Post contributed by Jennifer Dai, Josiah Charles Trent History of Medicine Intern.

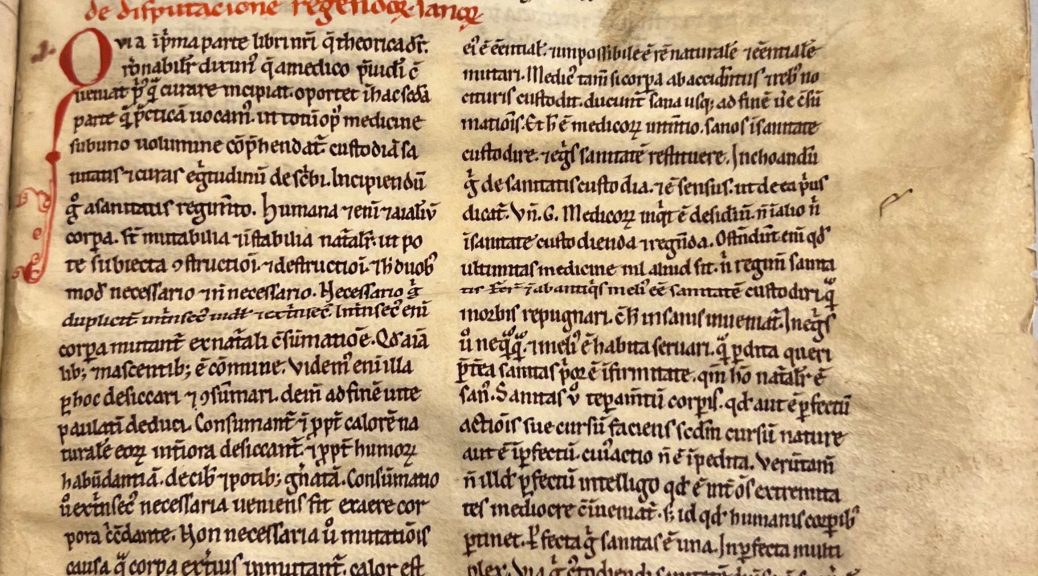

As I near the end of my first semester as the Josiah Charles Trent History of Medicine Intern at the Rubenstein Special Collections Library, I’ve started reflecting on some of the amazing materials I’ve had the opportunity to work with. From Vesalius to the Four Seasons, I’ve handled exquisite and priceless items, often becoming caught up in their splendor and rarity. In those moments, I’ve found it easy to forget the human side of medicine. I look at hand-colored drawings and notice the artistry and the time it took to create such pieces but forget that the depictions are often of actual events that happened to real people.

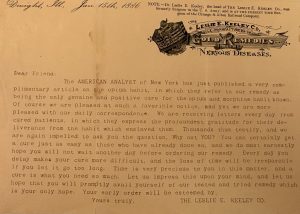

I’ve spent the past few months researching patent medicine (aka quack medicine). Its colorful advertisements, deadly undisclosed chemicals, statistics, and fun facts are flashy and interesting. But they distract from the humanity of medicine. How did these cure-alls truly affect those who were on the receiving end of these treatments? How and why were they used? This is where the story of William Anderson Roberts comes in.

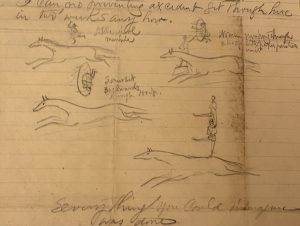

The William Anderson Roberts Papers start in the 1850s with a young William corresponding with friends and family about his faith, work as a portrait painter, and love life. By August 1859, letters that used to be addressed “Dear Brother” are now addressed “Dear Brother and Sister”, implying he has married (which he did, to a woman named Mary earlier that year). In 1861, William enlists in the Confederate Army and, throughout the war, is consistently in and out of the hospital. Despite numerous letters and attempts to be discharged due to a chronic medical condition called Neuralgia, he remains in the army until the end of war in 1865.

This lifelong affliction led to William’s first prescription for opium. He states that it not only “relieved the dreadful pain, but it soothed and quieted my irritable nervous system and stimulated my mind to act with double strength and quickness.” Later in his writing, he claims he could have stopped the habit if it hadn’t been for the “Cruel War.”

During the “Cruel War” in 1864, a doctor prescribed opium to help with ongoing diarrhea and dysentery after William had a bad case of measles. This treatment continued for weeks, and when he tried to stop, he found that he could not complete his assigned duties. He tried for years to overcome his dependence but was unable to paint or function without taking morphine.

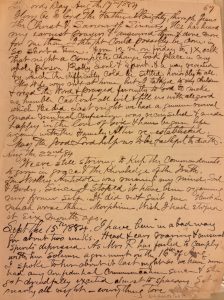

William never overcame the addiction. By the 1880s the effect of continued opiate use is apparent in his correspondence. Where he had previously been requesting assistance from patent medicines, he now practically begs for cures. He states that his wife doesn’t understand him and has never even tried and goes as far as to say she would be better off if he were no longer alive. He mourns the life he could have had and discusses his guilt over not being a healthy and happy husband and father.

Fittingly, the last item attributed to him, and how his date of death is estimated, is a receipt for morphine dated between June and September 1900. Based on this estimate, he died at 63 years old.

William’s story isn’t particularly unique. Many people then became addicted to opium after taking the medicine under a doctor’s orders. Many people still do.

What is remarkable about this collection is that we have access to his letters over 150 years after they were received. This collection, and those like it, give us the chance to see the humanity in individuals from over 100 years ago. To understand a person’s struggle and see firsthand the effects it has on them is something deeply intimate. Looking beyond the titles or rarity of items, you may just find the humanity of someone you will never meet.