Post contributed by Will Clemmons, Duke Family Processing & Digitization Intern.

When I visited Duke in 2018 with my family, this time to give my younger brother the opportunity to explore the possibilities of life at a top university, I never imagined that I would end up being the one in my family to play a part in this university’s history. Tar Heel basketball has always had my family’s support, but we never disrespected Duke. At the time of the tour, I was trying my best to avoid going on the traditional college route myself, and I certainly was not envisioning a future where I would be pursuing a master’s degree as a Tar Heel. But our best laid plans do not always work out in the way we envision them, often leading to paths far greater than we could imagine. I thus found myself in the summer of 2023 moving to UNC Chapel Hill to pursue a master’s degree in library science, with an emphasis in archiving, pursuing goals I never dreamed were possible.

I knew going into this Duke internship that I would enjoy the job of a processing archivist, but I did not know just how specialized the position was, as the Duke Family Processing & Digitization Intern. My past archival internships/volunteer work had been at smaller institutions that often had a solo archivist. Working with such a small staff meant the hats my bosses would wear, and would pass on to me, spanned the breadth of jobs an archivist can perform, from accessioning to processing, digitizing to describing. At Duke, I was tasked with only processing collections in the fall with Rubenstein Technical Services and digitizing collections in the spring, both tasks I had done before, but not at the level of specialization and detail that was allowed by the Rubenstein Library’s large size. During the fall semester I was essentially doing the job that any full-time processing archivist would do, just as an apprentice, so to speak, under Zachary Tumlin’s tutelage. Tumlin, the Duke Family Papers Project Archivist, was tasked with processing the many additions from Mary Duke Biddle Trent Semans to her collection of family papers at Duke University, and I was hired to assist him. Our job was to establish physical and intellectual control of the donated materials and arrange, rehouse, and describe them for use by others. In the short term, we prepared a number of these objects for the digitization I would do at the Digital Production Center (DPC) in the Spring semester. Through this work I learned more than most about the Duke family, Mary Semans in particular, and her many children and grandchildren.

