Post contributed by Michael Ortiz-Castro, PhD, Lecturer, Department of History, Bentley University. Micheal was a recipient of the John Hope Franklin Research Center Travel Grant & Elon Clark History of Medicine Travel Grant.

Life insurance seems, perhaps, like one of the duller aspects of adulthood. For late 19th century Americans, life insurance represented and marshalled a number of concerns and anxieties about value, life, and community. Coming to force in the mid to late 1800s, life insurance—acquiring it, maintaining it, using it, and its meaning—all intertwined with questions about race, nation, and community—not surprising given that life insurance dealt with some of the most intimate aspects of individuals’ lives—their health, the health of their families, and the economic and social wellbeing.

As a historian of citizenship, my research discusses the history of life insurance as part of a broader analysis of the transformation of ideas of citizenship in the wake of the civil war. My book project, presently titled Acts of Citizenship: Belonging and Biology in Post-Reconstruction America, discusses life insurance in the context of the language companies used to sell policies to Americans, how folks in and outside the industry discussed the business of calculating the value of human lives, and the industry’s associated practices. These practices had a vision of citizenship yoked to ideas of biology and racial purity and helped shape the culture of life insurance—which would come to center round keywords like race, family, and citizen. At its intellectual heart was a project of racial differentiation, materialized in Irving Hoffman’s “Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro”. Written in his capacity as Statistician for the Prudential Life Insurance Company, the tract used mortality rates to not only advocate for denying insurance policies to black Americans, but to popularize the “extinction thesis”, a theory that black Americans were simply biologically unfit for equality.

What did black Americans make of this evolving discourse? With the generous support of the History of Medicine Collections and the John Hope Franklin Research Center at the Rubenstein Library, I began to answer this question by consulting the records of the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company, the largest black-owned life insurance company in the nation. Their records highlight the complicated place of black life insurance companies in the economic landscape; they highlight the complicated ways in which black Americans sought to both prove their fitness for citizenship and resist the terms that condemned death to permanent exclusion.

**

Black life insurance companies like North Carolina Mutual grew in a lacuna. The first black insurance companies came up to help black Americans cover funeral costs; North Carolina Mutual marketed itself as a life-oriented project; like other life insurance companies, the stated goal of North Carolina Mutual was to “help Negroes … accumulate … a fortune in life”, to make burial insurance unnecessary. Though life insurance companies faced significant headwinds in their early days due to the perceived sacrilege of putting a value to human life, they participated in and benefitted from a cultural transformation that saw it worthwhile to invest in one’s own life.

North Carolina Mutual’s insistence that black lives could yield value for the user was complicated for two reasons. The first reason was that, according to white insurers, black lives were too risky to include in the risk pool—better to keep them out, for no value or benefit could be generated for the community. In constructing their own risk pool, North Carolina Mutual posited a different vision of the community. However, the notion that black lives could yield value for their owner drew eerie parallels to the slave insurance policies of the antebellum era—it had been commonplace for owners to ensure the lives of their slaves and receive payment in the case of death. In attempting to both affirm and challenge the prevailing association between value, appreciation, and race, North Carolina Mutual affirmed that black lives were appreciable assets—and could be a boon when that wealth was owned by the individual themselves. This logic seems to have been a motivating factor for other black-owned business companies—for example, as seen below, the Atlanta Life Insurance Company similarly sold its mission as “a dream to develop economic independence” among black Americans.

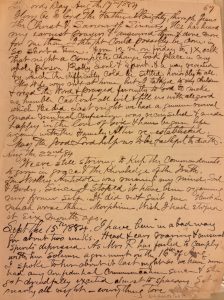

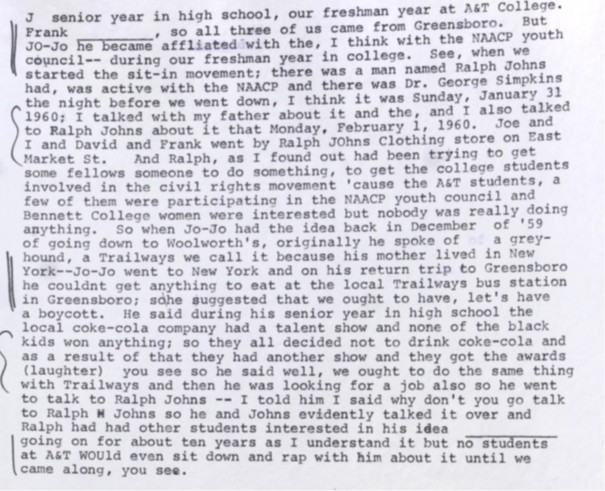

North Carolina Mutual insisted on more than just that black lives could be considered appreciable assets. At the heart of their industry was the assumption that black lives were insurable to begin with—that is to say, a good risk. To do so, it had to assert that black lives were not, say, any riskier than white customers. One bulletin from Clyde Donnell, the Medical Director, makes the logic clear. An excerpt of the document, which discussed tuberculosis mortality rates among black Americans, can be seen below. Below that, you can see another piece, also written by Donnell, which discusses the issue of finding enough black Americans to ensure.

