1956, the Duke Chronicle announced that student health would offer the vaccine to all under 45 years old. For students, the vaccine cost $3.00. The article discusses what is known about the relatively new vaccine, emphasizes the importance of getting vaccinated, and notes that previously most college students were required to get vaccinated for typhoid fever (as if to say “why should this be any different?”).

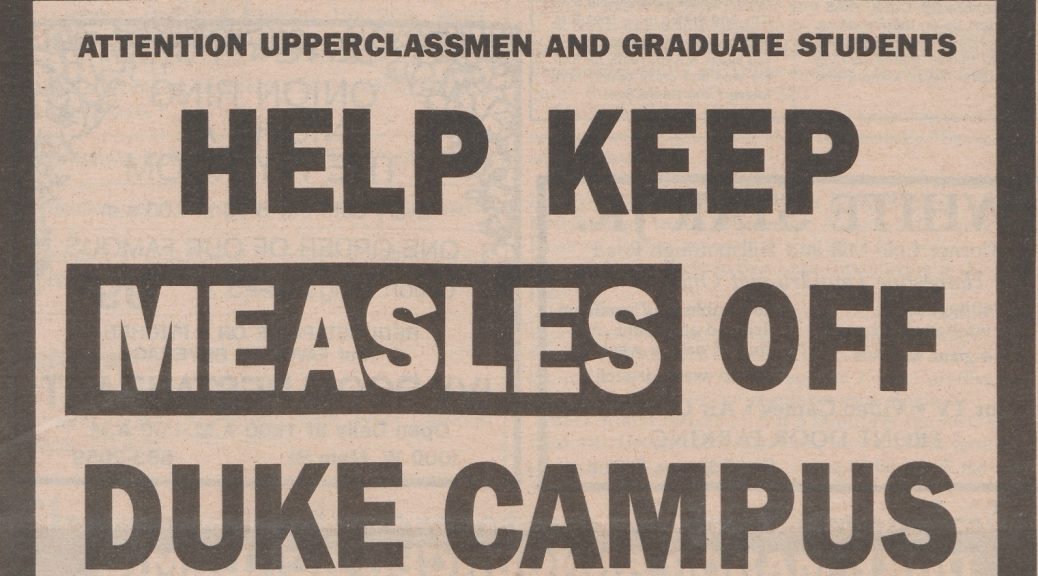

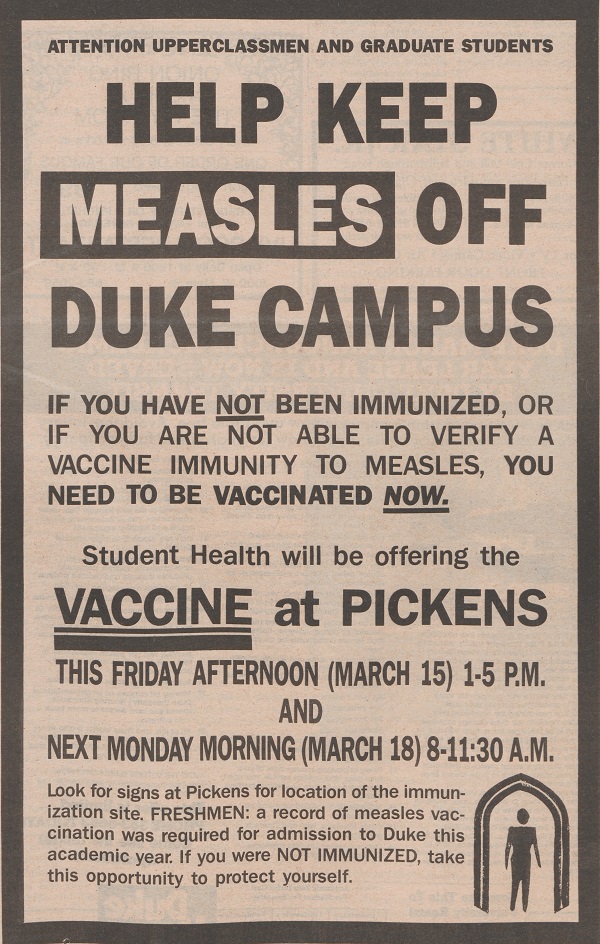

Efforts to vaccinate campus continued through the rest of the 20th century. In the mid-1970s, an outbreak of swine flu in the United States led to a nationwide vaccination drive. In November of 1976, Duke announced that it had 5,000 shots available to students and staff. In the 1980s, measles was a cause for concern on campus. In March 1985, the Chronicle published a large notice to let unvaccinated students know that “YOU NEED TO BE VACCINATED NOW.” A few years later in January 1989, a statewide outbreak spread to campus and Duke quickly “issued more stringent vaccination requirements” for both students and staff. Soon after Duke issued the new requirements, all unvaccinated students and staff were excluded from campus for two weeks. Staff were told to stay home. Students were barred from campus housing and had their Duke cards deactivated.

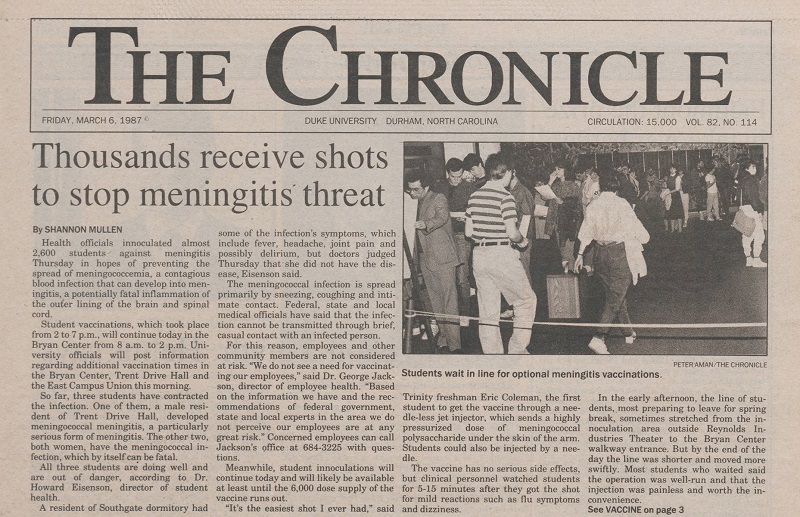

Concerns around meningitis in 1987 brought similar calls for large scale vaccination after a small number of students were infected. The Chronicle reported that mandatory vaccination was possible and, in March of 1987, thousands of students received a vaccine in a single day as part of the administration’s goal to distribute 6,000 doses.

There are many other examples of vaccination efforts in Duke’s history—the campus-wide distribution of the annual flu vaccine is one we’re all familiar with and, in 1999, students were encouraged to get a hepatitis B vaccine with a hip Chronicle advertisement that said “Hepatitis B is a very uncool thing” and the vaccine will keep you from “turning an embarrassing shade of yellow.”

If you’re interested in exploring this history more, try searching digitized issues of the Duke Chronicle or get in touch with our helpful staff. And, while we have your attention, make sure to get your flu vaccine this year!