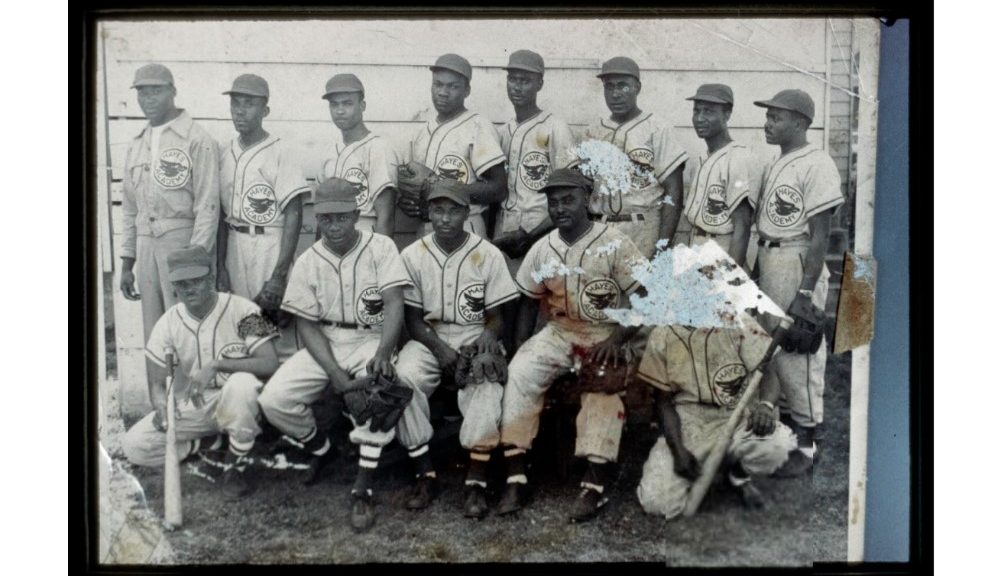

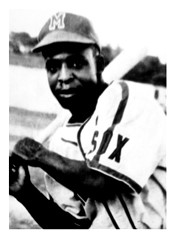

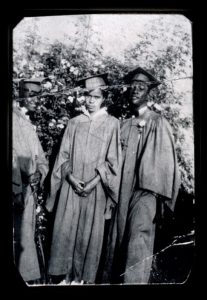

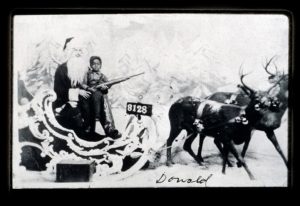

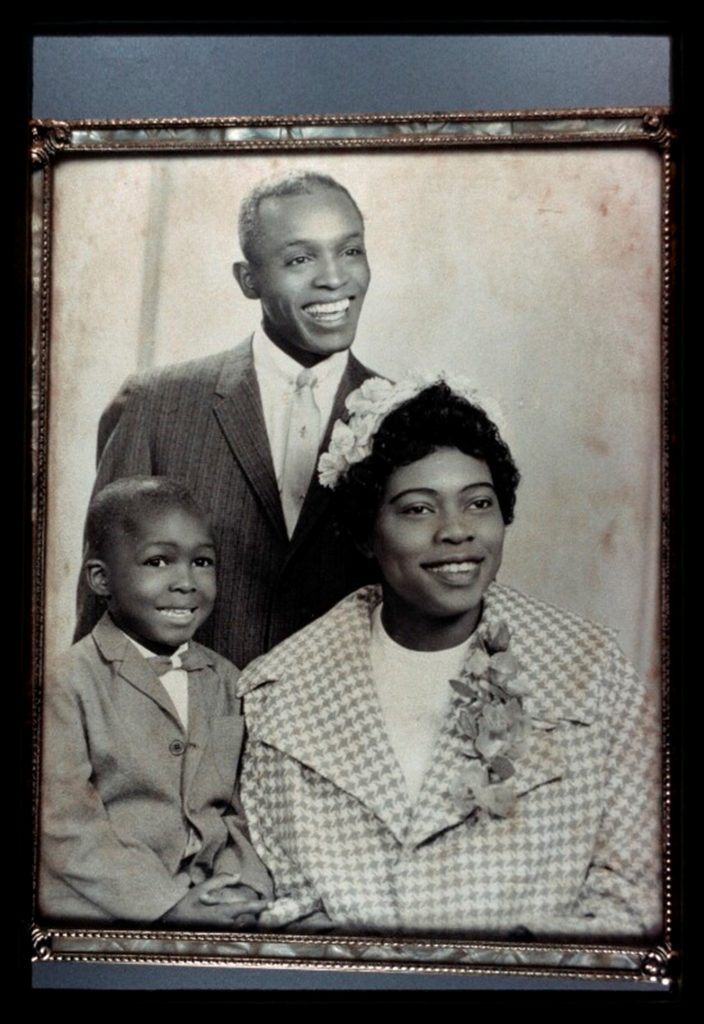

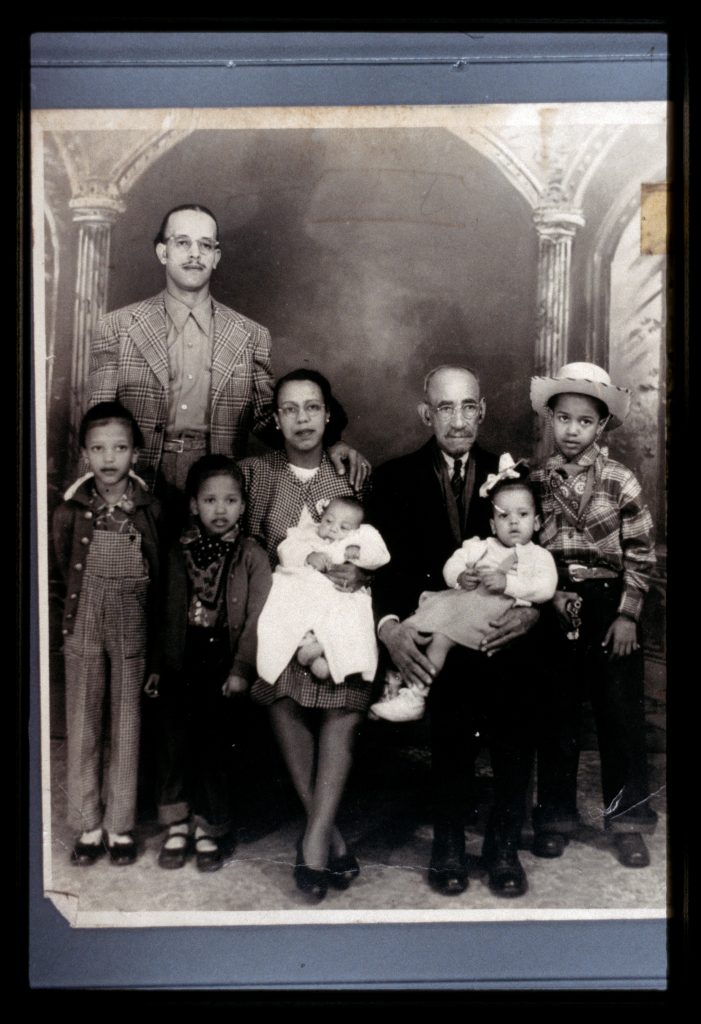

What makes Mary Semans’ donations so special are her ties to the founding Dukes. Being one of the last living Dukes to have known Benjamin Newton Duke, her maternal grandfather, Mary Semans had a wealth of Duke family history from Benjamin Duke to donate to the Rubenstein Library. For this reason, I was able to interact with objects with date ranges from the late 19th century up to the 2010s, specifically a large variety of photographic formats. Before working at Duke, I had never interacted with a tintype, one of the earliest democratic photography formats (meaning widely available to the public) that, while involving metals in photo processing, ironically tended to use metals other than tin. I was taught about the preservation of tintypes from talking with staff the Conservation Department, also learning how to keep them stored for long term preservation. The education I received through interacting hands-on with items that spanned such a broad period of history is a rare opportunity and will undoubtedly serve me well in my future archival endeavors.