The doctor’s argument in both documents once more ambivalently positions black American’s health to that of their white counterparts. White insurance executives, like Hoffman, argued that high mortality rates across diseases between black and white Americans was indicative of innate biological inferiority. Black intellectuals like W.E.B. DuBois often tried to argue that these disparities were the result of racist measurements and biases; in his magisterial The Health and Physique of the Negro American, DuBois used modern sociological methods to prove that, in aggregate, mortality rates were consistent across race according to class. This was not the strategy of North Carolina Mutual—they affirmed the notion that black folks did in fact have higher mortality rates. However, rather than cast these higher mortality rates as evidence of biological inferiority, Dr. Donnell instead asserts that this means that white folk should become more invested in the uplift of black Americans—“the negro means much to the economic welfare of the southern white man”. In the latter, Donnell references the environmental factors DuBois preferred while maintaining the fact of disparate health outcomes according to race. In tying their destinies together, Donnell’s logic resisted the idea that a white America was the inevitable result.

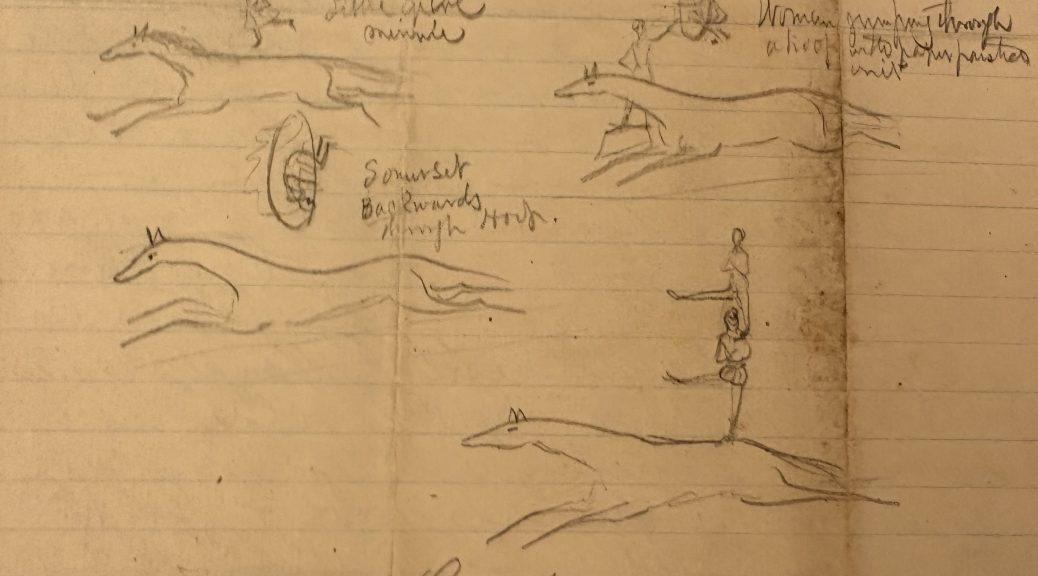

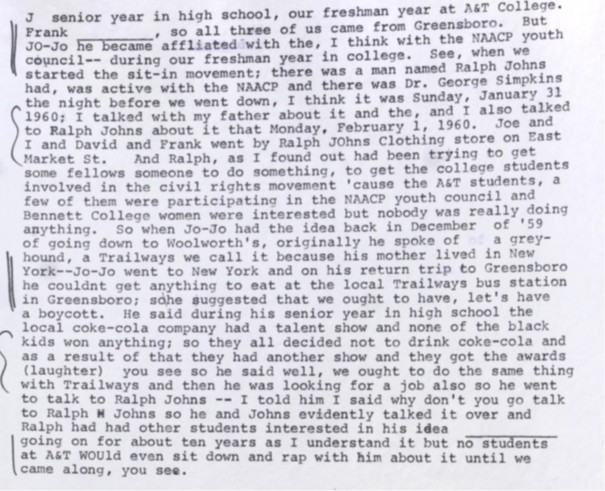

As materially important as it was for black Americans to have access to life insurance and the financial means to support themselves through death and emergencies, like other life insurance companies, North Carolina Mutual understood that its project was not just about securing the financial wellness of its members—no, the goal was to secure the political and economic uplifting of the people

This can be seen below, where the writings double as political mission: “it is better not to have lived, than to have lived and not contributed anything to the success of any one else’s life”.

At the time of its founding, North Carolina Mutual found itself serving a community that had achieved massive cultural victories alongside the entrenchment of Jim Crow in the South. As a business that believed in racial uplift, it relied on the language of progress and assimilation evinced by leading intellectuals by Booker T Washington. However, as a business oriented towards the advancement of black Americans in the face of racism, it had to take a stand on discourses of racial inferiority. Life insurance singularly combined questions of individual health and the future of the community that animated many of the driving cultural transformations of the late 19th century—the records of NC Mutual prove useful in understanding how black Americans navigated their place in the nation, and how the fight for equality extended to the domain of health, wellness, and the everyday.