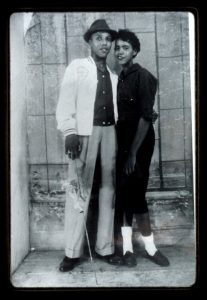

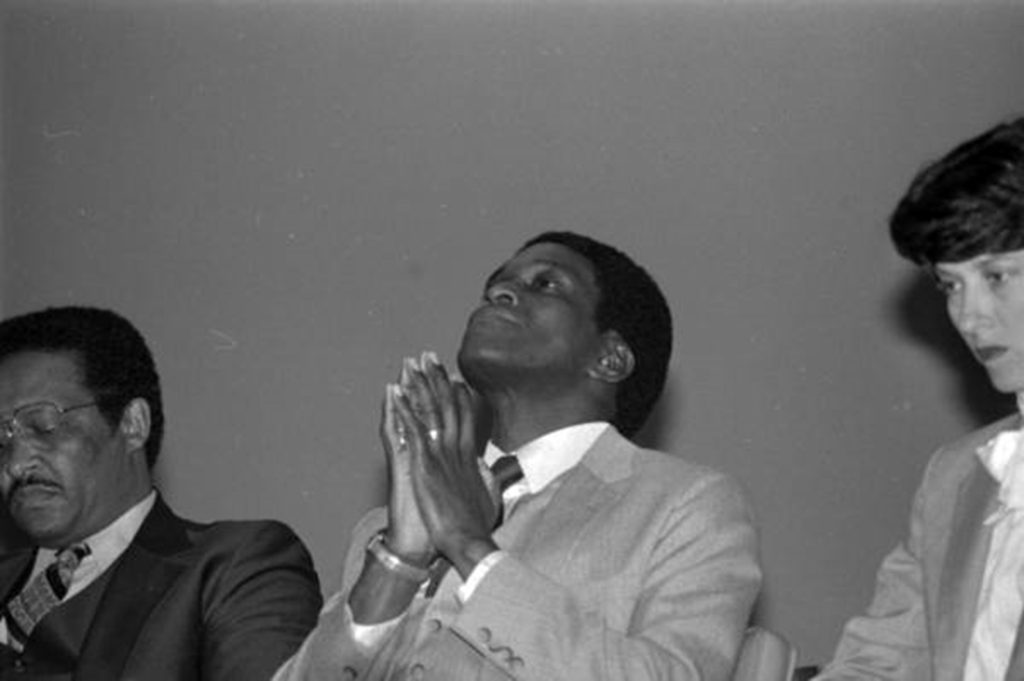

Learning about Mary Semans as a person would be sure to leave an impact on anyone. This heir to Benjamin Duke’s wealth did more than most with the wealth she was born into. As a philanthropist, she supported the university that bears her family’s name (with Duke being named after her great Grandfather) and the city in which it is situated. She did much to advocate for the people of NC nationally and internationally, earning the nickname “the unofficial First Lady of NC.” Her support for the arts, medicine, the disabled, and civil rights throughout her life is laudable. She was not unacquainted with grief, with her parents divorcing when she was around 10 years old and losing her first husband, with whom she had four children, at the young age of 28. Yet, she did not let this grief define her, marrying again, raising a total of seven children, and remaining vigorously invested in public life in Durham and NC until her death in 2012. I recall looking through numerous folders of photographs from trips to Europe in the 1990s that were not just sightseeing tours. Each trip was connected to the North Carolina School of the Arts’ International Music Program, designed to introduce students to the life of a touring musician while promoting North Carolina internationally. Even while traveling abroad, Mary Semans was committed to supporting the residents and the state of North Carolina.

The people in Duke Libraries who worked around me, and directly with me, imparted knowledge to me that will benefit me throughout my career. The team cohesion at the Digital Production Center (DPC) was evident from my first day this spring. Everyone in the DPC is dedicated to seeing their work reach maximum potential in efficiency and quality, utilizing the best in cultural heritage digitization processes. My work at the DPC saw me scanning artifacts from the Rubenstein Library’s collections, creating faithful digital surrogates for online teaching, learning, and research. In particular, I was able to work with courtship letters from 1935-1938 between Mary Semans and her first husband (Joe Trent), from processing in the Fall through to their digital existence with my work at the DPC. I felt very much at ease working at the DPC, knowing I had experts surrounding me that were eager to share their knowledge and ensure I had a successful internship. I could go on recognizing the talented individuals working in the DPC, but this is meant to be a relatively short blog post, so I will refrain for now.

I leave Duke University Libraries, more confident than ever in my abilities to enter the job market with the skills necessary to land me a full-time job in archiving. Duke has also left me with a stronger conviction that archiving is what I want to spend my career pursuing. I hope the reader understands the dedication of the Rubenstein Library’s staff and takes the time to browse their collections, many online (Duke Family Papers), perhaps in the process learning some about the founding family at Duke University and their significant contributions to the Durham area.